Alarming new "superbug" gene found in animals and people in China

A new gene that makes bacteria highly resistant to a last-resort class of antibiotics has been found in people and pigs in China - including in samples of bacteria with epidemic potential, researchers said on Wednesday.

The discovery was described as "alarming" by scientists, who called for urgent restrictions on the use of polymyxins - a class of antibiotics that includes the drug colistin and is widely used in livestock farming.

"All use of polymyxins must be minimised as soon as possible and all unnecessary use stopped," said Laura Piddock, a professor of microbiology at Britain's Birmingham University who was asked to comment on the finding.

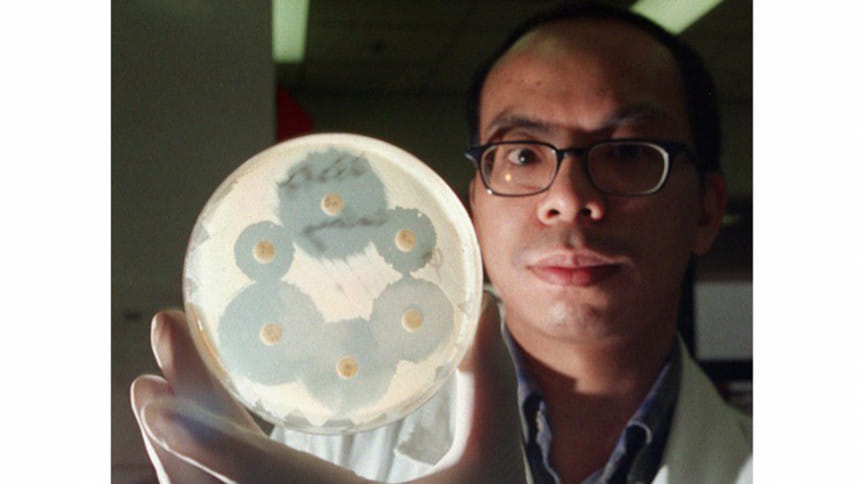

Researchers led by Hua Liu from the South China Agricultural University who published their work in the Lancet Infectious Diseases journal found the gene, called mcr-1, on plasmids - mobile DNA that can be easily copied and transferred between different bacteria.

This suggests "an alarming potential" for it to spread and diversify between bacterial populations, they said.

The team already has evidence of the gene being transferred between common bacteria such as E.coli, which causes urinary tract and many other types of infection, and Klesbsiella pneumoniae, which causes pneumonia and other infections.

This suggests "the progression from extensive drug resistance to pandrug resistance is inevitable," they said.

"(And) although currently confined to China, mcr-1 is likely to emulate other resistance genes ... and spread worldwide."

Indian Precedent

The discovery of the spreading mcr-1 resistance gene echoes news from 2010 of another so-called "superbug" gene, NDM-1, which emerged in India and rapidly spread around the world.

Piddock and others said global surveillance for mcr-1 resistance is now essential to try to prevent the spread of polymyxin-resistant bacteria.

China is one of the world's largest users and producers of colistin for agriculture and veterinary use.

Worldwide demand for the antibiotic in agriculture is expected to reach almost 12,000 tonnes per year by the end of 2015, rising to 16,500 tonnes by 2021, according to a 2015 report by the QYResearch Medical Research Centre.

In Europe, 80 percent of polymixin sales - mainly colistin - are in Spain, Germany and Italy, according to the European Medicines Agency's Surveillance of Veterinary Antimicrobial Consumption (ESVAC) report.

For the China study, researchers collected bacteria samples from pigs at slaughter across four provinces, and from pork and chicken sold in 30 open markets and 27 supermarkets in Guangzhou between 2011 and 2014. They also analysed bacteria from patients with infections at two hospitals in Guangdong and Zhejiang.

They found a high prevalence of the mcr-1 gene in E coli samples from animals and raw meat. Worryingly, the proportion of positive samples increased from year to year, they said, and mcr-1 was also found in 16 E.coli and K.pneumoniae samples from 1,322 hospitalised patients.

David Paterson and Patrick Harris from Australia's University of Queensland, writing a commentary in the same journal, said the links between agricultural use of colistin, colistin resistance in slaughtered animals, colistin resistance in food, and colistin resistance in humans were now complete.

"One of the few solutions to uncoupling these connections is limitation or cessation of colistin use in agriculture," they said. "Failure to do so will create a public health problem of major dimensions.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments