Ancient reptile with 'extremely long neck' unearthed in Alaska

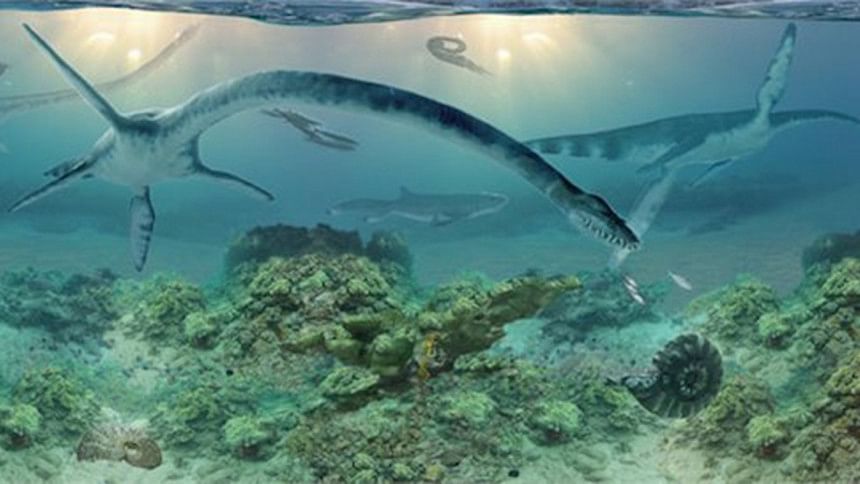

The fossilized remains of an ancient marine reptile with an extremely long neck and paddlelike appendages were recently uncovered in an unlikely place: the side of a cliff in Alaska, reports LiveScience.com.

LiveScience.com reports, the bones belong to an elasmosaur, an animal that swam the seas about 75 million years ago during the Late Cretaceous period, said Patrick Druckenmiller, earth sciences curator at the University of Alaska Museum of the North.

It's the first time that the skeleton of one of these creatures has been found in the state, he added.

"This is a very unusual group of marine reptiles that belongs to a larger group known as plesiosaurs, Druckenmiller told Live Science."Elasmosaurs are famous because they have these ridiculously long necks and relatively small skulls."

Most of the newly uncovered elasmosaur's bones are still lodged in a rocky cliff in the Talkeetna Mountains of southern Alaska, so no one has measured the full skeleton yet. But Druckenmiller, who visited the fossil site in June, estimates that the animal was about 25 feet (7.6 meters) long, with a neck that made up half its body length.

The incredible length of the ancient carnivore's neck gave rise to an interesting theory in the 1930s, when someone suggested that the mythical Loch Ness monster was really just a plesiosaur (possibly an elasmosaur) that didn't go extinct with the rest of its species. But Druckenmiller said that theory is a "bunch of bunk," because there's no way a plesiosaur could have held its head up out of the water like a swan (which is how "Nessie" commonly appears in popular culture and hoax photographs).

It is true, however, that plesiosaurs can sometimes end up in unusual places. The newly discovered Alaskan elasmosaur was found amid a mountain range that boasts peaks that are nearly 9,000 feet (2,743 m) high. That's a long way from the seafloor, which is where the remains of any elasmosaur would have likely settled after it died. So how did the bones find their way up the mountain?

"The rocks that the skeleton was found in were laid down on the seabed about 70 to 75 million years ago. At that time there was a sea along the southern margin of [what is now] Alaska," said Druckenmiller, who added that over the course of many millions of years, tectonic activity under that ancient sea caused the seafloor to rise up thousands of feet.

The rocky cliffs of the Talkeetna Mountains boast many fossils that hint at this aquatic past. However, most of the fossils found there belong to invertebrates, not marine vertebrates, Druckenmiller said. The fossilized remains most commonly found in the range belong to ammonites, an extinct group of marine animals that he said look like "overgrown nautilus" (mollusks with hard, spiral shells).

Finding the remains of a vertebrate, especially one as large and intact as the elasmosaur, is a real treat for Druckenmiller, who noted that similar fossils have been found in Canada and in the continental United States, but only in places like Kansas, the Dakotas and Montana, where rocky, barren terrain is better-suited for fossil hunting. (The presence of marine animal fossils in those states has to do with the fact that, millions of years ago, central North America was submerged under a seaway that divided the continent into two landmasses.)

"These fossils are found in classic 'Badlands' environments in other parts of the world, with nice outcroppings of rock sticking out everywhere," Druckenmiller said. "In Alaska, there's a lot of vegetation, so it's hard to find good, accessible rock. Where we usually find it is pretty remote, mountainous areas where there's not a lot of vegetation because of the high elevation and the steep slopes."

And the vertical slopes of the soaring Talkeetna Mountains make the region a better place than many others in southern Alaska to look for fossils. It's not the first time an ancient skeleton has been discovered there. In 1994, workers digging a quarry in the Talkeetna range unearthed the partial remains of a plant-eating ornithopod dinosaur (a close relative of duck-billed dinosaurs) that had floated out to sea and finally came to rest on the seabed, which later rose up to form the massive mountains.

That hadrosaur, nicknamed "Lizzie," is on display at the Museum of the North (where Druckenmiller works) in Fairbanks, Alaska. It's not yet clear where the elasmosaur skeleton will end up once it's completely unearthed, but Druckenmiller said he's glad the ancient remains are close enough to visit.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments