Declassified: US Military's secret Cold War space project revealed

A newly released treasure trove of historical data reveals intriguing details about a secret Cold War project known as the Manned Orbiting Laboratory (MOL), reports Space.com.

According to Space.com the US Air Force's MOL program ran from December 1963 until its cancellation in June 1969. The program spent $1.56 billion during that time, according to some estimates.

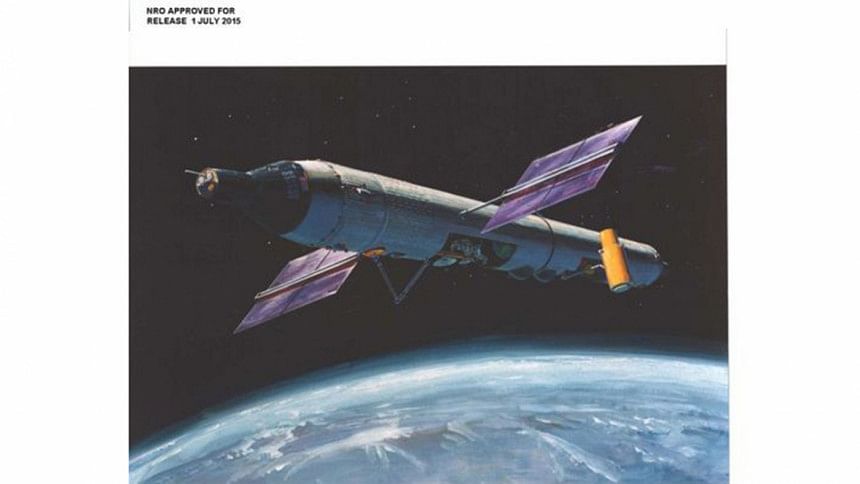

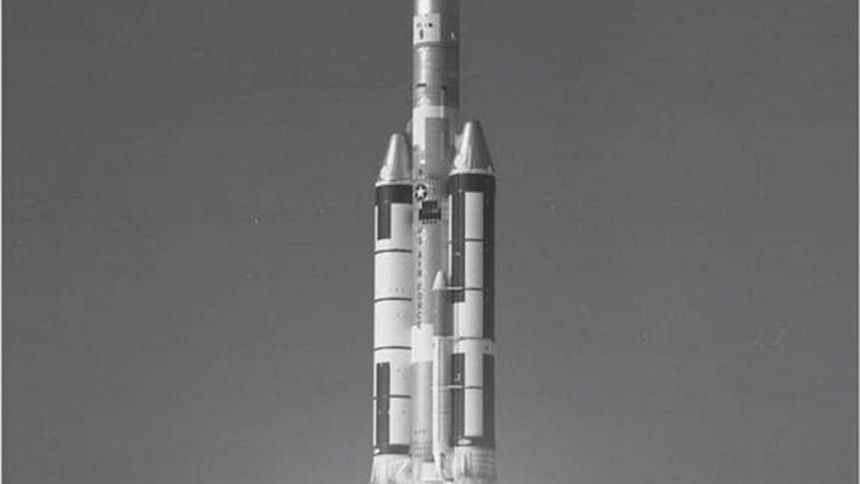

While the program never actually lofted a crewed space station, those nearly six years were quite eventful, featuring the selection of 17 MOL astronauts, the remodeling of NASA's two-seat Gemini spacecraft, the development of the Titan-3C launch vehicle and the building of an MOL launch site at Vandenberg Air Force Base in California.

Early in the MOL program, its architects weren't quite sure what MOL was all about. "Is the MOL a laboratory?" reads one of the newly released documents, which were put out by the US National Reconnaissance Office (NRO). "Or is it an operational reconnaissance spacecraft? (Or a bomber?)"

Even today, aspects of the MOL initiative remain secret.

Superpowerful eye spy

The anticipated duties of MOL crews included reconnaissance activities under the code name Project Dorian. Dorian was a superpowerful camera system that could acquire photographic coverage of the Soviet Union and other locations with a resolution better than the best unmanned system at the time, the NRO's first-generation Gambit spacecraft, reports Space.com.

But the historical documents suggest numerous other jobs were on the MOL docket for deliberation, including the use of side-looking radar, the evaluation of electronic intelligence-gathering gear and the assembly and servicing of large structures in space.

Also discussed were the use of MOL-carrying "negation missiles" that would use non-nuclear warheads, the inspection of satellites, and the encapsulation and recovery of enemy spacecraft, which may have been accomplished using rocket-propelled net devices.

For a spacewalking MOL crewmember, a remote maneuvering unit was considered key for approaching and circumnavigating a target while the astronaut remained at a safe distance "to prevent harm from an active defense or booby-trapped target."

Notably, there was much reflection regarding the biological and psychological responses of MOL crewmembers in orbit for 30 days or more.

Rediscover and recover facts

The NRO's release of MOL information was timed for an event held Oct. 22 at the National Museum of the USAir Force, which is located at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base near Dayton, Ohio.

Would-be MOL crewmembers and other program officials took part in the event, which was called "The Dorian Files Revealed: The Manned Orbiting Laboratory Crew Members' Secret Mission in Space."

"Time often allows for facts to be distorted or forgotten," said James Outzen, chief of historical documentation and research at the Center for the Study of National Reconnaissance in Chantilly, Virginia. "But history allows the opportunity to rediscover and recover facts."

MOL was born in a Cold War environment in which it was difficult to learn what the United States' adversaries were up to, Outzen said.

Patricia Cameresi, chief of the NRO's Information Review and Release Group, said the declassification of more than 20,000 pages of MOL documents was no easy task.

"It took over a year to get all the stakeholders involved … to get them to agree to [the] declassification of additional material and then to do the actual line-by-line review," Cameresi said.

Behind the Iron Curtain

According to Space.com former MOL astronauts taking part in the Oct. 22 event included James Abrahamson, Karol Bobko, Albert Crews, Bob Crippen and Richard Truly. Michael Yarymovych, who served as technical director of the US Air Force MOL effort, also participated.

"We were doing something that was exciting and important," Yarymovych said. "We're going to also do something very important for national security. We are going to go look behind the Iron Curtain … defend the nation while doing the exciting things of manned spaceflight."

After the termination of MOL, Truly, Crippen and Bobko became NASA astronauts, with Truly eventually ascending to NASA administrator status. Abrahamson led NASA's space shuttle program in the early 1980s, then later headed President Ronald Reagan's Strategic Defense Initiative, dubbed the "Star Wars" program.

Memory lane

For the MOL astronauts, the Wright-Patterson museum event was a trip down memory lane.

"It got canceled on June 10, 1969, a date that will live in my memory for a long time, which was one of the low points in my life," Crippen said.

Truly said MOL "was not a trivial thing that we were working on." He thought the program had solved some complex problems before "black Tuesday," when delays, cost overruns and other factors brought the program to an end.

MOL, which would have zipped around Earth in a polar orbit, pioneered complex human interaction with an automated film camera system, Truly said. "It would have made it far better than it could be done strictly as an automated system," he said.

Humans in the loop

In the view of Abrahamson, who was also assigned the job of building a training simulator for utilizing the MOL camera system, putting humans in the loop was an added benefit.

The MOL film camera was going to be so precise, Abrahamson said, that it could have photographed Soviet airfields or snagged imagery of aircraft flight tests and the testing of specialized munitions.

But the field of view through the camera would have been akin to "looking down a soda straw," making human judgment important, Abrahamson said. The astronauts "were supposed to use judgment and training … and to say, 'Look here, not here; don't waste a pass here,'" he added.

Important legacy

In the end, the death of MOL provided Abrahamson a lesson he has applied to other programs. "If you can just get an empty can up there … do it. Because then, you can build on it," he said.

The strategy with the Congress, "not the technical challenge," was the biggest risk, Abrahamson said.

According to Outzen, the reconnaissance historian, "There is often a misplaced assumption that a canceled program has no important legacy. This should not be said of the Manned Orbiting Laboratory program."

The MOL program should be recognized "for its rich legacy in both civilian and national reconnaissance space histories," Outzen concluded.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments