'Dino-chicken’ created in lab

Chicks with dino-snouts? With a little molecular tinkering, for the first time scientists have created chicken embryos with broad,Velociraptor-like muzzles in the place of their beaks, reports the science daily Live Science.

The bizarrely developing chickens shed new light on how the bird beak evolved, scientists added.

The Age of Dinosaurs came to an end with a bang about 65 million years ago, due to an impact from a giant rock from space, which was probably about 6 miles (10 kilometers) across. However, not all of the dinosaurs went extinct because of this catastrophe — birds, or avian dinosaurs, are now found on every continent on Earth.

"There are between 10,000 and 20,000 species of birds alive today, at least twice as many as the total number of mammal species, and so in many ways it is still the Age of Dinosaurs," study lead author Bhart-Anjan Bhullar, a paleontologist and developmental biologist at Yale University, told Live Science.

Fossil discoveries have recently yielded great insights into how birds evolved from their reptilian ancestors, such as how feathers and flight emerged. Another key structure that sets birds apart from their dinosaurs ancestors is their beaks. Researchers suspect that beaks evolved to act like tweezers to give birds a kind of precision grip. The beaks help make up for the dinosaurs' grasping arms, which evolved into wings, giving them the ability to peck at food such as seeds and bugs.

"The beak is a crucial part of the avian feeding apparatus, and is the component of the avian skeleton that has perhaps diversified most extensively and most radically — consider flamingos, parrots, hawks, pelicans and hummingbirds, among others," Bhullar said in a statement. "Yet little work has been done on what exactly a beak is, anatomically, and how it got that way either evolutionarily or developmentally."

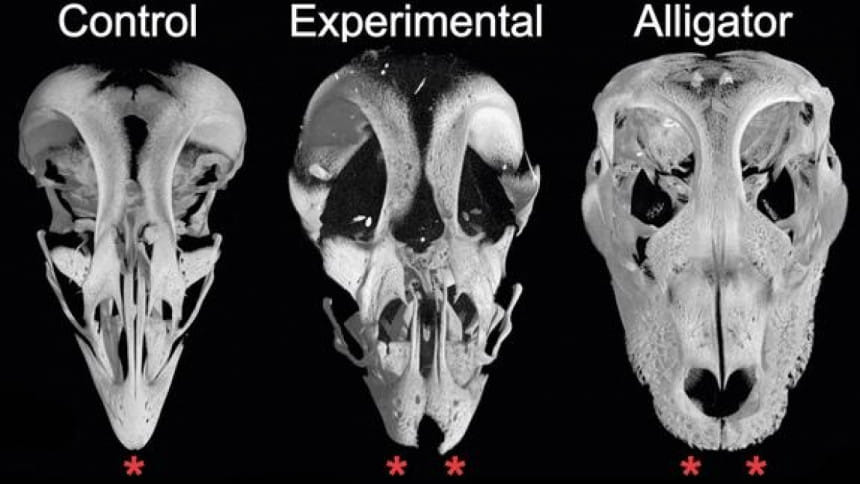

To learn more about how the beak evolved, a research team led by Bhullar and developmental biologist Arkhat Abzhanov at Harvard University have now successfully reverted the beaks of chicken embryos into snouts more similar to ones seen in Velociraptor and Archaeopteryx than in birds.

"The experimental animals did not have a beak, instead developing a broad, rounded snout," Bhullar said. However, "they still lacked teeth, and possessed a horny covering on the snout."

These embryos did not live to hatch, researchers stressed. "They could have," Bhullar said. "They actually probably wouldn't have done that badly if they did hatch. Mostly, though, we were interested in the evolution of the beak, and not in hatching a ‘dino-chicken’ just for the sake of it."

The researchers first analyzed the skeletons of modern birds, extinct birds, extinct dinosaurs and the closest modern reptilian relatives of birds. They analyzed the bones of embryos, juveniles and adult specimens to deduce how the anatomy of the ancestors of birds evolved the beak over time.

The bird beak developed from the premaxillae, which are a pair of small bones at the tip of the upper jaw in most animals. However, in birds, the premaxillae are enlarged and fused to form a beak.

The researchers next looked for genetic changes in birds that were linked with these anatomical changes. They analyzed genetic activity in the embryos of emus, alligators, lizards and turtles, with Bhullar sampling DNA from various animals, such as alligator nests in the Rockefeller Wildlife Refuge in southern Louisiana and an emu farm in western Massachusetts.

The researchers focused on two genes that help control the development of the middle of the face. The activity of these genes differed from that of reptiles early in embryonic development. They developed molecules that suppressed the activity of the proteins that these genes produced, which led to the embryos developing snouts that resembled their ancestral dinosaur state.

The researchers stressed that they are not yet capable of genetically modifying chickens to make then resemble their dinosaur ancestors. "We're not altering the genes themselves yet — we're altering the proteins that the genes produce," Bhullar said.

One intriguing implication of this research is that relatively simple genetic changes could have caused this anatomical change in the ancestors of birds, and that one might expect to see abrupt changes in anatomy in the fossil record. Bhullar said that such changes are seen in an extinct near relative of modern birds known as Hesperornis.

The strategy the research team followed to analyze the evolution of the beak could also help researchers study other major evolutionary transformations, such as the origin of mammals from their reptilian ancestors, Bhullar said. In the future, researchers could also investigate all the genes involved in the evolution and development of the beak, he added.

The scientists detailed their findings online May 12 in the journal Evolution.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments