See-through solar cells

Anyone who has sweltered in a south-facing office during the summer knows the power of solar energy streaming through a window.

In fact, no reputable urban architect today would design such a workspace without treated windows to reduce the sun's glare and heat.

But what if the window coating could do better than keep out the sun? What if that thin film could capture the solar energy for lighting the office, running the computers, and best of all, firing up the air conditioning?

That's the idea behind "transparent" solar, a technology that startup companies hope to bring to market soon, after at least two decades of U.S. government-backed and university research, reports National Geographic.

With the help of organic chemistry, transparent solar pioneers have set out to tackle one of solar energy's greatest frustrations.

Although the sun has by far the largest potential of any energy resource available to civilization, our ability to harness that power is limited.

Photovoltaic panels mounted on rooftops are at best 20 percent efficient at turning sunlight to electricity.

Research has boosted solar panel efficiency over time. But some scientists argue that to truly take advantage of the sun's power, we also need to expand the amount of real estate that can be outfitted with solar, by making cells that are nearly or entirely see-through.

"It's a whole new way of thinking about solar energy, because now you have a lot of potential surface area," says Miles Barr, chief executive and co-founder of Silicon Valley startup Ubiquitous Energy, a company spun off by researchers at Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Michigan State University.

"You can let your imagination run wild. We see this eventually going virtually everywhere."

Transparent solar is based on a fact about light that is taught in elementary school: The sun transmits energy in the form of invisible ultraviolet and infrared light, as well as visible light.

A solar cell that is engineered only to capture light from the invisible ends of the spectrum will allow all other light to pass through; in other words, it will appear transparent.

Organic chemistry is the secret to creating such material. Using just the simple building blocks of carbon, hydrogen, oxygen, and a few other elements found in all life on Earth, scientists since at least the early 1990s have been working on designing arrays of molecules that are able to transport electrons—in other words, to transmit electric current.

"The beauty of organic chemistry is there is a big variety of materials available," says Nikos Kopidakis, senior research scientist at the U.S. Department of Energy's National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) in Golden, Colorado.

"The sky's the limit. It can't be just anything, but we have a decent understanding of the requirements. You can design the material to look green to the eye, blue, any other color, or transparent."

Harvesting only the sun's invisible rays, however, means sacrificing efficiency. That's why Kopidakis says his team mainly focuses on creating opaque organic solar cells that also capture visible light, though they have worked on transparent solar with a small private company in Maryland called Solar Window Technologies that hopes to market the idea for buildings.

Ubiquitous Energy's team believes it has hit on an optimal formulation that builds on U.S. government-supported research published by the MIT scientists in 2011.

"There is generally a direct tradeoff between transparency and efficiency levels," says Barr. "With the approach we're taking, you can still get a significant amount of energy at high transparency levels."

Barr says that Ubiquitous is on track to achieve efficiency of more than 10 percent—less than silicon, but able to be installed more widely. "There are millions and millions of square meters of glass surfaces around us," says Barr.

Kopidakis notes that organic solar has another advantage over conventional silicon solar panels, which typically are manufactured by treating the silica in quartz sand in a high-temperature furnace. It requires far less energy to make organic solar coatings, and should cost far less once manufacturing is underway.

"You do not need an ultra-high-vacuum chamber, and you don't need to heat anything to 300 to 400 degrees," says Kopidakis.

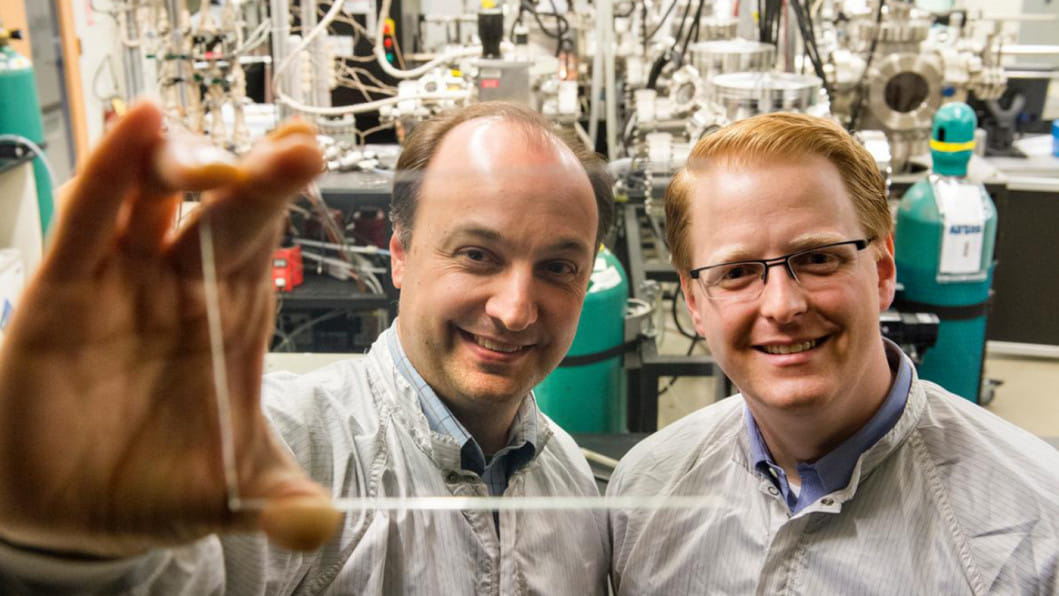

The solar material is deposited using a standard film coating process, all at ambient temperatures. Ubiquitous engineers are building organic photovoltaic structures 1,000 times thinner than a human hair.

Shayle Kann, senior vice president of GTM Research market research firm, noted the process cost advantage in a Reddit "Ask Me Anything" earlier this month.

But he said may be hard for transparent solar companies to gain access to enough capital to ramp up manufacturing, when their product will be pitted against well-established, more efficient conventional panels.

Barr says Ubiquitous plans to prove its technology first on a small scale. The company's pilot production facility in Redwood City, California, is currently working with mobile device manufacturers to design prototype smartphones, watches, and other small electronics powered by Ubiquitous technology.

"We think providing battery-life extension and solving battery life problems will be a very good entry point for us," he said.

It's not yet certain when transparent solar-powered mobile devices will be available or what prices will be. But Barr says the Ubiquitous team doesn't expect the technology to change the cost of the mobile devices significantly.

And don't look for a solar panel on your new sun-powered smartphone. If everything works out as the company hopes, the solar material will be an invisible coating under the glass over the device display.

"Ideally," Barr said, "it doesn't look like anything."

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments