Survey puts figure on fading cosmos

A team of astronomers has published a multi-coloured survey of five chunks of space - and offered the best estimate yet of how fast the Universe is fading.

They analysed the light from 200,000 galaxies in 21 wavelengths and found that the energy output of the Universe has nearly halved in two billion years.

This agrees with previous calculations, confirming that the lights are slowly going out right across this spectrum.

The drop is largely due to the falling rate at which new stars are formed.

The results, which come from the Galaxy and Mass Assembly (GAMA) survey, were unveiled at the general assembly of the International Astronomical Unionin Honolulu, Hawaii.

"We used as many space and ground-based telescopes as we could get our hands on to measure the energy output of over 200,000 galaxies across as broad a wavelength range as possible," said GAMA's principal investigator Prof Simon Driver, from the International Centre for Radio Astronomy Research in Western Australia.

He and his team are now opening up this huge collection of data for other astronomers to work on.

"The data release means that a whole lot more people outside the team are going to be able to jump on the data and do science with it, which is incredibly important," said Dr Stephen Wilkins of the University of Sussex, another GAMA team member.

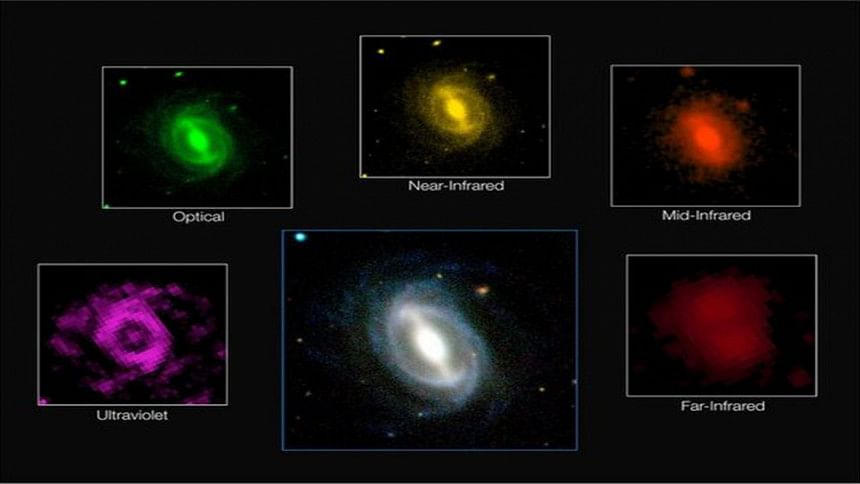

He told BBC News that the strength of GAMA is that it combines so many wavelengths, where previous surveys have concentrated on a few.

Because the team used a variety of the world's most powerful telescopes - both earthbound and in orbit - their analysis spans wavelengths from UV light to infrared, including the small strip of visible wavelengths in the middle.

That means they can look at light from stars that are both young and old, as well as light that has been absorbed and then re-emitted by dust. So the new assessment of the Universe's decline includes information from a huge variety of galaxies, including those hidden behind dust.

'Nodding off'

"We know that star formation peaked a few billion years ago and has been declining since. This is just a new way of measuring that decline," Dr Wilkins said.

"It's a new spin, and it completely agrees with the previous results - but it's tightened the error bars as well."

Specifically, when the team totted up the total energy output of galaxies at three different ages, they saw a steady slump. In total, from 2.25 billion years ago to 0.75 billion years ago, the Universe's output apparently fell by about 40%.

"The rate at which stars are forming is slowing down so much that we are now starting to see the total energy output of all the stars decreasing," Dr Wilkins explained. This happens because the stars that already exist - on average - get older, smaller and less energetic.

Prof Driver wrapped the findings into a sad but cosy analogy: "The Universe will decline from here on in, like an old age that lasts forever," he said. "The Universe has basically sat down on the sofa, pulled up a blanket and is about to nod off for an eternal doze."

The eventual end of the Universe is still an awfully long way off, the team said - and it is far too early to put a date on it.

"The rate at which stars form is probably going to decline more and more," Dr Wilkins said. "So the Universe will, based on our expectations, become fainter and fainter and fainter. But there's a huge amount of uncertainty there because we don't understand so much of the underlying cosmology."

The team's analysis of the great cosmic drowsiness has been submitted to the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, but is not yet peer-reviewed.

Dr Aprajita Verma, an astrophysicist at the University of Oxford, said GAMA offered a unique and valuable data set because of its spread of wavelengths.

"We know that galaxies can exhibit very different properties if you look at them purely in the visible, compared to other wavelengths," she told the BBC. "This study is making a census of their emissions, right the way from the UV through to the sub-millimetre range."

Dr Verma was also pleased the wider research community would get its hands on the data. "It will spawn lots of new studies," she said.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments