Good grades alone may not be good enough

For centuries, since the first university, Al Quaraouiyine in Fez, Morocco (est: 859 AD), universities have been a centre of learning. Young people would come under its wings. They'd leave when the university thought befitting. By the 1800s, this changed. Oxford and Cambridge were the first to introduce standardised final exams. It was a comprehensive exam that tested how much students retained. Schools and colleges in Britain soon adopted the Oxbridge model. Today standardised tests are universal.

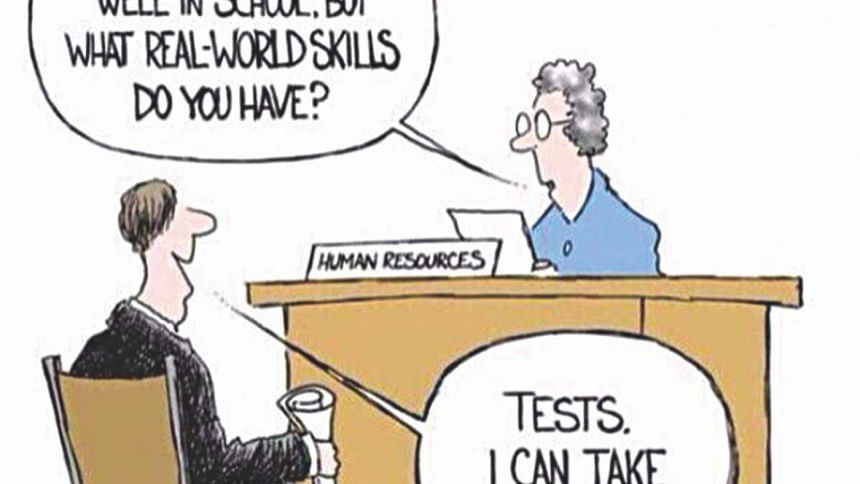

Standardised exams have an advantage. Others recognise our ability by looking at our result. We use our results as a signal as we move from playgroup, to primary, to high school, to college, and finally to university. The challenge lies when we leave the university and enter professional life. It's then we send the signal to an employer and not to the next education institute. Employers would like to know: are our grades a fair assessment of our ability to adapt in the workplace? The answer to this question has started a debate on re-thinking education assessment.

Ever since Oxbridge introduced standardised exams, assessment has been based mainly on written exams within a fixed time and an oral evaluation in some cases. The objective has been to see how much a student is able to retain. When time is fixed in an exam, thinking and answering means wasting precious time. Memorisation helps reduce the risk of failing or getting a bad grade. Doing well in exams also depends on how well a student is in not getting nervous. If you get nervous, your grades may not reflect your true ability.

A one-time exam, that's stood the test of time, unfortunately, fails to give some critical information. It doesn't tell how good a student is in persevering – if the student is good at working in a group; if they are willing to take an initiative, to learn from trial and error; and finally, if the student has empathy towards others. These questions are being raised nowadays because these qualities are vital for success in the workplace.

Conventional wisdom is to hire students with good CGPAs. However, the best students aren't necessarily the more innovative ones or able to take risks. Employers like Google who search for innovative candidates don't seek university grades as an important indicator to determine who they'll employ. Fifteen percent of their recruits have little or no higher education.

Universities in Europe and North America have started to change their attitudes. Nowadays, when I write reference letters for my students, I'm asked by universities to comment on extra-curricular activities, leadership qualities, and mental toughness. If you're asking why, the answer is simple. Universities today are both a centre of learning and a centre from where employers search for their employees.

As the world debates on how to make the education system adapt to changing times, you can adapt yourself because changes may not come during your tenure. What are you good at, outside studies? Only you know the answer to this question. Focus on the things you're good at in your leisure time. The more you utilise your leisure time, the more you develop a skill and also the love for a skill. Whatever that skill may be. By the time you're ready to enter professional life, you'll be able to show prospective employers a signal, or would have been able to learn skills to start an enterprise of your own.

Bill Gates and Mark Zuckerberg are university drop-outs, but they did fruitfully use their leisure time outside study to develop skills. This led to the creation of Microsoft and Facebook. Life starts after you finish formal education. How well you prepare yourself for it, is determined to a large extent by how you utilised your leisure hours in school and university. In today's competitive world, good grades alone may not be good enough.

Based on: The Why Factor. BBC World Service. Jun 12, 2017.

Asrar Chowdhury teaches economic theory and game theory in the classroom. Outside he listens to music and BBC Radio; follows Test Cricket; and plays the flute. He can be reached at: [email protected]

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments