Behind enemy lines: Story of a Bengali family stuck in Pakistan during 1971

The struggle for the liberation of our motherland is unique in many ways. To achieve the dream of a free and sovereign Bangladesh, people from all walks of life, religion and castes displayed unparalleled unity, bravery and spirit. Those nine months have created millions of stories of the ultimate sacrifice – small stories in contrast to the magnitude, which are engraved in the very fabric of our country's existence. It extends beyond the seven Bir Shrestho and even beyond the three million Bengalis martyred in those barbaric days.

As a person from a family with military background, I was always intrigued by that part of our liberation struggle. The military heroics and stories of some legendary battles are well documented. With time though, I realised that one crucial part of the military war hasn't been told of much – the plight of the Bengali militarymen and their families stuck in Pakistan at the time of the war.

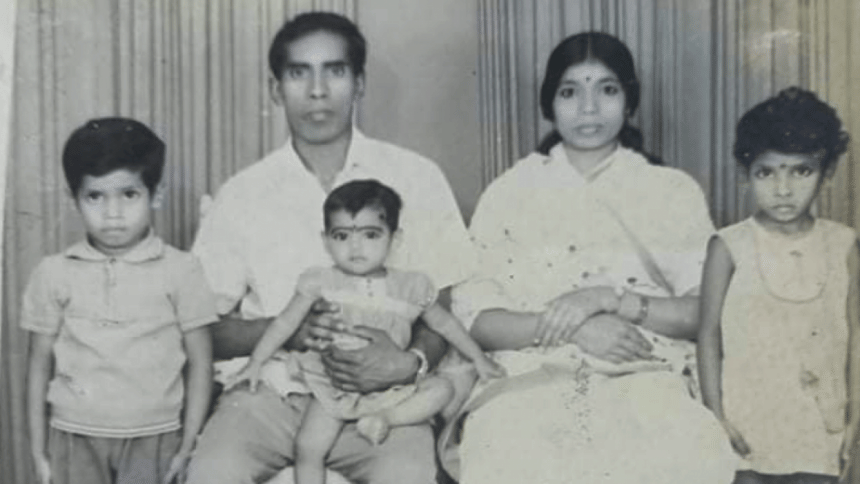

Dewan Arfan Mia, my late nana bhai, is an example of this. Talking to my grandmother, my nanu Nurjahan Begum, I realised just how tough it was for both my nana bhai and the family, stuck in hostile territory, but furiously patriotic and doing their very best to help our sacred cause and… just to survive to see another sunrise.

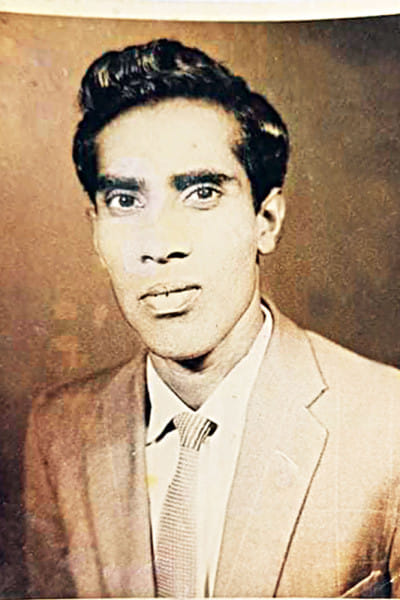

Nana bhai joined the Pakistan navy as a sailor at a very young age. As was consistent with that time, he faced discrimination every turn at his workplace. This only increased my nana bhai's already intense patriotic zeal. His love for the motherland never diminished and he did his very best to support the cause during the 1970 General Elections despite being a member of the military.

In that fateful March of 1971, as the green shoots of an impending war grew with each passing day, my nana bhai, then posted in Karachi, knew he had to be ready to support our liberation struggle in any possible way. The navy high command was alert about the Bengali sailors so they had banned them from travelling back to Bangladesh. If orders were disobeyed, there was a decree to take the whole family captive or even kill them all.

As the "Operation Searchlight" on the night of March 25 commenced the Liberation War, the Bengalis posted in Pakistan were immediately put under tight security. My nanu with my uncle and aunt, toddlers at that time, were put in a sort of a camp and separated from my nana bhai.

He was allowed to see the family only once in a while. Talking to my nanu, I got some fascinating insight on how my nana bhai helped our liberation struggle. His patriotic fervour had cranked up on the back of the events back home, but he had a family to protect as well. What he did was exceptionally tricky, and at times, emotionally stressful.

Security around the personnel was beefed up as soon as the war began. Spies were deployed all around the offices and the camp to fish out the Bengali sympathisers. Even their slightest movements were strictly monitored. They were treated quite harshly too – a slight change in their arrival time or activities, and they were immediately put under interrogation.

But that didn't deter my nana bhai or the countless other Bengalis who wanted to see their country free. He did his best to support the struggle from hostile territory, providing vital information to the fighters via secure channels, warning them of forthcoming attacks and at times giving them food off their own rations if possible via the Red Crescent.

They also campaigned, with the help of their interned families, to gain international support for the war, and some even tried to smuggle weapons and photos of the internment camps to help freedom fighters and gain the world's support. The stakes were high, and he had seen a few of his comrades captured right in front of him, never seeing them afterwards.

Being separated from her husband and having virtually no communication with him, my nanu had a tough time too. The living conditions weren't the best for a family with children to live in. Their supply of food and essentials were strictly rationed too. In her words, they got "a quarter of what they were entitled to."

As a mother, it was very tough for her. To feed her young children, she depended on the relief materials provided by the Red Crescent or the donations of sympathetic Pakistani officers. At one instance, she had to sell jewellery just to feed my uncle and aunt.

Against this backdrop, my nana bhai was "sent on a ship back to Bangladesh" near the end of the war. He was missing for a while and my nanu all but assumed he was dead. Fortunately, he was found alive after six months and he later joined the Bangladesh Navy. But whatever happened in the intervening time, if he was tortured or fought for our cause, was never known.

"He was probably traumatised so he didn't want to reminisce about that time, but we are very proud to have contributed to our liberation struggle, even though at a small scale," my nanu added.

There are countless stories like this without which our independence may not have been possible. On the 50th Victory Day of independent Bangladesh, it is our duty to protect these legacies to instil the patriotic fervour of our ancestors on to future generations to come.

Inqiad Bin Ali has "a pain in his heart and a love in his soul" to put it in an artistic way. He is found deep in thoughts at [email protected]

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments