Ramadan and young professionals

The perception of regular events taking place around you changes as you grow up. It's a well-known reality that is nonetheless jarring, and for a young person shifting gears from a life of classes and exams to one of meetings and appointments, these changes can be a challenging thing to come to terms with.

In the life of a young Muslim Bangladeshi, Ramadan is more often than not a highlight of the year. As a child, you grow up dreaming of the time when you will be able to fast every day. The teenage years are spent learning the spiritual significance of the act, and also obsessing over one's favourite items on the iftar menu. As a young person in high school or university, juggling classes and exams with the Ramadan schedule can be difficult, especially when a spanner is thrown into the works of a carefully balanced (or rather, imbalanced) sleep schedule with the addition of an extra post-midnight meal. Yet, it's all part of the fun because all of this is done surrounded by family, where the burden of responsibility to keep things running doesn't often fall on the youngest person in the household. A young person's Ramadan can be a vibrant social affair too, as the opportunity exists to attend gatherings with friends and family, with schools extending long holidays for Ramadan and Eid.

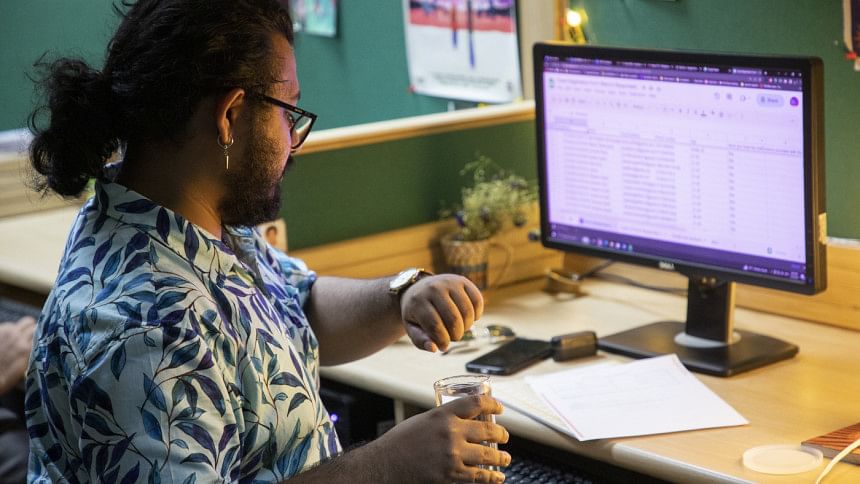

But as the exuberance of youthfulness makes way for the dreary realities of early adulthood, Ramadan changes in more ways than one. The festivities that took priority once upon a time have to be pushed back to the status of meagre entries on a routine. And the routine itself becomes a difficult game of whack-a-mole, where having to wake up for sehri might mean an incomplete night of sleep because getting to work early in the morning is necessary if one intends to get home on time for iftar.

"My sleep schedule has changed because I have to wake up early for sehri. I found it somewhat difficult because previously, as a student, I often had enough time to sleep after sehri but now I do not have that luxury as I need to go to the office," said Faiaz Amin Khan, a recent graduate who is now a Junior Software Engineer at Samsung Research and Development Institute, Bangladesh.

Wasima Tanzim, 24, is a Management Trainee Officer, Content Development at Forethought PR, and she echoes this sentiment.

"Waking up early hasn't really been the easiest. It is always a struggle, especially as work starts even earlier now. Although my workplace is a bit lenient in terms of timing, most workplaces aren't. For them, it's even harder," she said.

"My sleep cycle was somewhat normal before Ramadan. I used to sleep around 12 and wake up at seven. But now, since I still need to wake up at seven and have sehri before that, I am trying to shift my sleep cycle from nine to three but till now I have failed miserably. I went to sleep at 12 still, woke up for sehri and then at seven again and had to get 2 hours of sleep at work (luckily my office has a relaxation room for sleeping)," said Farhan Fuad, 24, a software engineer at a local tech firm.

Moving further along the day, the next struggle is the fight against Dhaka traffic to get to work on time, and then to make it back for iftar. Dhaka's notorious traffic tends to get worse around Ramadan, especially for younger professionals on a budget who don't have access to private transportation.

"Fighting for a place to keep my foot on public buses at the rush hour, especially after fasting for the whole day is not easy. Sometimes, I don't make it in time for iftar and my parents are rightfully upset on those days," added Farhan.

All of this leads to a level of physical exertion during Ramadan that young people would have been protected from during their student lives.

"I think it has gotten more difficult for me now because I have to work for 7 hours straight without any breaks. As a student, there would be breaks between classes and the overall hours I spent at school or university were lower," said Faiaz.

Farhan agrees that Ramadan felt easier as a student, "In university, I wouldn't have to be present strictly from 10 to 6. It was on average 5 hours per day and my university provided its own transportation, which made things much easier."

This tiring reality leads to the situation where young people finally have to grow up when Ramadan is no longer about frequent iftar parties with family and friends or long shopping sessions on weekdays. The choice has to be made to keep up with the grind of work, and at the end of the day, the social and community aspect of Ramadan is what takes a hit.

"I definitely can't meet friends and family during Ramadan as I used to in the past. Post-iftar hours are already tiring and an eight-hour office shift on top of it means I have hardly got any motivation and energy left to go out and socialise with others. I prefer staying home and trying to go to sleep early the next day," said Farhan.

Shoaib Ahmed Sayam, 25, works as a journalist at The Daily Star. His work hours mean he can only have iftar with his family at home once in a while. "When I was younger, Ramadan was all about family. When I became a teenager, I had a lot of iftar and post-Taraweeh hangouts with my friends. But growing up, getting a job, and the added responsibility has meant all I do during Ramadan now is wake up, get to work, have iftar there, and by the time I get home, most people's days are over. It makes me a bit sad but I have also made peace with it as not much can be done."

Perhaps, Wasima sums it up the best, "Ramadan or not, socialising has become significantly difficult anyway. It seems as though we have grown up."

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments