Season of the Black Leopard

In this village bordered by a sprawling tea plantation, many say that they have seen the leopard. Mostly during the night, when the moon hangs so low you can pluck it right off the darkness and eat it like some fruit.

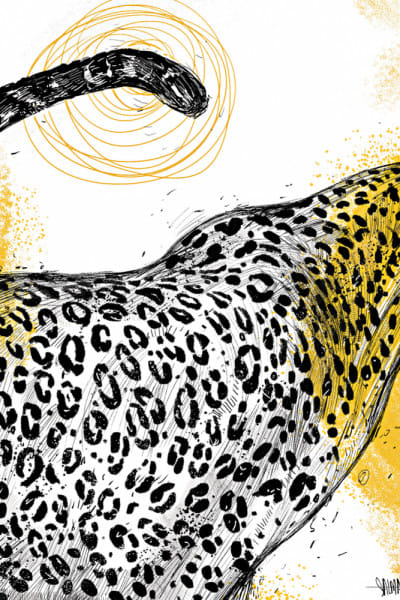

Black. Glossy in the moonlight. Its white whiskers asserting an implicit, involuntary dominance. Its supple body effortlessly sliding up and down the teak trees that are abundant here. A shadow – a dark emissary of the night – drifting among the plant kingdom like a fugitive.

Those who have not seen the leopard, wish to believe that it is a false imagination – one that has consolidated itself in the leopard watchers' consciousness like an unbreakable stone. They wish to believe that it must have been a civet. Or a marbled fishing cat. Or simply a black cat.

But the clawed scratches that clothe the teak trees' trunks, and the pugmarks that dot the sandy riverbank, the earth of the banana, jack-fruit, bitter melon plantations imply otherwise.

It is a matter of surprise that the leopard hasn't harmed anyone until now. The British rule came with its loud boots and left. Then a Partition made the earth wet with blood. Then a war. A new flag stirred the air. Not a single leopard attack.

Whenever Mohsin gets the chance, he tells everyone in the village how he stumbled across the leopard on several occasions during the war ten years ago. He was 20, and a fighter. If he didn't have a rifle slung over his shoulder or if he were completely alone during the encounter, he would probably faint or wet his pants, he says jokingly. The leopard's lithe movement came with no warning – no leaf rustled, no hoolock gibbon screeched, no wind blew over him and told him to run. So in that regard, he and the fighters of his crew had to remain careful when hiding from the marauding alien-tongued, olive-headed enemy in the vegetation, the thickets, around the fig, the peepal, the banyan, the teaks.

It was a cold, rain-bloated July night. Mohsin was installing a landmine, a few meters away from the enemy's camp in the forest. After finishing the task, as he took to his heels, he fell in a cave and was knocked unconscious. He woke up after an hour or so, his vision battered by the mad rainfall. Crawling his way out of the cave, he spotted the green eyes. His first encounter. Disbelief seeped into every nerve of his being. Was he hallucinating? Or was it actually a black leopard, an animal he had never seen? He kept staring at its hypnotic, electric green gaze. Until a gunshot from the camp or perhaps the main road rang in the air and reverberated through the forest, and they parted their ways.

Hamid, who was eighteen when he worked for the alien-tongued man who lived in a bungalow in the tea estate at the village's periphery during the war, is also one of the fortunate ones who have seen the leopard. Before the war, during the war, and after the war, when a new country was born with its new flag, when its people could speak their own language, dance at their own festivals. He remembers how the moon was a yellow boat in an aerial, inky, cloud-tinged river when he aided the fighters in getting inside the estate and blowing up the bungalow. He remembers how the black leopard's face was awash in gold when the bungalow was held captive by the long fingers of flame.

Just a few days ago, Asma spotted the leopard lingering around her chicken coop at night until she shooed it away with a siren scream. Krishna, the milkman, also spotted it prancing around the paddy field, in the fiery glow of his hurricane-lamp. Hasnat, the imam, saw it gracefully climbing up the banyan tree across the mosque, as he readied himself for the Fajr azaan. Khokon and his friends, after they finished killing a monitor lizard for some reason, saw it walking over the snaking rail tracks, holding a brown deer in its maw while the sun slowly disappeared, dusk crept in, and bats, crows, and kites headed home in loud mobs.

***

It takes the leopard five minutes to die. Five minutes. Its soul smokes out of its body. Snaking its way towards the heat-wounded sky against the seething sun. The leopard that felt the tremor of invaders in its bones when the country was under siege. The leopard that felt the boom of victory beneath its paws when liberation came. The leopard, the silent observer, the audience from the forest, the shadow with green eyes, white whiskers, a sleek body, a long tail.

They catch the leopard as it rests on one of the spaghetti branches of the banyan across the mosque. It is charged with the disappearance of three chickens from Osman the chicken vendor's compound. It is possible that monitor lizards did it. Or the marbled cats. Or the civets. But they charge the leopard because they, without any effort, find it resting on the banyan's branch, under which a few feathers remain unattended. It is a rare occasion – the leopard's effortless sight when the sun is out of the sea and up in the sky.

Only the squirrels, the rats, and the gibbons and other primates who were present at the crime scene know that it was a small legion of civets that took the chickens. That the charge placed on the leopard was pure fiction.

***

The next day, the leopard-free village wakes from a slumber and perceives the crazy irony of leopard-free-ness. There are paws poking out of the coppery earth, the jack-fruits, the pumpkins. The paddy fields are overrun by long whiskers that almost look like kashphool. So are the snaking rail tracks. Writhing black, long tails wound the banana plantations and the bitter melon plantations. They also dangle from the winding branches of the figs, the banyans, the peepals, and the bodhi tree at the center of the big field.

The village groans. The leopard laughs from up above.

Shah Tazrian Ashrafi is a freshman studying International Relations.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments