The grief of losing a skill

When I find myself sliding into the endless pit called writer's block, I turn to prolific writers. One of them is Emily Dickinson, who left an oeuvre of 2500 poem manuscripts — most of it written without any incentive of getting published.

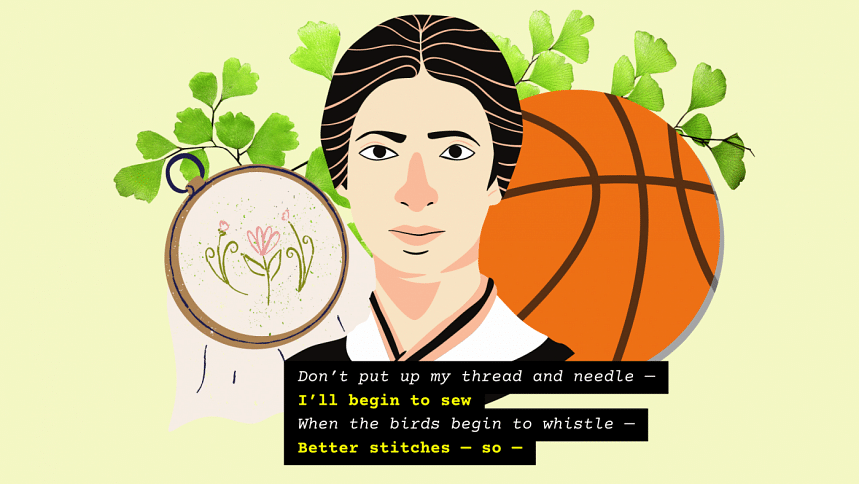

Perhaps to compensate for the perceived impossibility of publishing, women during those times used to hand-sew their poems into thin bundles called fascicles. Emily did so, too. But at one stage, she writes,

Don't put up my thread and needle —

I'll begin to sew

When the birds begin to whistle —

Better stitches — so —

Dickinson grapples with the fear of losing her stitches, possibly due to her eye disease that restricted working up close. She feared a distance with her thread and needle.

Undoubtedly, her most passionate art was poetry and sewing, perhaps a secondary hobby that aided the preservation of her poems. Yet, an autobiographical reading of this poem reveals her fear of losing this skill and the ensuing torment that led her to hem words into verses of sorrow.

My aunt too had put down her thread and needle. Anyone visiting her house can't help admiring the paintings lining her living room walls. They are beautiful from a distance but only upon closer inspection with squinted eyes does one make this surprising discovery — the vivid sceneries are not creations of brushstrokes. My aunt had the talent of capturing intricate vistas of flowers, butterflies, diverse foliage, honey bees, vines, and much more with minute stitches of thread and needle on canvas.

Whenever I visit her, I take one of those artworks and brush the tips of my fingers through the textured stitches of decade-old thread. My aunt brims with pride as I do. But I also trace the shadow of a wistful smile reminiscent of the youthful leisurely days. When my first cousin was born, she was busy embracing motherhood and couldn't even tell when her craft left without saying so much as a goodbye.

As my hands slowly sweep the stitches, I feel tactilely connected to my own sense of loss. I remember the textured rubber surface of a basketball against my palms. It brings back the afternoons we spent throwing the ball from different points, polishing our lay-up shots and fine tuning the force of our chest passes. When the heat of the game had worn us out, we sat with legs stretched and gulped lemonade with basil seeds. The view in front of us featuring the setting sun — an orange ball sliding down the hoop.

Nowadays, I see my passing out of cadet college as the symbolic sunset of my journey with basketball. With the benefit of hindsight, I can find a dozen excuses to explain away my insincerity towards holding on to the game. But none of it fills the nostalgic hollowness I feel when I come across an Instagram story of the lofty hoop hanging against the sunset sky.

Some departures are so slow and silent that we don't even notice that it's taking place. The busy days prolong. We put down our thread and needle. And one summer afternoon, we realise the pastimes we once took pride in have become glass-enclosed relics in the museums we carry in our heads.

Noushin Nuri is an early bird fighting the world to maintain her sleep schedule. Reach her at @noushinnurii on Instagram.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments