The sad state of Bangla literature in the national curriculum

Literature exists all around us, in tones and colours that are as varied as whatever meets the eyes and reaches the mind. It exists in little bubbles that are meant to be enjoyed by everyone regardless of their backgrounds. Stories, poems, novels, and plays have passed down traces of culture, identity, and society as a method to preserve the essence of one's being since time immemorial.

Bangla literature serves that same purpose for us, ornamenting our rich heritage and helping us find our roots. Whether it be Sukumar Ray's unique brand of humour or Michael Madhusudan Dutt's aching prose, the depth of Bangla literature can allure anyone willing to delve into a world of vibrancy and glamour.

However, for an overwhelming majority of national curriculum students, literary exploration of this sort is not even a pipe dream, rather something that can be regarded as mere fantasy.

The reason behind such a situation lies in the very foundation of our national curriculum. The confusions and complications that go hand in hand with it have made studying Bangla literature, out of all the subjects, a woefully difficult task for all parties involved.

Throughout a student's academic career, Bangla literature entails expectations of memorisation and internalisation of a myriad of purely fictitious facts with the sole intention of earning marks in exams. As a result, students grow a sense of resentment towards the entire topic, and fail to grasp the true essence of the literature they are presented with.

Our national curriculum's exam structure is largely at fault for misdirecting the students' perception of the subject. From sixth grade onwards, creative questions — which have been subject to immense criticism from students, guardians, and professionals alike — plague students and dictate their learning process in a skewed manner.

Shirin Akhter*, a lecturer of Bangla at St. Joseph Higher Secondary School and College, expressed her dissatisfaction at how creative questions derail students when it comes to studying literature.

"The biggest downfall of the creative question system is that it discourages students from thinking critically and analysing literary works from their own perspectives. One must understand that argumentative writing isn't always supposed to carry a yes/no solution, but creative questions demand that anyways," she laments.

Her opinions were echoed by Md. Jayed Sany, a second-year student of Bangla at Dhaka University. According to him, the system of creative questions is, undoubtedly, a major hindrance to studies, but in the case of Bangla literature, the trend of multiple-choice questions (MCQs) deteriorates the situation even further.

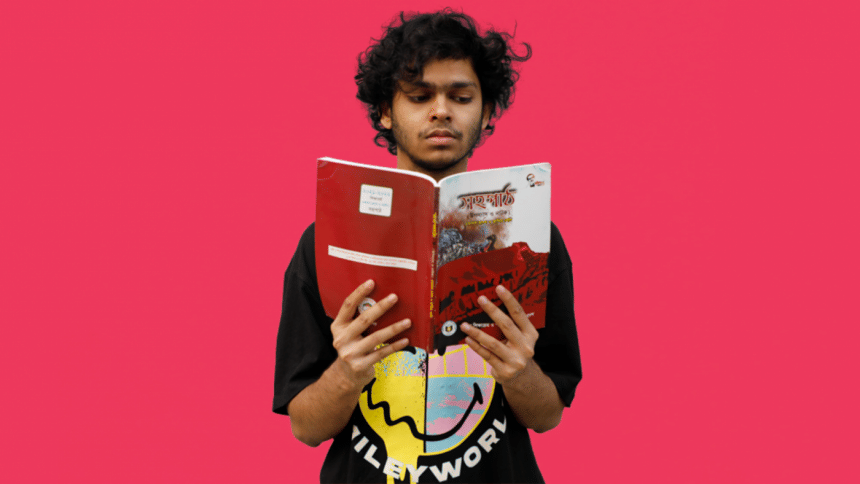

"By memorising the details in a story — not for personal satisfaction, but out of obligation – students miss out on the novel journey that the authors may have intended for them to experience," he said. "But since they must attempt MCQs in their exams, our pupils are more concerned with committing the characters' family trees to heart than they are with gauging the authors' underlying messages and motifs."

Moreover, the way textbooks are structured doesn't aid the process of learning either.

As it currently stands, students have to study a wide catalogue of fiction, non-fiction, poetry, drama, and excerpts from novels, all of which belong to different genres and feature different authors from various time periods. A lack of correlation between the included sections translates to a lack of comprehension which runs rampant throughout the books, thus making it difficult for students to commit to a particular style of literature.

As an alternative, Shirin suggests, "If the textbooks of each grade featured multiple works from distinct authors and followed a similar style, students could learn to appreciate and dive into literature more easily."

On the other side of the spectrum, it is worth noting that the English Medium curriculum approaches literature in a fundamentally different manner. English literature, in particular, has a far more comprehensive structure that reiterates the importance of understanding a piece of literary text with logical reasoning.

Tajrian Khan, a high school senior at Mangrove International School, who previously studied under the national curriculum, drew a comparison between the way literature was perceived in both spheres, "Literature studies in the UK curriculum is wholly different from NCTB in the sense that the former demands you to look at works of fiction through a critical lens, thus testing you on your literary and thematic analysis."

He further added, "You can choose to memorise a novel verbatim, but you might still fail the paper if you aren't able to form opinions and defend them well enough, since that's the goal of the subject. For the same reason, all exams are also open-book, saving you the trouble of memorising quotes so you can focus on what's actually important, unlike the national curriculum."

At the end of the day, indulging in literary works is a choice that is unique to the ones consuming it. While we cannot dictate the content one should or should not read, it must be ensured that there are no barriers to accessing and enjoying literature, as is the case with our national curriculum.

*Name has been changed for privacy

Ayaan immerses himself in dinosaur comics and poorly-written manga. Recommend your least favourite reads at [email protected]

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments