Where do I start with you, Milu?

After Milu died in 1954, his life's work was recovered from some black trunks in a corner of a grimy room at 183 Lansdowne Road. His sister Sucharita Das and poet Bhumendra Guha took responsibility for the preservation of these trunks. And to think that they almost lost these trunks, containing some 2500 poems, numerous unpublished short stories, essays, novels and his 4000-page diary, in the trams of Kolkata!

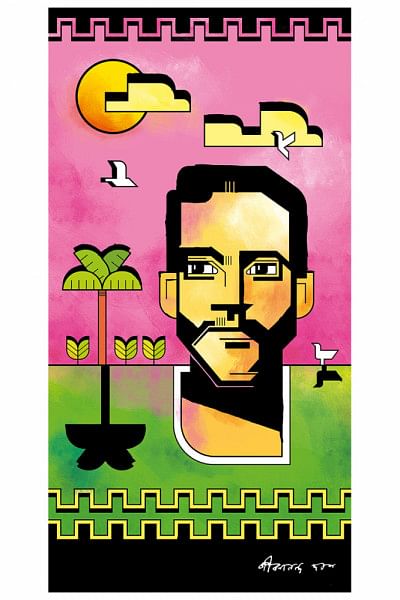

Born to a culturally inclined family, Jibanananda Das always had a questioning spirit in him. Unlike his mother poet Kusumkumari Das, he embodied an innate tendency of criticising cherished beliefs and institutions. Jibanananda despised the culture of Bengalis being satisfied with what he saw as mediocre, be it literature, music or their very way of life. This resentment at being mediocre is ironic for a poet who had a rather prosaic life.

Despite living in Kolkata, in the heart of the Bengali renaissance, introversion stood in the way of his deserved recognition. Tagore criticised him for heavy choice of words and metaphors whereas Nazrul's opinion of Jibanananda implied a hint of neglect. Despite being apprehensive and doubtful, Jibanananda stood by his poetry with conviction.

His poems had been described as surrealist, metaphorical, difficult, solitary and even obscene. Critics like Sajanikanta Das and Nirendranath Chakravarty were extremely vocal in criticising him for poems like "Bodh", "Campe", "Aat Bochor Ager Ekdin" and even "Banalata Sen", all of which laid the foundation for the phenomenon he later became. But Jibanananda believed his true readers weren't born yet, quoting the French author Andre Gide in his diary, "I do not write for the coming generation, but the following one."

But what made Kusumkumari's Milu the introverted loner that he was? Was it the heartbreak from his first love? Or perhaps his failed marriage? Dreadful years of unemployment, not getting deserved recognition, being tormented by critics and even his colleagues – all of this shaped the broken man that was Jibanananda.

Jibanananda's first and only love was his paternal cousin Shovona Das, to whom he dedicated his first anthology of poems "Jhora Palok", referring to her with the pseudonym "Kalyaniashu". Love, heartbreak and the gruelling pain that follows – he saw it all in his years at Assam with Shovona, which inspired hundreds of poems later on. After he got a job at City College and moved to Kolkata, their romance suffered a premature death. Jibanananda ended up marrying Labanyaprabha Das in 1930.

Immediately after the marriage, Jibanananda lost his job at City College. This was the beginning of five consecutive years of unemployment, a collapsing marriage and consequent clinical depression. The frustration of his failed marriage was gravely reflected in his novels during this period. In the novel Purnima, the vile male character wishes for the death of his wife and child, depicting Jibanananda's own frustration with his marriage.

Poetry, Jibanananda's only artistic language, tormented him throughout his life. "I- concerned from every point of view and suffering greatly materially, spiritually and what pains me infinitely- artistically…" he wrote in his diary. He was never a fluent speaker, which is why he struggled as a teacher. Although he finally got a job at BM College in Barisal, he realised he was never going to be happy with his career.

After 1947, he had to leave for Kolkata with his family where he got a job at the newspaper Swaraj. However, the chaotic workplace repulsed Jibanananda. Even after settling into a stable life which he craved dearly in his earlier years, his inherent restlessness and fatigue for life proved never ending. His diary, during this period, paints a morbid picture full of distressing thoughts. Even after 20 years of marriage, marital contempt was apparent in his novel Malyabaan, whereas his love for Shovona persisted in other works.

Jibanananda was never an ideal husband or the provider he was expected to be. In his funeral, where literary figures from all around Kolkata gathered, Labanyaprabha told Bhumendra Guha with a heavy heart, "Your dada left so much for Bengali literature. What did he leave me with?"

He didn't. Jibanananda Das was never meant to be here, in this vile cycle we call life. In his own last words, he could see "colours of grey manuscripts all over the sky" on his deathbed.

As a reader of your work who lives decades after your death, I can only wish I could hold your hands then, Milu, and tell you that this world was never meant for someone as beautiful as you.

References

1. "Ekjon Komolalebu" by Shahaduz Zaman

2. Roar.media (February 17, 2020). Ekjon nirjontomo kobi Jibanananda.

Suggest Ifti nonfiction at [email protected]

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments