Why students cheat

The use of unethical measures among students is widespread, even though it has always been looked down upon. In recent years, however, reports of massive question leaks in public exams, of brazen plagiarism and cheating in all levels of academia have not been hard to come by. It begs the question of whether the scope of this problem is simply confined to classrooms, or if it has roots that are actually systemic.

This week, we tried to explore these curiosities. A small scale survey was conducted online, the focus of which was to understand the underlying reasons behind the use of unethical measures in academic activities. For instance, 68.8 percent of students surveyed attributed "Desperation for better grades" as something that drives them to cheat. We spoke to some students to understand where this desperation comes from, and what it makes them do.

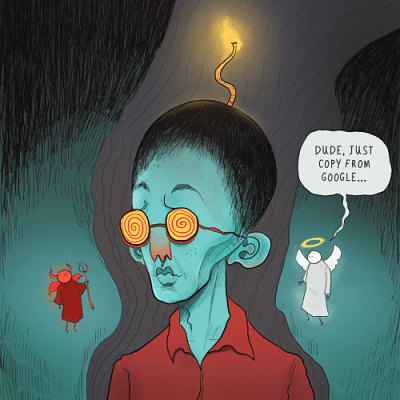

"I have experienced severe anxiety from being under the constant pressure of having to receive good grades. Whether it is the overall academic pressure or the one being exerted by my family, I had a tough time coping with it," said Fareeha Zaman*, a grade 12 student at a reputed English medium school in Dhaka.

She continued, "I was expected to constantly seek the highest grades, which led me to forget the importance of the content being taught and made me take the shortcuts required to achieve what was expected of me."

An interesting find according to the survey was that more students use unethical measures in exams (86.8 percent) than they do for an assignment (70.3 percent), which leads us to an important realisation.

Assignments, with ample time and opportunity to make as many revisions as possible, provide students with the opportunity to truly explore the subject matter and learn. Whereas exams, with their high stakes and the way they are conducted, often tend to take the learning out of the equation.

This makes us question the high stakes nature of exams, where way too much depends on the brain's performance during a short period of time, regardless of external factors. In the survey, 82 percent of respondents said they wouldn't use unethical measures if the education system was modified in a way that put less importance on grades. Which means students do not want to cheat, but feel compelled to do so.

We spoke to Foysal Aziz, lecturer at the Department of Mathematics in Notre Dame College, Dhaka, about the huge importance that is put on grades and whether it really needs to be that way. According to him, the problems are deep-seated, and the solutions need to match that, "If we look at our society, every family wants their children to succeed, the definition of which is often limited to just a couple of professions. In a broader sense, the target most students want to achieve through education is not enlightenment, but to establish themselves in society. This leads to too many students targeting the same goals, and in the end, teachers are left with no option other than relying on grades to evaluate this huge number of students with similar goals. This problem is systemic, and there needs to be an overhaul."

Galib Rahman*, a class 10 student at a renowned Bangla medium school in Mohammadpur, Dhaka, shared thoughts that add to this argument. "One reason I feel compelled to better my results in exams through cheating is that even if I stay honest, someone else who's less deserving might get ahead because they don't care about honesty," he said. From his perspective, using unethical means is the norm, and not adopting it puts him at a disadvantage compared to other students.

What further exacerbates this problem is unnecessary competitiveness in education, which was apparent in what Galib had to say. While many schools have moved away from the practice, ranking students according to their performance in exams does breed a toxic culture.

A recurring theme was noticed from the open answers section on our survey – students often find certain subjects, and the exams on those subjects to be irrelevant or unnecessary to their ultimate goals. This speaks the story of a disconnect, because we know university courses are carefully set, and whether or not a subject will be taught in school is the result of a curriculum set according to overarching education policies.

"There is clearly something lacking from the teachers here," said Foysal Aziz, when asked about this disconnect. "Similar to students, the reasons behind many teachers coming into the profession are not what you'd ideally want them to be. As a result, they fail to inspire students, to really sell them on why they need to study what they're being taught."

Arpan Ghosh* studies Software Engineering at Shahjalal University of Science and Technology, a major he's passionate about. He gave an account of his experience with cheating that supports this notion, "When I was in school, cheating was normal for me. Now that I'm studying something I like, however, when I know learning something will be helpful, and cheating would make me learn less, I am less inclined to cheat."

According to our survey, the second most popular answer when asked for reasons behind cheating was "Difficulty in rote memorisation". Exams in our country largely depend on a student's capability to remember facts and figures that basically leads to students depending on cram sessions and rote memorisation of content the night before the exam. These methods not only cause students to forget most of the content in the long run, but the students also never truly get to explore the subject matter on a deeper level.

Furthermore, this way of learning gives students with good memory and memorisation skills an unfair edge to perform better than students who have difficulty doing so. On the flipside, many students aren't blessed with a sharp memory, many suffer from test anxiety or other conditions that affect their attention span or learning capabilities, even though they may have the necessary skills of inference and reasoning needed to succeed in the Internet age. These students often resort to unfair means of getting by exams that inherently rely on skills they don't have, or need for that matter.

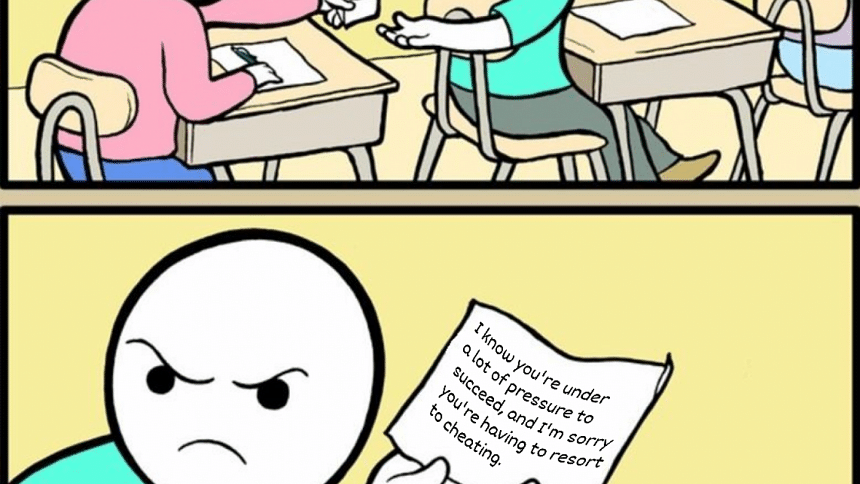

When it comes to teachers opinions about why their students cheat, most tend to believe that students who cheat do so out of habit or laziness, and they should be punished for their actions.

Noora Shamsi Bahar, a senior lecturer at the Department of English and Modern Languages of North South University said, "I've seen cheats cheat again despite being punished or penalised. It almost seems as if it's their second nature. Perhaps they do not realise that cheating is a serious offense and this is because they are never given any serious forms of punishment such as suspension or expulsion." However, almost all exam papers and instructions come with a warning that using unfair means has negative consequences. Most institutions even follow through and punish students by cancelling exams, failing them, or taking more serious actions. But students of these institutions still resort to cheating.

Fahima Iqbal*, a student of University College London says, "I used to cheat a lot in school, but stopped completely in university. It's largely because of the assistance provided by the institution to prepare the students, and the way we are treated after receiving the grades. In school, I was told that I would not succeed in my academic endeavour because I failed a test. Here, the professors and teaching assistants at the university helped us rectify our grades in case we failed."

So, the question we must ask is if punitive measures quell cheating in classrooms. If they don't, then there must be a way for the system to make changes that allows the situation to change. Most institutions offer punitive measures like humiliating, shaming and stigmatising students when it comes to disciplining students for being dishonest, whereas restorative practices allow students to reflect on their actions and learn better. This approach may allow students to take responsibility for their actions, and would reinforce the importance of academic honesty in their lives and the choices they make.

*Names changed for privacy

Azmin Azran is a sub-editor at SHOUT. Find him at [email protected]

Syeda Afrin Tarannum would choose 'The Script' over 'G-Eazy' any day. Continue ignoring her taste in music on: [email protected]

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments