A mansion has many rooms…and stories

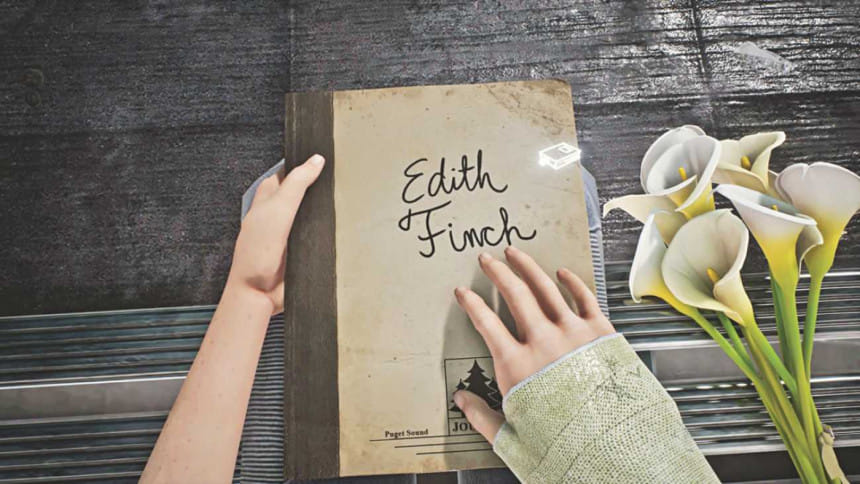

What Remains of Edith Finch is a game by Giant Sparrow about what death does to a family.

The titular character is a young woman returning to her ancestral home after many years. The house is tall and ramshackle, clearly having been added to repeatedly since its first construction. Edith is the only one there. Through the rest of the game you discover why.

The Finch clan arrived in America from Norway three generations ago. The family tradition is that each Finch has their own room, and no room is ever reused. A dead Finch has their room shut off and barred, an untouched sort of shrine to the person they were. And there are a lot of shut rooms. The Finches tend to die, and die young. A lot.

Using a series of clever passageways and little tunnels built-in the walls and crawlspaces of the old house, Edith bypasses the locked doors and enters into the rooms of her departed relatives. Each one is beautiful, carefully-designed by the art team to tell you everything you need to know about all these people. It's a sprawling clan but thanks to sheer love and care, every Finch stands out as a distinct member of the cast, even if you only see them briefly.

And you do see them. Each room holds something – a diary entry, a poem in memoriam, a letter from a psychiatrist – that sheds light into how the person died. As Edith reads, the first person perspective changes and suddenly you see through the relevant Finch's eyes. It's a simple conceit, but powerful as Giant Sparrow finds ways of using the first person experience in entirely novel ways, and even abandoning it when the context calls for it.

Everything available is used in the service of the story-telling: the first person perspective becomes the camera in a series of snapshots of a camping trip, simply holding down the mouse causes a picture book to flick through a fantastical story, and – in a sequence that steals the show – the dual-nature of mouse-and-keyboard controls comes into play when a character begins to daydream at work. The mechanics of the stories are occasionally a little frustrating but never enough to overcome the wonder of experiencing them. The "walking simulator" genre is often derided for limited interactivity, the character often just moving around and stumbling across plot. While low-interactivity is not necessarily a bad thing, What Remains of Edith Finch is by far the gold standard that shows what is possible to achieve when stories are genuinely designed to be experienced through active manipulation.

Each story – as with the characters and mechanics – is its own little microcosm of genre and tone. One story is brilliantly told via the panels of a shlocky horror comic designed to provide the reader with violent pleasure – except, of course, it tells the story of someone who really died. The contrast works, and even the most mechanically simple stories have this level of emotional complexity and contrast. Take the story of Gregory Finch. Moving a child's bath toys as if by magic, making them sing and dance would in any other story be delightful and frivolous; when you know how it ends and what it does to the other tragic characters you have met and known, it's heartbreaking.

It takes courage and skill to write tragedy like this. It takes a tremendous understanding of games to present stories this way. The result deserves to be experienced.

Zoheb Mashiur is a prematurely balding man with bad facial hair and so does his best to avoid people. Ruin his efforts by writing to [email protected]

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments