My Private Country

"I was so moved, Your Excellency, by the people's stories that I took the liberty of promising them that in future you will only kill them for crimes they commit."

– John H. Harris, Missionary in the Congo Free State.

In November of 1871, the Welsh journalist Henry Morton Stanley successfully found the long missing, legendary medical missionary David Livingstone. This feat gave Stanley the star power needed to have his own explorations funded by the newspapers. Starting from Zanzibar in 1874, Stanley spent 999 days mapping the entire length of the Congo River. Emerging from his expedition with half of it dead, he enthralled the colonial powers with stories of untapped riches and native peoples who could benefit both from modernisation and Western Christianity.

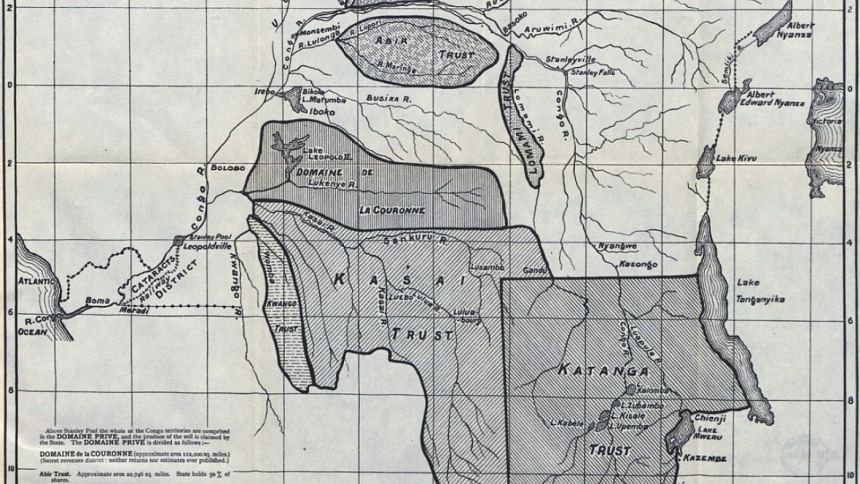

Perhaps Stanley's most attentive follower was the king of recently independent Belgium, Leopold II. Leopold viewed a colony as vital to elevating Belgium's status among European nations, and to circumvent his country's unwillingness to finance one, he hatched a scheme. Starting in 1876, Leopold began setting up, by proxy, a string of humanitarian organisations (including the Association internationale du Congo) that were fronts for a private holding company. Under this guise he hired Stanley in 1878 to revisit the Congo as his secret agent. Stanley's task was to beguile the native chiefs of the Congo to sign treaties with petty gifts and parlour tricks; though the chiefs did not understand it, they had signed away all rights to their land. On the summed strength of these treaties and his public face as philanthropist and enlightener, Leopold II approached the international powers at the Berlin Conference of 1884-85 with a proposal to allow him to run the Congo as head of the Association internationale du Congo. Leopold promised to promote the spread of Christian civilisation and humanitarianism, abolish slavery, and most importantly, to promote free trade between the powers. And thus, Europe and the USA consented to the formation of the Congo Free State, owned by Leopold as a private person.

It was 76 times the size of Belgium.

Behind the façade of well-meaning Europeans working hard to build hospitals, schools, churches and roads, there was theft, slavery, torture, murder and systematic mutilation. Successive decrees robbed the Congolese of the rights to their land and forced them to harvest and sell ivory and rubber to Leopold's administration (so much for free trade). Rubber was an increasingly valuable resource in a world that had begun electric wiring and just invented the inflatable tire, and Leopold saw it as the colony's way of paying for itself. Each village was assigned strict quotas of rubber, which if not met would result in death, administered by the Force Publique – Leopold's private army of slaves and cannibals. Congolese went to great lengths to meet these quotas, including slashing rubber vines wholesale instead of tapping into them to speed sap gathering. This destruction of rubber vines was also, unfortunately, punishable by death.

The bullets given to the Force Publique for their executions were given on suspicion that the 'soldiers' would use them for hunting game. To prove that every bullet fired was used on a human, Leopold's enforcers would have to produce their victims' severed hands for their white officers. The lack of proper coverage of security forces and scarcity of officers allowed the villagers to collude with their oppressors to pay off quota shortfalls with their hands. Entire villages would go to war for these hands, with many victims learning to play dead through the amputation and then escaping. The basket of hands became the symbol of Leopold's enlightenment of the 'Dark Continent'.

Arguably the rest of the Force Publique's activities are far worse; but suffice it to say that the antics of an armed, under-supervised and mistreated cannibals and slaves with an alien population at their mercy cannot be described in a youth publication. Luckily for human conscience, there were contemporaries who did describe it.

Leopold's reputation as philanthropist and evangelist held firm at first, even in the face of many foreign missionaries defying his threats and censors, and beginning to describe the atrocities they had witnessed. The most prominent early challenger was George W. Williams who in 1890 penned an open letter to Leopold, flaying him for his crimes. While Leopold's propaganda agents battled Williams, a journalist named Edmund D. Morel noticed that Belgian ships would come to port bearing rubber and ivory and leave with weapons and ammunition. Morel's investigations into Leopold's regimes brought him to the attention of Roger Casement, the British consul to the Congo who had been sent to investigate the situation. Casement's reports confirming the horror swayed public opinion, and he helped Morel start the Congo Reform Association in 1904. The CRA also had a great champion in Joseph Conrad, whose 1899 novella Heart of Darkness may now be seen as a study of the human mind but at the time was a telling account of life in the Congo Free State.

Come 1908, Leopold was buckling under the weight of his discovered crimes. He was forced to sell his private country to the Belgian government, inaugurating the Belgian Congo – which was not much better. Leopold died the following year, and his funeral procession was booed.

The Belgian Congo gave way to The Democratic Republic of the Congo. Decades of brutality and exploitation at the hands of absconding foreigners had not left the new state in an enviable position. Africa's stereotypical image as a jungle hell of brutish instability is the ghost of King Leopold II stalking the Congo Basin.

Ref:

Crichton, M. (1980). Congo.

Rivero, M. From Kongo to Congo: the History of the Belgian Congo (to 1963).

Hochschild, A. (1999). King Leopold's Ghost: A Story of Greed, Terror, and Heroism in Colonial Africa.

Williams, G. W. (1890). An open letter to His Serene Majesty Leopold II King of the Belgians and Sovereign of the Independent State of Congo.

Red Rubber: Atrocities in the Congo Free State in Confidential Print: Africa. (2010).

Morel, E. D., & Johnston, H. (1907). Red rubber: The story of the rubber slave trade flourishing on the Congo in the year of grace 1907.

------------------------------------------

Zoheb Mashiur is a prematurely balding man with bad facial hair and so does his best to avoid people. Ruin his efforts by writing to [email protected]

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments