The Hottest Trend in Medieval Japan

"Hereafter, the guns will be the most important arms. Therefore decrease the number of spears per unit, and have your most capable men carry guns."

– Takeda Shingen, 1567

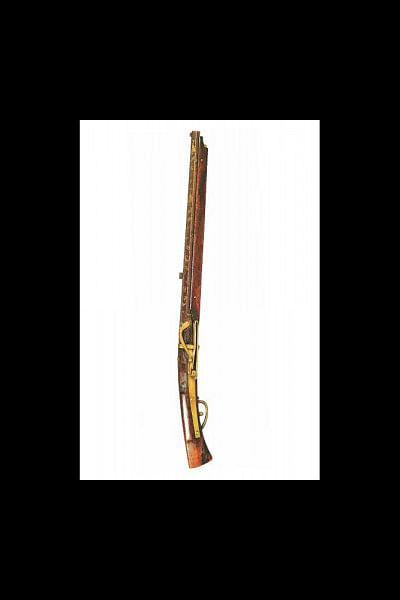

In the year 1543, a Chinese ship caught in a storm sought shelter on the island of Tanegashima, Japan. On board were Portuguese adventurers – a legitimate profession at the time, a bit like a homicidal tourist. The Portuguese were armed with arquebuses, primitive firearms you loaded from the front and fired using a match and locking system. The arquebus was leagues ahead of the firing tubes the Japanese had been familiar with up to that point, so the lord of Tanegashima was quick to buy two of them from the Portuguese. He set a swordsmith to copy the design and after a year and a little more Portuguese help, the first Japanese firearm was manufactured.

Within ten years 300,000 more rolled out of the forges, and they were being used and made all over the islands. In much the same way that honda is to many Bangladeshis the word for 'motorcycle', the gun-loving Japanese took to calling their weapons tanegashima.

To talk about warfare in Japan is to talk about the samurai class. Pop culture has these professionals turn up their noses at guns, which are weapons that even a child can pick up and kill anyone with – which just goes to show that even the 16th century Japanese understood guns better than modern Americans. Honour aside, early firearms were generally inferior to archery anyway: they were clumsy, needed more industrial support, were no good during in the wet, couldn't fire over obstacles, were short-ranged, and were quite weak.

So why would the samurai use guns at all? Because the tanegashima appeared in a period known as Sengoku Jidai, a century-long free-for-all where the various nobles of Japan bucked against the authority of the Shogunate and vied to install themselves in its place. A war of such proportions will be costly in terms of bodies, so which lord wouldn't want a weapon you can teach a peasant to use in under a day?

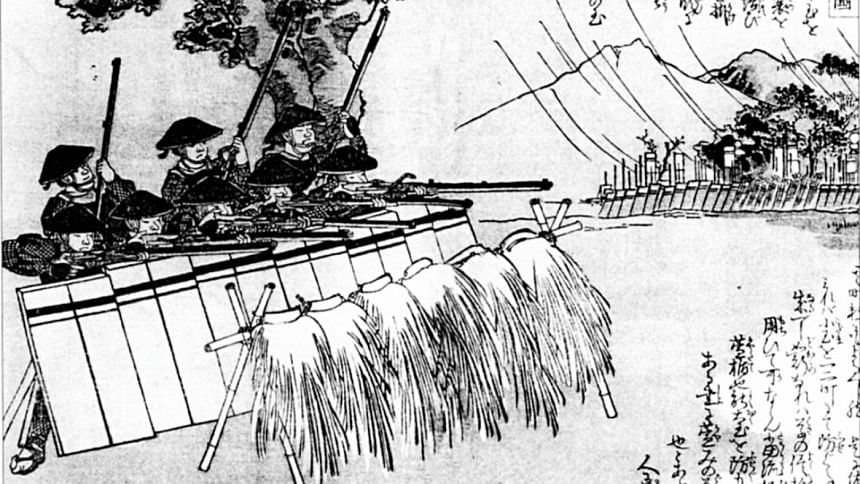

Japanese military minds dedicated themselves to fixing the deficiencies of the firearms, and did so faster than their European counterparts: range and calibre were improved, a serial firing technique was developed to allow soldiers to alternate firing and reloading with their fellows, night combat was made possible using string to measure fixed angles, and they even made an accessory to allow guns to be fired in the rain – something they never achieved in Europe. (Asians outperforming white people; don't see that every day.)

One problem the Europeans didn't have to contend with was gunners wasting time bowing and introducing themselves to their opponents first, but the Japanese eventually learned to dispense with the courtesies.

Takeda Shingen, quoted at the start of this write-up, was typical in his enthusiasm for tanegashima, an attitude that perhaps did his clan no favour after his successor was defeated by Oda Nobunaga who'd taken Shingen seriously and brought 3,000 guns to the fight. One of the shoguns installed during this period of National Musical Chairs even found time to invade Korea for a bit using an army including 160,000 gunners. The guns were too powerful for their own good, capturing Seoul within 18 days – the army moving too fast for its own supplies to catch up with it, eventually causing the invasion to collapse.

By the end of Sengoku Jidai the Japanese had produced so many guns that they may well have outpaced every European country. And then, nothing. In the gun's moment of triumph, the Japanese gave it up. Why is a story for the next time.

Zoheb Mashiur is a prematurely balding man with bad facial hair and so does his best to avoid people. Ruin his efforts by writing to [email protected]

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments