Musical versus Dance-drama

More than once I have written in this column that Bangla theatre lacks musicals though we have a reasonably long tradition of dance-drama introduced by Rabindranath Thakur. As Wiki defines it, 'Musical theatre is a form of theatrical performance that combines songs, spoken dialogues, acting and dance,' while dance-drama, as defined by Merriam Webster, is a 'Drama conveyed by dance movements sometimes accompanied by dialogue.' Rabindranath happens to be the pioneer in composing dance-drama for our stage—which is popularly known to us as Nritya Natya. Although he often included dance in many of his plays,in the real sense of the term he wrote only three dance-dramas of tremendous aesthetic value: Chitrangada, Chandalika, and Shayama. Rabindra Nritya Natya is much of a dance performance than spoken dialogues or narratives where expressive dancing dominates albeit many modern-day performing gurus take the liberty of infusing Odissi, Kathak and Kuchipud in his dance-dramas.

So what makes musical drama different from dance-drama or vice-versa? In musicals we find songs, spoken dialogues and, acting and dancing. In contrast, in Nritya Natya (dance-drama) the prime accompaniment in the performance is dance movements, and occasionally dialogues. So, in the first the plot or storyline is unfolded through four performing devices—songs, spoken dialogues, acting and dancing—but in the latter narration entirely depends on dance, and rarely on dialogues. This comparison of mine does in no way mean that I am trying to undermine one of them—it is in fact intended to find out the differences between those two genres, if there are any. Frankly, on several occasions I have sought to figure out the aesthetic differences between the two and to my utter confusion I have become aware that there exist disagreements regarding the matter among the persons au fait with performing arts in our country. However, my personal belief is, there are considerable differences between musical and dance-drama, and that particular belief of mine has impelled me to draw the conclusion that the concept of musical theatre is somehow remains disused in our performing genres.

We in Bangladesh have a very fertile folktale tradition, a folklore genre that typically consists of a story passed down from generation to generation orally, and it includes ballads, fairy tales, myths, legends, traditional song and dance, folk plays, jatra, seasonal events and child-lore. So it encompasses a wide range of narrative performances dominating songs and dances. Perhaps one particular performing genre closely links with musical is jatra, where we find songs, spoken dialogues, acting and dancing combine.

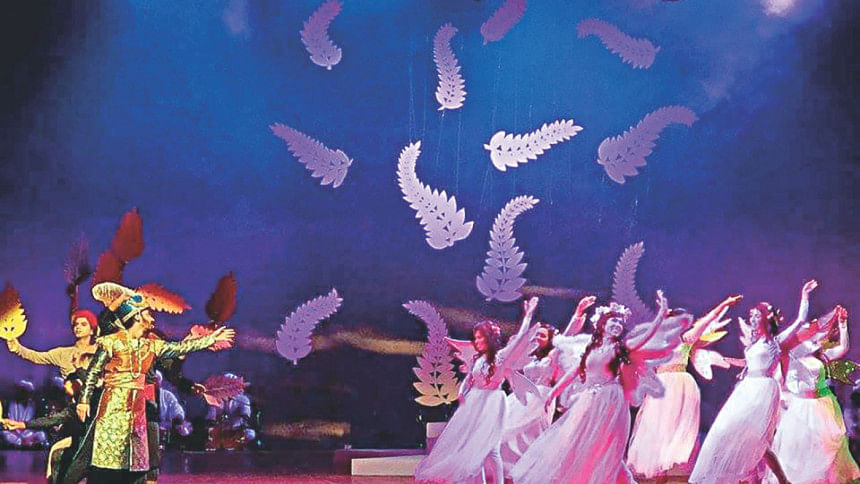

Recently Nagorik Nattyangon compiled a folktale, Gahor Badshah and Banesa Pori, for the stage and they have had several successful performances so far. The story is collected from our folk tradition and transformed into a musical by Hridi Huq — I say musical because it has almost all the requisites of a musical that I discussed above—songs, dialogues, acting and dancing. The storyline is more like jatra but it has a covertly non-linear narrative in the sense that there exists—as is the tradition with such folk stories—a lot of departures and treatments of magic realism. The most striking components the play contains are, songs, sets and props fittingly accompanied by lights. Using loud colours in all of them, in keeping with the disposition of the folk narrative, the director—once again it is Hridi Huq — has displayed her refined understanding of the aesthetics. The other approving count of the work happens to be synchronization of a huge cast. My experience of plays with huge casts is so far very disappointing—I have seen most of the times such plays wither away within no time mainly because of lack of harmonization, both on the stage and outside. Though I do not know how many shows Gahor Badshah and Banesa Pori has done so far, the group is going steady with their performance until now, and I am sure it has the inbuilt potential to carry on a long way.

Going back to my basic premise that we in Bangladesh have a big vacuity of musical theatre I wish to give a supporting welcome to the Nagorik Nattyangon for their genuine as well as efficacious effort in initiating the practice of musical theatre in this country.

The writer is an educationist teaching English Language & Literature at Central Women's University. He is also a Bangla Academy awardee for translation.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments