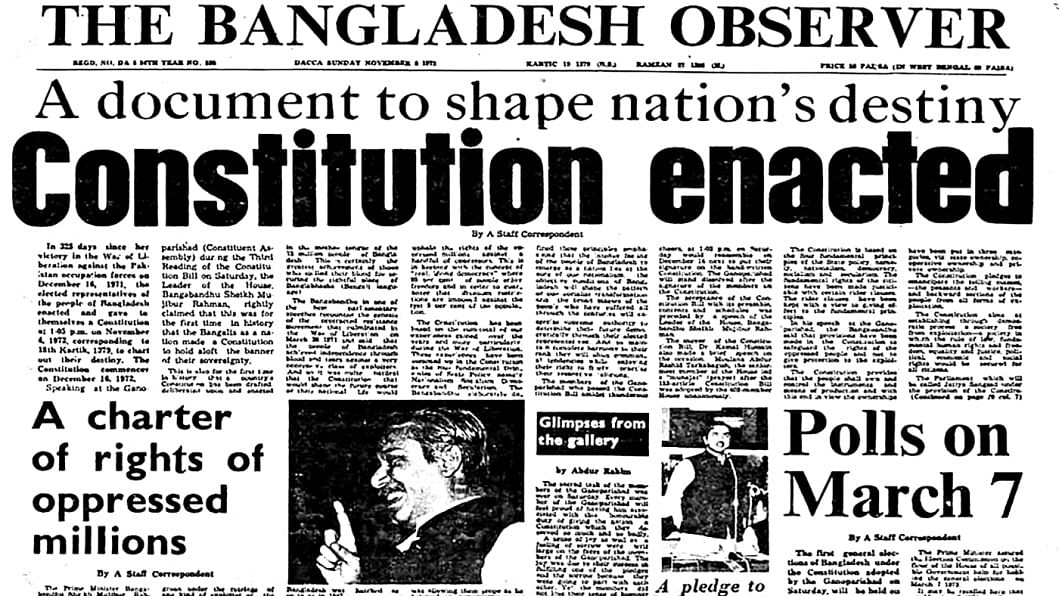

The Constitution of Bangladesh, adopted in 1972 following the nation's struggle for independence, stands as a testament to the collective aspirations of a people determined to shape their destiny through democratic self-rule and participatory governance. Drafted in the spirit of post-liberation optimism, the Constitution was envisioned as a living document, rooted in the principles of nationalism, socialism, democracy, and secularism—values that were seen as a response to counter the oppression and marginalization endured under Pakistani rule. Yet, Bangladesh's constitutional journey has been far from straightforward. As explored in my book The Constitution of Bangladesh: People, Politics, and Judicial Intervention, the evolution of this foundational text reveals a dynamic and often contentious interplay between the forces of public participation and the persistent threat of authoritarianism.

This article critically examines the Constitution's evolving history, placing its creation and transformation within the broader socio-political context of Bangladesh. While the initial drafting process emphasised public participation, subsequent decades witnessed a series of constitutional amendments that have both broadened and restricted democratic engagement. The constant shift between democratic ideals and authoritarian impulses has not only reshaped the constitutional landscape but has also revealed weaknesses in a system where legal structures can be manipulated for political gain.

Judicial intervention has played a crucial role in this evolving narrative. At times, the judiciary has emerged as a defense against authoritarian influence, upholding constitutional principles and safeguarding fundamental rights. Landmark rulings, such as Anwar Hossain Chowdhury v. Bangladesh (1989), which established the basic structure doctrine, exemplify moments where the judiciary sought to preserve the Constitution's core values against government overreach. However, there have also been times when the judiciary yielded to political pressure, validating executive overreach and contributing to the steady weakening of constitutional safeguards. This constant struggle between judicial independence and political influence highlights the delicate balance on which Bangladesh's constitutional democracy depends.

The Constitution's evolution is closely tied to broader struggles over national identity, political legitimacy, and the role of popular sovereignty. The tension between the people's aspirations for meaningful participation and the recurring push toward centralized authority has created a shifting and sometimes unstable constitutional order. As this article will show, the Constitution of Bangladesh remains a battleground—where the ideals of inclusive governance constantly clash with the realities of authoritarian control, each influencing the other in a complex struggle that shapes the nation's legal and political path.

HISTORICAL CONTEXT: FROM LIBERATION TO LEGAL FRAMING

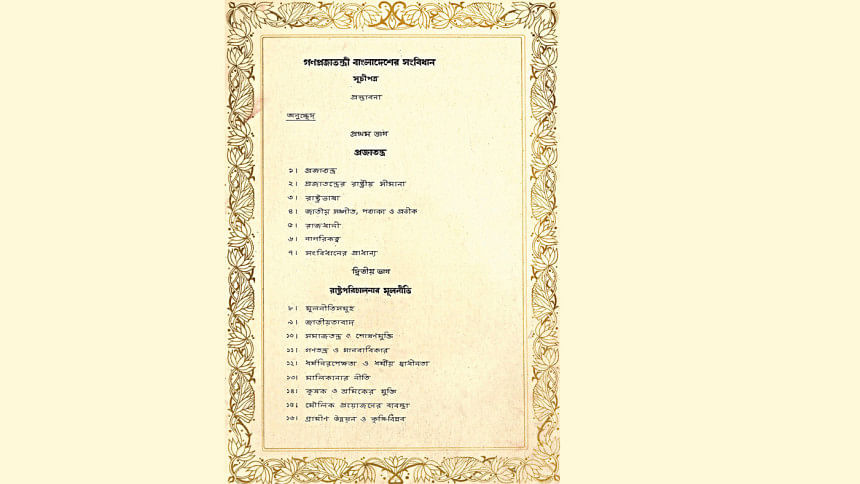

The Constitution of Bangladesh, adopted in 1972, stands as a powerful reflection of the nation's aspirations following a brutal liberation war. Rooted in the ideals of nationalism, socialism, democracy, and secularism, it sought to capture the determination of a people breaking free from years of oppression under colonial rule and Pakistani domination. The framers envisioned a document that not only embodied the hopes of an emancipated nation but also established safeguards to protect and promote those ideals. A parliamentary system was chosen as the governing framework, built on the guarantee of fundamental rights and an independent judiciary—key pillars meant to ensure public participation and prevent authoritarian overreach.

Yet, the ideals of the constitution quickly ran up against the harsh realities of political power struggles. The Fourth Amendment of 1975 became a clear example of this shift, replacing multi-party democracy with a one-party system and concentrating power within an executive presidency. This move not only restricted democratic participation but also silenced dissent, leading to an environment of political repression.

The subsequent Eighth Amendment in 1988 marked another shift from the constitution's foundational ethos. By declaring a state religion, the amendment weakened the secular character of the state—an act that significantly undermined the inclusive spirit of the Liberation War. This shift, driven more by political expediency than genuine public will, reflected the growing tendency of regimes to manipulate constitutional ideals for short-term political gain. These amendments illustrate the dynamic tension within Bangladesh's constitutional journey: a persistent struggle between the ideals of popular engagement and the encroachment of authoritarian impulses, shaping a legal framework that has fluctuated between democratic promise and autocratic erosion.

FOUNDING PRINCIPLES AND THE PROMISE OF PARTICIPATION

The original Constitution of Bangladesh was crafted with a profound commitment to democracy and the safeguarding of fundamental rights, aiming to foster meaningful civic engagement at its core. It envisioned a participatory polity where the people would not merely be subjects of governance but proactive participants in shaping it. The inclusion of universal suffrage highlighted this vision, granting every citizen the right to vote and participate in the democratic process regardless of class, gender, or social standing. The protection of freedom of speech and assembly further strengthened the foundation for a vibrant civil society, enabling citizens to express dissent, advocate for their rights, and organize collectively for social and political change.

The judiciary, particularly the Supreme Court, was established as a central pillar in upholding these democratic ideals. Empowered to safeguard constitutional guarantees, the Court was designed to act as a vigilant protector of citizens' rights, ensuring that the state remained answerable to the people. This institutional framework was not static; it evolved over time, particularly with the advent of Public Interest Litigation (PIL), which emerged as a revolutionary tool for promoting social justice. PIL broadened the avenues through which marginalized and disenfranchised groups could assert their rights, narrowing the gap between formal legal structures and the lived realities of vulnerable populations. In this context, the judiciary went beyond its conventional role, becoming a potential ally of the people in their quest for justice, a perspective I elaborated in my analysis of the Constitution's changing dynamics.

AMENDMENTS AND THE EROSION OF DEMOCRATIC IDEALS

The Constitution of Bangladesh, meant to reflect the people's will, has frequently been exploited by those in power, eroding democratic ideals. Its flexibility, designed for adaptation, became a tool for successive regimes to consolidate authority. Military rulers, in particular, used amendment to legitimize their rule, bypassing public participation. The Fifth Amendment (1979) under Ziaur Rahman retroactively legalized martial law Similarly, Hussain Muhammad Ershad's Eighth Amendment institutionalized religious identity, further polarizing society and straining secular foundations.

These amendments, often passed by parliaments acting as extensions of executive power, lacked public engagement, deepening the disconnect between governance and citizens. This trend culminated in the Fifteenth Amendment (2011), which abolished the caretaker government system. Ostensibly a response to judicial rulings, it was widely criticized for politicizing elections by allowing the incumbent government to oversee them. This move weakened public trust and raised fears of authoritarian consolidation, highlighting how constitutional amendments have often served power entrenchment rather than democratic progress.

JUDICIAL INTERVENTIONS: GUARDIAN OR GADFLY?

The judiciary in Bangladesh has played a paradoxical role in shaping the nation's constitutional landscape, oscillating between defending democracy and unsettling the balance of power. Landmark rulings have reinforced its role in countering authoritarian encroachments. The Supreme Court's verdict in Anwar Hossain Chowdhury v. Bangladesh (1989) reaffirmed parliamentary democracy, checking legislative and executive overreach. Similarly, the 2010 ruling striking down the Fifth Amendment sought to undo military rule's constitutional impact, restoring Bangladesh's democratic ethos.

However, judicial assertiveness has sparked controversy. The 2017 nullification of the Sixteenth Amendment, which removed Parliament's power over judicial appointments, was seen as protecting judicial independence but also raised concerns about overreach and politicization. This tension between activism and judicial restraint underscores the risks of undermining separation of powers in the pursuit of constitutional correction.

Public Interest Litigation (PIL) in Bangladesh has driven social progress, from environmental protection to minority rights, bringing vital issues to judicial attention. However, its benefits remain uneven, largely accessible to urban, educated litigants while rural communities remain excluded.

The judiciary, caught between safeguarding democracy and enabling authoritarian tendencies, plays a pivotal yet conflicted role in Bangladesh's constitutional evolution. This ongoing struggle underscores its influence in shaping democratic engagement while navigating pressures that threaten institutional integrity.

Bangladesh grapples with a stark contrast between its constitutional promises and the realities of democratic decline. Despite guarantees of fundamental rights, restrictive laws stifle free speech, enforced disappearances silence dissent, and institutions serve political interests. While weakening the constitution remains intact, selective enforcement has hollowed its spirit, democratic participation.

CONCLUSION

The Constitution of Bangladesh reflects an ongoing struggle between democratic and power dynamics. Born from the liberation war, it was meant as more than a legal framework— it was a covenant between the state and its people. However, political manipulation, authoritarian tendencies, and institutional decline have repeatedly tested this vision.

Amendments have both strengthened and weakened democracy, while judicial rulings have alternated between safeguarding sovereignty and reinforcing executive control. This tension has created a fragile constitutional order, wavering between inclusion and authoritarianism.

For the Constitution to remain a force for civic empowerment, it must be upheld through active public engagement, transparent governance, and judicial oversight. While the judiciary plays a key role, citizens must also defend democratic principles rooted in the liberation war's ideals. Only through this shared commitment can Bangladesh's constitution resist authoritarianism and foster a truly participatory democracy.

Arafat Hosen Khan, legal scholar and Visiting Senior Fellow at LSE Law School, is the author of The Constitution of Bangladesh: People, Politics, and Judicial Intervention.

Comments