In the late afternoon, the sun seemed to drift hastily towards the Phuromon hill in the west. The krishnachura leaves whispered softly in the breeze while the birds' chirping spread a melodic resonance. A festive air lingered as guests began to arrive at the Upajatio Sangskritik Institute (USAI) premises. It's August 8, 2001—the International Day of the World's Indigenous Peoples in Rangamati. But this celebration did not centre so much around the usual themes of the day as around a fashion show highlighting a vital aspect of indigenous culture—traditional clothing. The hard work of two young Chakma individuals, spanning an entire year, was about to be unveiled here. Their work brought out the tale of a cultural revolution woven into the fabric of the hills.

Every culture possesses its own distinct and defining features. It's through elements like language, literature, lifestyle, religion or belief system, cuisine, and traditional motifs and utensils that one culture stands apart from another. For the Chakma people, one such emblematic element is bain. It means the Chakma art of weaving craft of the Chakma people, representing the practice of weaving traditional wear using waist looms.

For centuries, this weaving tradition had been the aesthetic pillar of Chakma culture. Yet, this significant form of artistic expression nearly faded away under the weight of cultural hegemony and intrusion of different cultural influences.

For centuries, this weaving tradition had been the aesthetic pillar of Chakma culture. Yet, this significant form of artistic expression nearly faded away under the weight of cultural hegemony and intrusion of different cultural influences. But a few individuals, with their relentless dedication and creative initiatives, and some Chakma weavers with their tremendous mental and physical effort, revitalised this nearly lost art form, reclaiming its cultural and aesthetic splendour. Today, we will share the story of that reawakening.

The artistry of Chakma bain weaving stretches back hundreds of years. The cotton used for this craft was cultivated through the region's traditional jhum or shifting cultivation system. This cotton was so renowned that the area had once earned the name Carpus Mahal, translating roughly to 'the cotton estate'. The name was given by Mughal traders who exported the fine cotton produced in the forested hills of this region to Europe. The Chakma people's conflicts with and rebellion and war against the British centring the cotton trade are well recorded in Chakma history. The golden era of jhum cotton belongs to the past. Our ancestors had perfected the skill of extracting cotton from jhum fields, crafting eco-friendly yarn, dyeing it with natural pigments, and weaving it into garments using waist looms or bain. These looms produced every piece of traditional cloth, from the pinon-hadi and habang for women, to the jummo sulum and tenye hani for men, as well as other items like boga gamchha, borgi sheet, and aht habar. However, with the passage of time, this rich tradition had begun to fade.

Undoubtedly, this method of weaving is intricate and time-consuming. The cultivation of jhum cotton demands specific season, appropriate weather condition, and special care. Extracting yarn from this cotton is a laborious process. Dyeing the yarn with pigments collected from nature adds another layer of complexity, each step requiring careful preparation. However, the most challenging and physically taxing task is weaving the cloth using the waist loom. Through this ultimate test of physical and mental endurance, yarns are placed on intricate designs, thread by thread, and that's how each piece of fabric slowly takes shape and comes to life. In various stages from cotton cultivation to the crafting of these traditional garments, both women and men play essential roles, periodically and collectively.

A few individuals, with their relentless dedication and creative initiatives, and some Chakma weavers with their tremendous mental and physical effort, revitalised this nearly lost art form, reclaiming its cultural and aesthetic splendour.

As time passed and conditions evolved, communication systems improved in this once-isolated mountainous region. With these advancements came an influx of Bengali traders who brought with them an assortment of readily available cloth items. Even before their arrival, Bengali and some Western garments had already made their way into Chakma society, though they were limited to the Chakma Raja and a few other noble, affluent families. These clothes remained a privilege of the elite for some time. However, as these traders began to offer affordable and easily accessible clothes, they steadily gained popularity throughout Chakma society. In turn, the complex, laborious, and delicate traditional garments woven through bain gradually started to lose their relevance and utility.

The decline in the use and utility of men's traditional clothing came first. Notably, during this period, modern education was introduced among the Chakma communities, with men being the first to gain access. Those who had the opportunity to pursue this education gradually moved away from the customs and lifestyle of their forefathers, embracing a new way of living. Consequently, as part of their everyday attire, they no longer wore their traditional garments, which had suited their earlier way of life. Simultaneously, men's involvement in various stages of the weaving process diminished. This led to a decline in cotton production through jhum cultivation, and the once-thriving Carpus Mahal faded into history. The traditional knowledge of dyeing yarn with natural ingredients, a skill in which men had actively participated, also began to vanish. Thus, on the one hand, Chakma men gradually abandoned their ancestral clothing traditions and on the other, they lost touch with the wealth of cultural knowledge inherited from previous generations.

The Chakma women were an exception in that respect. They held onto their weaving heritage and traditional garments.

Sari, the customary outfit of Bengali women, increasingly became popular among Chakma women, reflecting the aggression of hegemonic cultures. Consequently, from the late 1960s to the beginning of the 21st century, most Chakma women from the educated community chose to wear saris during their weddings, gradually shifting away from their traditional attire.

Despite these changes, the bain and its unique weaving techniques endured. Behind this resilience lay a rich tradition and the efforts of countless unsung Chakma weavers, scattered across the jhum hills. Perhaps these weavers did not see the light of modern education, but they were well versed in the traditional knowledge and customs of Chakma society. Among their most prized form of knowledge was the art of weaving with the waist loom, and the most cherished custom tied to this craft was the creation of the alam. The alam is, in essence, a collection of intricate designs woven into a fabric. In those days, the ability to weave an alam was considered a key qualification for marriage, and the designs within each piece held cultural significance. Every young woman was expected to learn the methods for weaving these designs as part of her preparation for marriage. This knowledge was passed down from generation to generation, as mothers taught their daughters these intricate patterns. While the practice began to wane among the educated Chakma families at the time, it remained alive and kicking in rural communities. However, even though these women kept the weaving tradition intact, they no longer had access to the cotton and yarn once extracted from the jhum. Instead, they sustained the bain tradition using yarn sourced from the market.

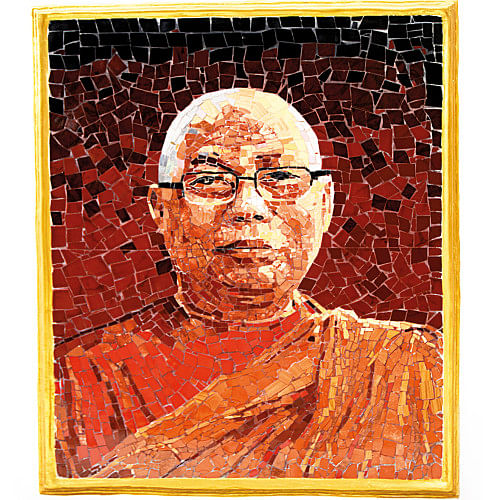

In the ongoing effort to preserve the art of bain and the traditional women's attire, pinon-hadi, within Chakma society, the contributions of certain organisations and individuals are particularly noteworthy. Foremost among them is an orphanage called Moanoghar. Three Buddhist monks had established this orphanage in the village of Rangapani, only a short distance from Rangamati city, in 1974.

One of the three monks, Bimalatishya Mahathero, aka Bimol Vante, initiated weaving activities using handlooms at Monghar in 1976. Despite his efforts, the initiative faced many challenges and did not achieve significant success at the time.

In the 1980s, however, a turning point came when Manjulika Khisa, better known as Hottali, and her mother, Panchalata Khisa, founded the 'Bain Textiles' as a private venture. This company, well recognised in the hill region to this today, was the first to produce a variety of consumer cloth items, including the traditional wear of Chakma women, using both handlooms and waist looms. Another talented weaver, Saratmala Chakma, had earned state recognition for her weaving skills and creativity since the Pakistan era. Most unfortunate was the fact that the knowledge and creativity of these talented individuals was yet to be fully utilised by the Chakma communities. Meanwhile, Bengali businessmen replicated their designs and techniques, produced garments traditionally worn by Chakma women on handlooms and sold them at lower prices. The bain, or the art of weaving on waist looms was faced with an existential crisis as a result.

Around 1997, a young woman named Arshi Dewan Roy, who had spent much of her life abroad, visited the hill regions and observed bain weaving for the first time at a relative's house. She was captivated by the technical skill and creativity of the practitioners and the aesthetic beauty of the designs. This experience sparked her interest in exploring ways to integrate this traditional weaving technique into her own work. Consequently, in 2000, she decided to focus her master's thesis on the weaving methods of all the indigenous communities living in the hills. This marked the beginning of a new phase in the renaissance of Chakma bain.

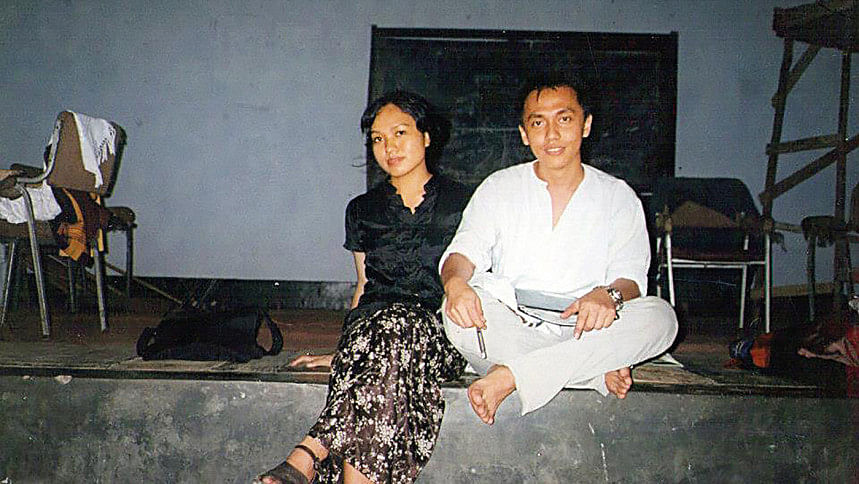

Fortunately, around that time, she met a young Chakma designer named Tenzing, who had completed a fashion design course at an institute in India and was eager to do something innovative in his homeland. This meeting was fortunate because their collaboration sparked new developments and activities in the sphere of bain.

Arshi Dewan and Tenzing Chakma's project was divided into two distinct phases. The initial phase focused on researching different aspects of bain, involving an in-depth study of the techniques and materials used by various indigenous communities of the hills. The second phase was to organise a fashion show titled Ray-gulo (Ray-gulo ,also known as Reye gulo, is a motif that is used in weaving 'pinon'. It is the original traditional motif for weaving a pinon in Chakma society), aimed at showcasing the research findings and designs they had gathered to the public. Since their work was deeply rooted in tradition, they began collaborating with individuals who had long been connected to this tradition and enriched it through the years with their talent, hard work, and creativity. They reached out to Manjulika Khisa, Panchalata Khisa, and many others, gathering information from them about their research.

Meanwhile, another significant event occurred. Arshi Dewan was introduced to a cultural organisation called the Jhum Aesthetic Council (JAC), which had long been dedicated to preserving and nurturing the cultural heritage and traditions of the various indigenous communities in the CHT. Some of the senior members of JAC were teachers at an educational institution called Moanoghar. This institution was unique in the region, offering educational opportunities to marginalised students from every indigenous community in the jhum hills. Moanoghar became an invaluable hub for the study of indigenous peoples' cultures.

Arshi met several skilled weavers from Rangapani, a village near Moanoghar. Most remarkable among them were Konabi (known as Maloti Ma), Mala, Fellabi, Sapna, Nirmola, and Shovarani. Discovering such talented weavers in the same village was a fortunate turn for the project.

Most of the weaving work was carried out with the skilled weavers from Rangapani village. First, the team gathered and organised the information, categorising it into sections based on each weaver's expertise. It is important to note that these traditional garments have distinct parts. For instance, the cloth worn by Chakma women from the waist down is called 'pinon' while the cloth from the waist up is called 'hadi'. Among the weavers, some specialise in pinon weaving, some in hadi weaving, and a few are particularly skilled in creating floral patterns and designs on both. By categorising the weavers based on their areas of strength, they effectively prepared for the fashion show called 'Ray-gulo'.

The bain process begins with collecting and preparing the yarn. The yarn is washed, starched, and dried to make badala, a type of yarn reel. These reels are then arranged serially into the structures required for pinon or hadi after suchyek and bakadi bamboo sticks are hammered into the ground. After the basic structure is set, the weaving goes through the 'fu' process. In this step, the bain structure is pushed out of the ground and the designs known as bakadi and teram are set or drawn to get the right taglak and ju. It is then the actual weaving begins. A belt called tatye cham, which is connected to the taglak bamboo, is tied around the weaver's waist, and thus the bain is prepared for weaving. After making one ju after another, the yarns are inserted into each ju and pressed with a biyong, and that's how a piece of pinon or hadi is woven, or other clothes for that matter. The weavers also carefully bring out the alam patterns—floral designs—within the cloth. Afterwards, some parts or designs from these cloth pieces were cut and combined with other clothes to create modern, trendy garments.

While the weaving work progressed, preparations for the fashion show were also in full swing. Members of JAC once again stepped in to assist, offering support from start to finish.

Now, let's move on to the final event. It was Thursday, August 9, 2001—the International Day of the World's Indigenous Peoples. The day, however, was not celebrated on a large scale back then. But it held deep significance for the Chakma and other indigenous communities of Bangladesh. From that point onwards, the indigenous peoples of Bangladesh proudly displayed their traditional attire at every event and conference.

After the success of the event, Arshi Dewan Roy returned to her workplace abroad. Her research paper was published in a journal at Concordia University in Canada. Although she could not stay closely involved with the groundbreaking work she had initiated in the early 21st century, she passed the torch to a deserving individual.

Following the event in August 2001, Tenzing Chakma launched his career as a fashion designer and entrepreneur through his fashion house and brand, Sazpadar (this Chakma word denotes instruments used in bain activities). In 2002, he organised another fashion show in collaboration with the renowned Bain Textiles. It was during this second show that the use of pinon, hadi and other garments in a variety of colours beyond the traditional palette was unveiled. Tenzing Chakma's role in popularising the vibrant and aesthetically captivating Chakma traditional attires is undeniable. His efforts earned him invitations to numerous fashion shows, both within and outside Bangladesh, allowing him to present bain of the hills creatively and aesthetically on to the global stage.

Inspired by Tenzing Chakma, there are now hundreds of women entrepreneurs and weaving artists across the hills who are revitalising the bain weaving art with their talent, creativity, and hard work. Today, hill communities proudly wear their traditional clothing at every event, showcasing a renewed sense of cultural pride. Pahari entrepreneurs have expanded the traditional alam flowery motifs and designs beyond pinon-hadi, incorporating them into various garments, including even Western-style clothing, through their refined aesthetic sensibilities.

Currently, pinon and hadi crafted by these designers are the top choice among educated Chakma women when selecting wedding dresses. Even contemporary men's wear now features woven alam patterns or designs made through the bain, reflecting the convergence of modernity with tradition. There was once a superstition in Chakma society that it was inauspicious for men to walk beneath drying women's pinons and hadis. Today, however, men wear clothes woven through bain and adorned with the same designs and motifs for pinons and hadis as those used on women's pinons and hadis. Furthermore, men wear these clothes with confidence and pride, marking a significant cultural shift.

The most groundbreaking result, however, is the empowerment of Chakma women. Take Rangapani village as an example. The women who once wove bain solely for their own use have now become the primary breadwinners of their families. The income they generate through weaving supports their households, funds their children's education, and even finances their husbands' businesses. Across the hills, hundreds of similar villages have emerged, where women are actively leading their communities' economic and social transformations through bain weaving. More importantly, the aesthetic art form, once on the brink of extinction, has now evolved into an ever-expanding industry, revitalising itself and the culture it represents.

Jidit Chakma is an anthropologist by training, and Jibak Chakma is a poet, writer, and activist.

The article was translated by Hironmoy Golder and Rifat Munim. It is reprinted with permission from 'Of Roots and Heritage: Tales from the Hills--Chakma and Tripura Communities in Bangladesh', edited by Rifat Munim and published by UNESCO Dhaka.

Comments