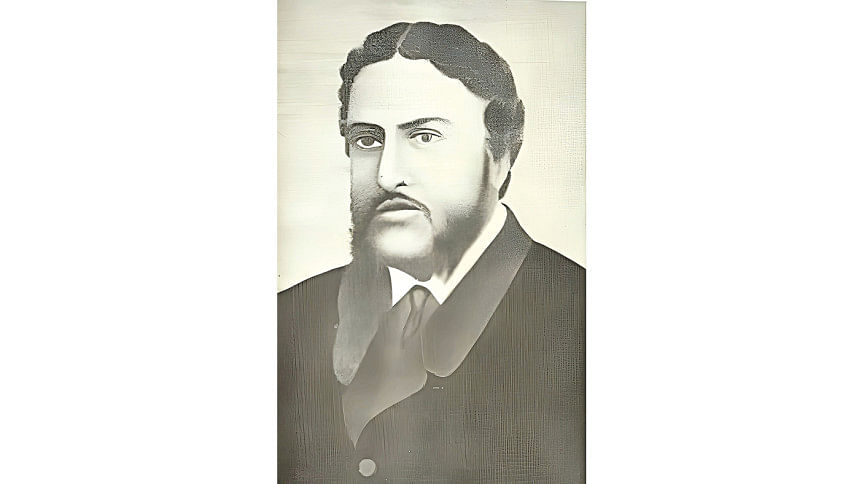

The poet and playwright Michael Madhusudan Dutta (1824–73) made no effort to conceal his disapproval of traditional Brahmin pundits. "Barren rascals", he called them, presumably pointing to their dogmatism, deep anchoring in social conservatism, and failure to move with the times. And yet, there was one man of this class with whom he made an important exception: Pundit Iswarchandra Vidyasagar (1820–91). Madhusudan called this pundit "the first man among us" — an honour usually reserved for heads of state or else a social figure of extraordinary qualities.Some of us might be misled into thinking that this was the poet's way of acknowledging the pecuniary help he often received from the pundit while struggling to make ends meet in a foreign land. Such an explanation only belittles the genius of Madhusudan, as also the selfless, humanist compassion of his benefactor. In his adult life, Vidyasagar rescued many in financial distress, none of whom, however, showered such praise on him. The irony of it all is that many beneficiaries either cheated him of his dues or else spoke ill of him in public.

Here it is also important to recall that, after some initial hesitation, Vidyasagar acknowledged the daring innovation underlying Madhusudan's use of blank verse in Bengali poetry — an act one would not ordinarily associate with a man of his class or upbringing. The Pundit, as I shall also argue, was no less an innovator himself, often defying accepted social ideas or practices. Though born a Brahmin, he cast himself in the mould of a very different order of Brahminhood, affirming the view that, in the social and cultural history of the Hindus, the Brahmin, paradoxically enough, could equally be the source of conservatism, conformity, and courageous dissent. For me, Madhusudan's exception provides valuable clues to a better understanding of Vidyasagar's prodigious life and work.

At first sight, no two men could appear more dissimilar than Madhusudan Dutta and Iswarchandra Vidyasagar. Intellectually, Madhusudan situated himself in the classicism of Greco-Roman civilisation and, by extension, in some English Romantic poets closer to his time. Socially, he coveted the life of the English gentry. Madhusudan was the son of a fairly affluent professional and received the best of modern education then available in India. He renounced his ancestral religion in favour of one he considered 'superior', usually lived beyond his means, and died a poor man.

We may also see in Vidyasagar the juxtaposition of two important agendas: first, the wider dissemination of modern public education alongside character-building; and second, a sense of social justice—the desire to speak for those, particularly women and the lower classes, who could not speak for themselves. He placed tradition and modernity not hierarchically but in a kind of kinetic relationship. In this view, tradition, rather than being fully replaced by modernity, had to co-exist with that which was arguably modern.

Vidyasagar, by comparison, was the son of a poor father, fought grinding poverty in early life, and was essentially rooted in the Sanskrit knowledge system. Apparently, he had no ambition to visit the West, even when some in the West knew of him and his work. Someone like Prime Minister Churchill may well have called him a 'naked fakir', judging by the manner in which he habitually dressed. Vidyasagar wore the cheapest and coarsest clothes — not for want of money but from an innate sense of humility and a desire to identify with the common man, as Gandhi was to do after him.

The Pundit had little or no interest in religious doctrines, preferred to socialise more with unlettered Santhals than members of his own class, even when his income from various sources well exceeded that of the average Indian. Unlike Madhusudan, he exhibited filial piety, always seeking permission from his parents before undertaking important work. On the day of his death in 1891, certain parts of Calcutta had a deserted look, with even petty traders and shopkeepers — people unconnected with the world of teaching, authorship, or publishing — shutting down their shops as a mark of respect to the departed.

What, then, led a man like Madhusudan to valorise an unpretentious and misleadingly ordinary-looking Brahmin scholar? He could see that Vidyasagar belonged to a new class of Brahmins. He was not the conservative Brahmin that the fellow educator Bhudev Mukhopadhyay (1827–94) turned out to be, nor the quasi-anglicised professional we find in a man like Bankimchandra Chattopadhyay (1838–94). On the contrary, he was, in some ways, the reincarnated model Brahmin of the old: scholarly, honest, courageous, independent, forthright, a seasoned social counsellor, and a man who respected tradition but could also suitably reinterpret it in the light of changing requirements.

Vidyasagar taught himself English and was reasonably well-read in the reigning discourse of the contemporary West. Like Rammohun Roy (1772–1833), he could cite Bacon to attack convoluted argument and dogmatism—"cobwebs of learning", as he called them—and freely admitted the superiority of contemporary Europeans in certain spheres of knowledge. Even as a Brahmin, he doubted the practical value of traditional Hindu philosophy and called the Ramayana and Mahabharata literary works, not religious texts. His was clearly a historicist view of time and tradition, not something frozen in antiquity. One may reasonably find in Vidyasagar a rare combination of humanism and humanitarianism, compassion and firmness of purpose, a willingness to learn from other peoples and cultures while remaining rooted in one's own.

We may also see in Vidyasagar the juxtaposition of two important agendas: first, the wider dissemination of modern public education alongside character-building; and second, a sense of social justice—the desire to speak for those, particularly women and the lower classes, who could not speak for themselves. He placed tradition and modernity not hierarchically but in a kind of kinetic relationship. In this view, tradition, rather than being fully replaced by modernity, had to co-exist with that which was arguably modern. Vidyasagar was himself modern in the sense that he wore many hats: he was an author, essayist, translator, publisher, printer, polemicist, philanthropist, educator, administrator, and social reformer. Perhaps such a combination of motley roles and functions did not materialise in Bengal, whether before his time or after him.

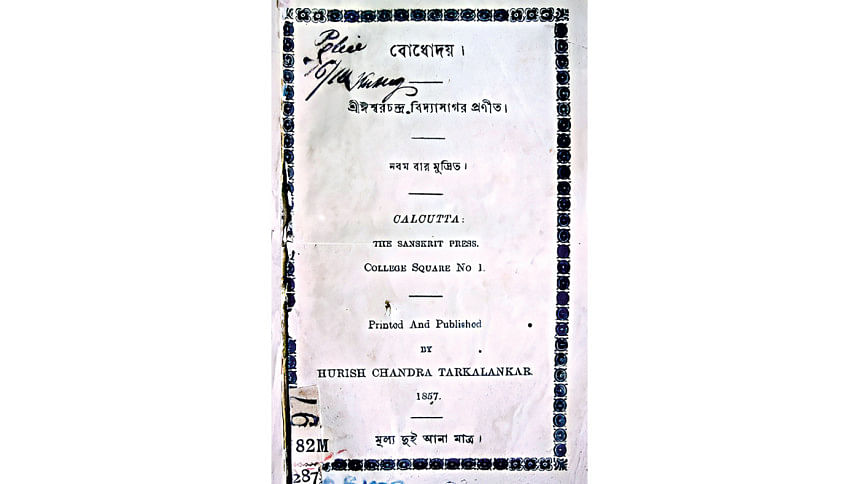

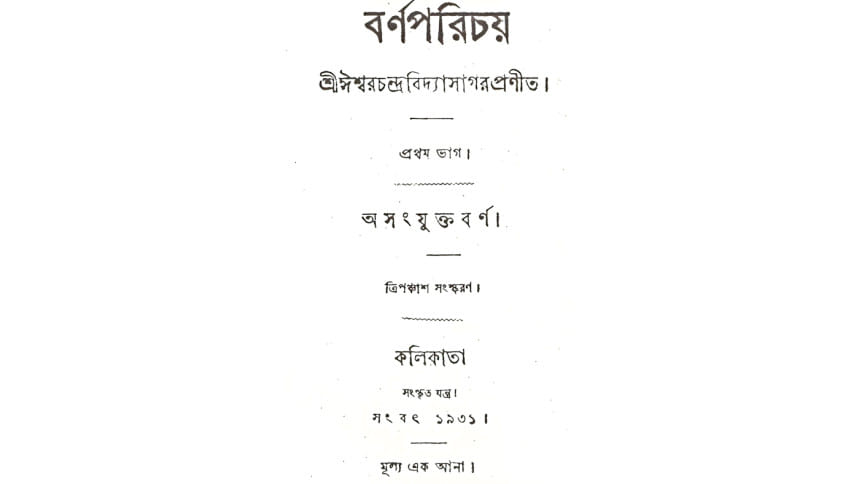

Character-building was a virtue that Vidyasagar consistently upheld in his writings, especially in his primers and school textbooks like Bodhodoy, Jeevancharit, and Charitabali. The distinctive quality about such books was the intention to instil in the average Indian student qualities he allegedly lacked: openness of mind, hard work, perseverance, but above all, the human quest to master the social and physical environment around him. In his textbooks, Vidyasagar did not valorise the docile, overly obedient, unenergetic, and unquestioning student; on the contrary, his preference was for the rebellious, hyperactive, even mischievous boy whose spirit or energy could not be suppressed by the combined weight of excessive disciplining and puerile social custom.

Not surprisingly, the pundit was critiqued both in his time and thereafter by fellow Bengalis for locating virtues only in contemporary or near-contemporary Europeans. Interestingly enough, it appears as though some of these qualities of mind that he intended for children he exhibited in his own life—never fearing opposition or reprisals from superiors and preferring self-respect to slavish acceptance of unreasonable demands. At the peak of his professional career, Vidyasagar decided to run a private school all by himself rather than give in to unjust demands made by the government. He also refused the post of professor of Sanskrit at Presidency College when the government declined to pay him the salary of a European professor.

It is in the domain of social justice that Vidyasagar made his greatest mark. While his campaigns to promote widow marriage or end polygamy are all too well known, little attention has been paid to his administrative and curricular reforms at the Calcutta Sanskrit College. On one level, his efforts aimed to make the courses simpler, more intelligible, and professionally useful. But there are certain social dimensions to such changes that cannot be overlooked.

Vidyasagar was no rebel seeking to dramatically defy or subvert Hindu society by openly violating established conventions, as was once the case with the Young Bengal group. His preference was for a more gradual but meaningful reform. Previously, only students of the Brahmin and Baidya castes were admitted to the Sanskrit College; he extended this opportunity to Kayasthas and even to the socially marginalised Subarnabaniks, Tantis, and Goalas. Quite uniquely, he also introduced courses in English at the Sanskrit College.

The pundit did not scruple to share food with non-Brahmins—much to the horror of his family and peers—had little regard for routine ritual obligations expected of Brahmins, ridiculed religious preachers, mocked Hindu ideas of the afterlife, and even disinherited his only son for impropriety.

Apart from his popularity as the author of Bengal's best-known primers, Iswarchandra Vidyasagar is best remembered for his reform efforts related to women. In truth, he was not practically very successful in these. Some regions outside Bengal saw more widow marriages than Bengal itself, and the government refused to pass a law prohibiting kulin polygamy.

On the other hand, it would be erroneous to assume that such efforts stemmed solely from the man's great compassion (karuṇā). His compassion, incidentally, extended beyond human beings: he eventually stopped using horse-drawn carriages, moved by the cruelty inflicted upon the animals. Arguably, Vidyasagar saw women as not only deserving of greater empathy and understanding, but as a class from whom men had much to learn.

In an obituary for the early modern poet Iswarchandra Gupta (1812–59), Bankimchandra rightly observed that Gupta's conservatism led him to ridicule women—preventing him from appreciating the virtues of selflessness, love, and affection that they were capable of imparting. Vidyasagar's heart cried out in anguish at the suffering, repression, and premature self-denial to which even child widows were subjected. He also worried about the moral vulnerabilities faced by unprotected widows, who were nonetheless promptly ostracised. This led him to advocate women's education and to reject premature marriage. His own daughters were married at the ages of 14 and 16—extraordinarily progressive for the time.

There was, however, one regressive side to Vidyasagar that deserves mention—if only to better assess the man and the context in which he worked. Evidently, the pundit made a fetish of the shastras. To an extent, this stemmed from tactical necessity. Had his countrymen listened to the voice of reason, social justice, or compassion, neither Rammohun Roy nor Vidyasagar would have needed to rely on shastric authority for the purpose of legislation. On the other hand, Vidyasagar eventually became a prisoner of his own strategy.

For instance, he opposed Dwarkanath Vidyabhushan's (1820–86) proposal to impose stiff penalties on men who married a second time while their first wives were still living—on the grounds that the shastras permitted such marriages under certain conditions. Reportedly, second marriages were sanctioned if the wife failed to bear a son eight years after marriage. When a critic pointed out that the fault might lie with the husband, and suggested medical examinations for both partners, Vidyasagar dismissed the objection by once again citing the shastras.

In hindsight, we may argue that Vidyasagar's life and work represent one of the two discernible trends within the so-called Bengal Renaissance: one, the rationalist, humanist, secular, and utilitarian strand; and the other, where these qualities were tempered by deep religious self-expression. Admittedly, the latter was more common, but the first had at least two stellar representatives: Iswarchandra Vidyasagar and Akshaykumar Dutta (1820–86).

Vidyasagar reminds me of the Buddha—minus the spiritual angst—and Swami Vivekananda—minus the ascetic façade. It is no coincidence that, after his own guru Sri Ramakrishna (1836–86), the man Swami Vivekananda most admired was Vidyasagar. I partly found the key to this admiration in a statement from Karma Yoga (1896), where Vivekananda asserts that a karma yogi need not believe in God or religion.

Vidyasagar was not quite an atheist, but I have a feeling he would have very much liked to be thought of in those terms.

Amiya P. Sen is a historian and currently Research Fellow at the Oxford Centre for Hindu Studies, Oxford.

Comments