"O my body, make of me always a man who questions!" — Frantz Fanon had thundered, as if pleading with flesh and sinew to refuse silence, to resist obedience. The line replays in my mind as I step into Dwip Gallery at Lalmatia on a muggy June afternoon. Outside, Dhaka swelters in its own discontents. Inside, a different humidity clings to the walls—the kind you can't blame on climate, but on accumulated thought, contradiction, and rupture. The group exhibition, which opened on 21 June under the title 'Impossible Questions', felt like a tremor beneath which Fanon himself might stir. Not questions with answers, but questions that unmake the world by merely being asked.

There are five works that gripped me—not by consensus, not by reputation, but by their noise, their silence, their refusal. Think of these not as isolated critiques, but as acts of listening to visual speech: the kind of speech that stammers, that weeps, that bites back.

I. A. Asan's Tethered Ecstasies: The Theatre of the Grotesque

The first work snarls at you. Or kisses. Or does both. A purple, dog-like beast, its lips locked with a pale, string-bound humanoid, gazes out of the canvas like a scene from a deranged fable. The colours throb: reds, violets, clay browns. Anatomical exaggerations abound, suggesting the lineage of Bacon's tortured flesh and Bhupen Khakhar's candid grotesques. But it's not merely the style that unsettles—it's the dramaturgy.

A parrot perched on a book beside a plant, a turtle politely immobile on a plate, a disused microphone, sockets, wires: all these domestic objects elevated to oracular status. Everything in the painting is either speaking or gagged, desiring or desired. The humanoid figure doesn't seem to participate in its own drama; it is performed upon. We see not a subject, but a puppet—suspended and yet eroticised, devoured by something both tender and terrifying.

Here, Lacan chuckles in the shadows. Desire, he would remind us, is never a straight line. It is not about wanting the object but about wanting the other's want. The purple beast, then, is not merely a creature but an allegory for ideology itself—desiring the subject, who is bound, silenced, yet turned on by the very gaze that subjugates. The parrot, perhaps mimicking learned speech, signals our entrance into the Symbolic Order: the realm of language and social codes. But there is no liberation here. The microphone lies silent, unused. What good is a voice if it cannot penetrate the circuitry of power?

Postmodernism and surrealism converge here not to confuse, but to accuse. Nothing is sacred, yet everything is charged. Bhupen Khakhar's influence reverberates in the humour, the queerness, and the visual perversion of intimacy. And in the background of it all, like a philosophical bassline, hums the thought of Bimal Krishna Matilal. The painting is a chaotic argument about pramāṇa, about the broken trust between perception and testimony. When language fails, all that remains is the image—and even that, it seems, has been hacked and rewired.

Byung-Chul Han's Burnout Society tells us that the subject of neoliberalism is not repressed but exhausted, not punished but self-performing. The strings are not necessarily held by another. They may be self-wound. This is not discipline but compulsive exhibition. Even pain, even surrender, must now be productive, visible, monetisable.

To stand before this work is to be implicated. We are all, perhaps, that humanoid—longing for a voice, yet erotically attached to our silencing.

II. Dhiman Sarkar's Spectral Diptych: The Veil and the Void

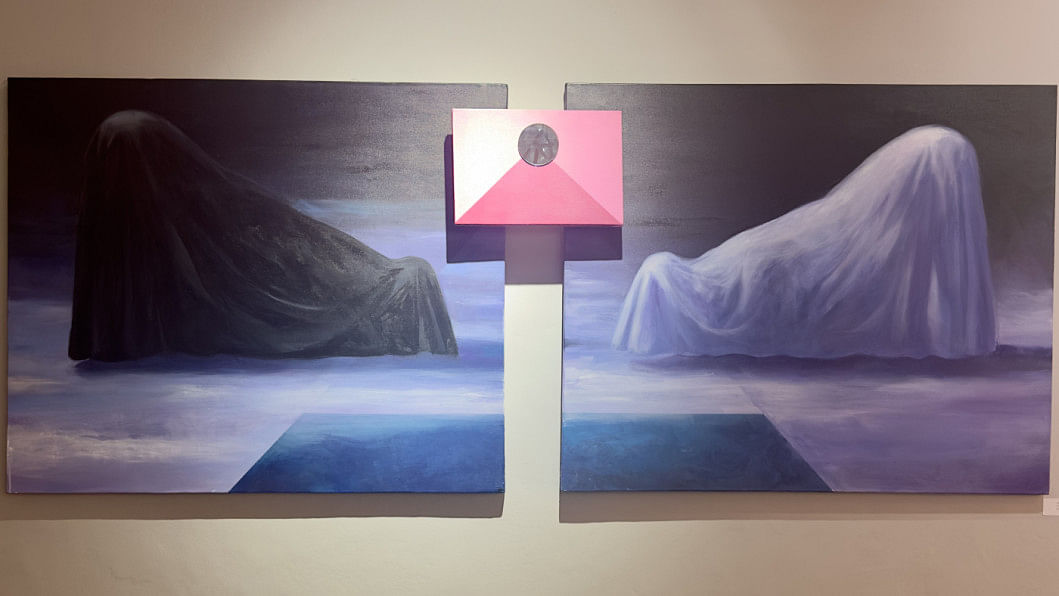

In a gallery where questions are flung like Molotovs, Sarkar's work whispers. A diptych: two reclining forms, one swathed in black, the other in white. Between them, a pink geometric obelisk adorned with a circular void. Everything is still. Everything pulses.

These are not bodies but presences. They withhold the very thing the viewer craves: recognition. In their concealment, they perform a strange generosity. The black-and-white drapery harks back to classical sculptures: Greek, Roman, Buddhist. But the symmetry here is misleading. The opposition is not binary but dialectical.

Phenomenology offers us a vocabulary. Merleau-Ponty insisted that experience is never direct—it is always veiled. And Derrida would laugh: even this veil is not a closure but a deferral. The pink monument in the centre, with its aperture, is no stable sign. It is a metaphysical peephole into absence itself. We long to assign it meaning: an eye? A womb? A wound?

And yet, we are made to linger in not-knowing.

If Lacan's first work was about excess, this one is about negation. Here, we confront the Real not through spectacle but through refusal. The veils deny us the Imaginary identification we crave. We cannot see ourselves reflected. The pink central form, like Lacan's Phallus, signifies not power but lack—the structuring absence that gives shape to desire but never fulfils it.

Here, the language of undramatic depression—the weariness that comes not from tragedy but from perpetual exposure—feels apt. These bodies may have stopped performing not in protest, but in fatigue. They are not dead; they are post-subjective. Burnt out to the point of translucency.

This diptych is a meditation on what it means to disappear gracefully, without martyrdom—a vanishing act staged not for applause, but for survival.

III. Mong Mong Shay's Fire-Flight Triptych: Myth as Machine

Three canvases. Three moods. Three climates. Mong Mong Shay's triptych unfolds like a ritual. The left burns: flesh, symbols, delirium. The centre convulses: skulls, cauldrons, sacrifice. The right floats: moons, blues, spirits at rest. This is less a painting and more a mythic diagram—a cartography of the soul's combustion.

Expressionism surges through every brushstroke. The colours are not decorative; they are operatic. The leftmost panel shows a flaming humanoid with abstract glyphs and a cosmic eye. Desire erupts in fire. Narcissus meets Kali. The middle panel is a rupture: a pot over flames, skulls encircling like ancestors or enemies. This is death not as an ending, but as transformation. The rightmost canvas exhales: ethereal beings drifting in aquamarine ether. A soft ascension. But beware of peace that comes too easily.

Jung might see a Hero's Journey: the Imaginary, the Symbolic, and the Real. Lacan would nod in agreement. The triptych performs a psychoanalytic opera. The left is ego-in-flame, devoured by its fantasies. The centre is castration—not merely sexual but ontological—the death of the mythic self. The right is the Real: unspeakable, silent, wet. Not resolution but encounter.

I read this as a karmic riddle: action, consequence, transcendence. But also, a critique of causality itself. What purifies? Who decides? The pot burns not only offerings but assumptions.

The left panel erupts in neoliberal overdrive, where productivity is not just a demand but a persona. Identity itself is measured in tasks completed, performances rendered, outputs optimised. The middle panel offers no relief—only a repackaged collapse. Breakdown becomes aesthetic, carefully curated for public consumption—a burnout made palatable through filters and captions. And the right glows with the illusion of wellness, presenting a counterfeit salvation where spirituality is marketed as a lifestyle. Transcendence is no longer an inward pursuit but a branded performance, complete with designer yoga mats and commodified calm.

The triptych is a loop, not a ladder. No transcendence here—only rebranding. Burnout disguised as awakening.

IV. Bazlur Rashid Shawon's The Ontology of Observation

In a narrow chamber haunted by green light—a womb drenched in fluorescence—we find ourselves under the eternal, unblinking gaze. Bazlur Rashid Shawon has cast us as Narcissus before the pool—except the pool is a mirror, and the reflection isn't mythic, it's digital. A CCTV eye hangs like the Eye of Horus reborn in silicon and plastic, and beneath it, a screen plays back our momentary sins: the idle glance, the selfie-snatch, the act of observation itself.

Shawon constructs a panopticon in miniature: a Foucauldian chamber of echoing reflections where we are both watcher and watched, condemned to a recursive loop of self-surveillance. The subject, caught in the act of becoming image, becomes schizoid.

We touch our phones as if to grasp ourselves, verify our being through their cool surface, but what stares back is a mediated ghost: grainy, timestamped, disembodied. There's a cruel temporality in this digital mise en abyme; the delay between action and playback renders even the present posthumous. Time is a traitor. The mirror promises identity, but the camera dismantles it, pixel by pixel.

And yet, this is not despair. This is a diagnosis. Shawon choreographs the quiet horror of modern visibility: the neurotic theatre of performance in public/private space, where desire collides with paranoia. The installation becomes a psychic confessional—a theatre of anxious self-recognition. In this cell painted with light, we are not merely observed; we become the ontology of observation. To look is to be fragmented. To see oneself seeing is to split. Surveillance here is not only political—it is psycho-spiritual. And what is the soul, if not a badly edited loop of our best attempts to look whole?

V. Shaik Faizul Rahman's Two Performers

On a twilight canvas, a myth is broken and rebuilt. Shaik Faizul Rahman presents a rat, monumentally oversized, sulking in a surreal green field, as if Kafka's Gregor Samsa has lost his insect wings and taken to the underbelly of the earth. Trapped in a red cuboid—an infernal geometry of surveillance or control. It's a rat, yes, but also more: the embodied grotesque of marginality, of class, caste, disease, and dirt.

Above it, like a god—or a satire of one—stands a figure in silhouette, poised in a balletic contortion, bow drawn, foot to head, balanced impossibly on a boulder. The tension of the archer contrasts absurdly with the vulnerability of the rat, and yet the two are stitched together by violence. Rahman is deploying symbolism with the scalpel of a political psychoanalyst. The rat is the abjected Other—Kristeva's abject given whiskers and tail—while the archer is the machinery of cultural power, aestheticised and purified into white form.

Nietzsche whispers from the background, suggesting this is the Übermensch armed not with will but with spectacle. But what if the rat is not the target, but the viewer? What if the bow is drawn at us—the supposed civilised—who watch from gallery walls, thinking ourselves above it all?

The boulder evokes Sisyphus, yes, but this one balances heroism, not burden. Yet one cannot ignore Camus' ghost, reminding us: even the absurd is a revolt. The painting tells us to "take your position", but doesn't say where. Among the rats? Or atop the mountain of power? Its ambiguity is its provocation.

Coda: The Question as Wound

To write about Impossible Questions is to write about vulnerability. These works do not answer; they haunt. They refuse coherence—coherence being a colonial virtue. Fanon's plea to his body is echoed here, not in words, but in pigment, thread, void, and flame. Each canvas says: "Look. But do not expect mercy."

These are not easy images. They do not pander, they do not explain. They demand a viewer who is willing to be scorched, bewildered, veiled. And yet, what choice do we have? As artists make visible what ideology hides, the impossible questions become necessary wounds.

As I leave Dwip, the humidity returns. But I carry something else now. A silence that isn't absence but ache. A refusal that is also an invitation. In a world addicted to answers, perhaps the only ethical gesture left is to become a body that questions, again and again and again.

Naseef Faruque Amin is a writer, screenwriter, and creative professional.

Comments