I have once faced this question: Do you ever experience depression or uncertainty after achieving a goal? The question haunted me because the answer is — yes, quite a few times. Most recently, it was when I landed my current job, which I was kind of looking forward to. But just two days in, a strange thought crept in: What's the point of all these? I felt a sheer lack of purpose. This was not the first time, but it felt especially ironic given that I had just crossed a milestone.

I kept pondering this strange emotional paradox. Why do we feel empty even after achieving what we worked so hard for? After digging through research papers, books, and essays, I realised that this satisfaction dilemma is not unique to me. In fact, it is almost universal.

We are wired to want more. We tend to believe that if I get that job, that house, or that recognition, I will finally be happy. And it does feel great—briefly. Then comes the inevitable slump, as if satisfaction has slipped through our fingers.

The sad reality about humans is that we are not wired for happiness. Natural selection prioritises survival and reproduction, which does not necessarily involve being happier. People are now less happy than they ever have been. This is not just an abstract philosophical issue; it is becoming a national concern.

A 2018–19 survey by the National Institute of Mental Health found that 17% of adults in Bangladesh suffer from mild to severe mental health issues and 13.6% of those under 18 also struggle with the same. Another 2021 study reported that 57.9% of individuals experience depression, 59.7% suffer from stress, and 33.7% deal with anxiety. These are not mere numbers, they are real people silently battling despair.

Even setting aside external sources of unhappiness, such as academic pressure, workplace stress, lack of recognition or excessive workloads, it seems that, in general, nature did not build us to be permanently content, but rather teaches us that to get satisfaction, we need to achieve more. From an evolutionary perspective, it makes sense. A constantly satisfied hunter-gatherer would not have survived. Our ancestors who always wanted more food, more security, more advantage, were more likely to thrive. Fast forward to modern life, and this insatiable drive has remained, but now, instead of lions and food shortages, we face corporate targets, social comparison, and existential confusion.

This psychological mechanism is sometimes referred to as the "hedonic treadmill." We run hard, reaching the next level, only to find that the happiness we craved was just a fleeting visitor. Researchers have pointed out that satisfaction is not simply what we have; rather, it is what we have, divided by what we want. And there lies the trap.

We obsessively work on the numerator, piling up achievements, possessions, or experiences, however, we forget to manage the denominator, our ever-expanding wants. Scholars who have spent years studying the science of happiness support this idea, emphasising that the key to lasting fulfillment lies in wanting less, rather than constantly seeking more. While this solution may seem simple, it is far from mundane.

One culprit often mentioned for our unceasing discontent is social media, the "junk food" of social life. Designed to give us momentary pleasure, it keeps us locked in a cycle of comparison and inadequacy. While scrolling through curated highlight reels of others' lives, we forget that we are only seeing a fraction of reality.

At this point, you might wonder, how do we break free? How do I practice gratitude when all I feel is emptiness? How do I find happiness when it seems like an abstract, unreachable goal?

The first step, as simple as it may sound, is to stop being a time traveler. Most of us are either regretting the past or anxiously projecting into the future. Psychologists have found that being present, fully immersed in the now, helps lower stress and boost happiness. In fact, a famous study from Harvard found that "a wandering mind is an unhappy mind." This does not mean abandoning ambition, but it means appreciating the process and what comes along the way.

Secondly, it helps to rethink what happiness actually means. Arthur Brooks, a social scientist, argues that happiness is not one thing but a combination of three: enjoyment, satisfaction, and purpose. Many of us get stuck chasing only the first, while ignoring the other two. True happiness demands aligning our actions with meaning, not just momentary pleasure.

This is where the writings of Michel de Montaigne, a 16th-century French philosopher, shed more light. Montaigne famously wrote that "the greatest thing in the world is to know how to belong to oneself." He argued that much of our unhappiness stems from being too attached to external things, achievements, possessions, even relationships, rather than nurturing inner peace. For Montaigne, happiness was not about having, but about being.

Another perspective that sounds almost pessimistic, but may actually be freeing, is the acceptance that 'nothing lasts and it doesn't matter.' It does not mean becoming indifferent, but understanding that every feeling is a passing cloud, not the sky itself.

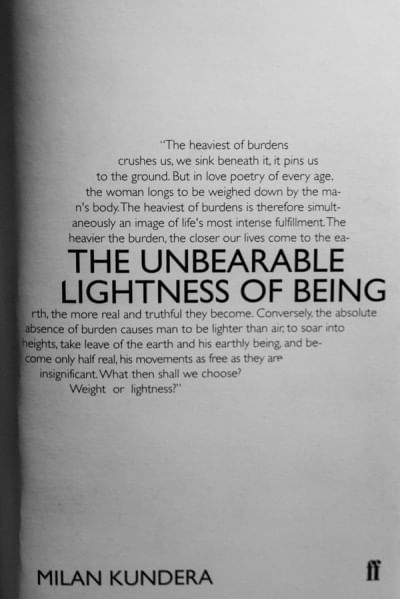

Czech novelist Milan Kundera explores a similar philosophy in his most renowned book, The Unbearable Lightness of Being, that life is fleeting and without inherent meaning. The transient nature of emotions and experiences echoes this notion that nothing is permanent — not joy, not sorrow, nor anxiety.

In this sense, everything in life can feel light because nothing lasts forever, and this lack of permanence can either be liberating or burdensome. However, the recognition of the fleeting nature of life and emotions allows one to detach without feeling overwhelmed by them.

Finally, it is difficult to practice gratitude when life feels overwhelming. Yet, research consistently shows that actively practicing gratitude, even listing three small things you are thankful for daily, rewires the brain for positivity over time. It is not a miracle cure, but a quiet rebellion against the culture of perpetual dissatisfaction.

So where does that leave us? Maybe, the secret to lasting happiness is not about constantly climbing to the next goal. Perhaps it is about stepping off the treadmill, embracing the impermanence of things, and learning, as Montaigne would say, to "belong to oneself."

Miftahul Jannat is a journalist at The Daily Star. She is drawn to philosophy and the quiet puzzles of human emotion and writes to make sense of the questions that refuse easy answer.

Comments