SONADIA

Cox's Bazar sludge flowing into the sea smelt terrible.

Our speedboat revved and took a sharp turn through the black sewage. It flashed past the wooden fishing trawlers moored haphazardly. The fishermen were lazing on the deck after the night's catch. They looked at us uninterestedly.

In two minute's time, the channel water turned green. The morning light caught the continuous water flowing through the cooling chambers of the ice factories by the shore.

In another few minutes, the signs of township disappeared and we were heading straight towards the Sonadia Island.

The morning light was washing over the shores, the long grasses burned emerald, and we pushed on. Above us was the deep blue sky. The cool morning breeze lashed our faces. We shivered in cold and excitement.

We were still on the channel and the children basking in the sun by the bank waved at us.

Before we took the final purge out of the channel into the open sea, we saw this big flock of Asian Openbill Storks. Over twenty of these huge birds were picking on snails and clams on the shore. We passed very close to them. But they would not even cringe. In this morning light, the shore was all theirs.

Now we were out on the sea. I checked my clock; it took us about 10 minutes to cross the channel. Just then the hump of an island came into view.

“That's also Sonadia,” Sayam said. “The speedboat men bring tourists here.”

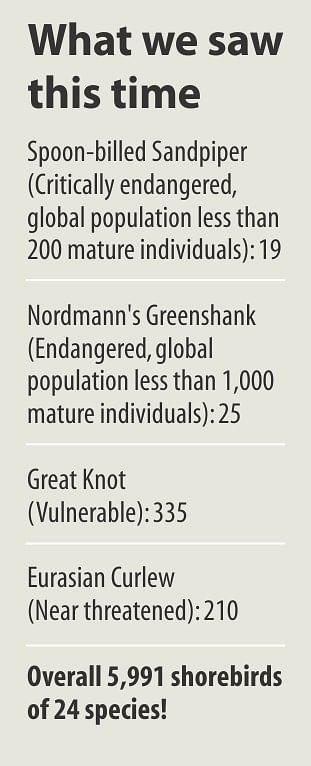

But our destination was much deeper into the sea, to the remotest part of Sonadia. With luck we would be able to see one of the rarest and critically endangered birds in the world -- the Spoon-billed Sandpiper. Worldwide there are fewer than 200 of this bird surviving and the number is going down fast.

Sayam U Chowdhury is a young ornithologist working to save this bird from global extinction. He runs a small scheme called Bangladesh Spoon-billed Sandpiper Conservation Project (BSCP) with small support from several international conservation organisations.

It was Sayam who put it into my mind to go and have a look at this wonderful island where one gets to see the largest population of this bird.

But that is not the only incentive for me. Sonadia is actually a spectacular place for any bird watcher. Name any shore bird and you are sure to find one there at one time or another as we discovered later.

For now our speedboat was slicing through the sea. We could see the strange formation of the continental shelf. The sea as we know it should have been something deep and vast. Here it is not. So much silt has rolled down from the Himalayas that the sea bed at places has become so high that our boat had to detour to avoid being stuck in the middle of the sea. We could look down the clear water and see the sandy seabed.

Then we saw about 40 fishing boats standing still on the water. The fishermen had spread wide a net not less than a few kilometers long.

A small patch of land has surfaced there. A fishing boat had moored and the fishermen were unloading the catch.

Before all that we first saw the streaks and dots of white. Hundreds of gulls had converged on the brown sandy beach. As the fishermen sorted the fish, tossing away the "unimportant" fish from the buckets, the gulls had a good feast.

We took a short break there and then pushed on. The sun was now casting a soft glow over the sea, turning it red. Another 15 minutes on the boat and then the scene started changing.

We were now coming close to the place we want to get down. There were islands around us with thick green mangrove forest.

This is a superb job done by the forest department. It has created a mangrove forest on the islands. This serves quite a few purposes. For example, mangroves are important for shrimps fawning and biodiversity. But planting mangroves on mudflats where shorebirds feed would be unwise.

We passed through a narrow channel and the Keora and Garan trees made the place look like the Sundarbans. One could easily get confused if brought down here blindfolded.

We parked our speedboat here and went ashore. The beach here has its own character that serves to support shore birds, specially the spoon-billed sandpipers. It is sandy with a very thin crust of mud. This helps the birds walk around easily and fed on invertebrates.

Birds in their thousands were flying around us. We set up the spotting scope and peek through the lens. There were godwits in their hundreds. And plovers of all kinds in their thousands. These funny looking birds will make anyone laugh with their cartoonish expressions.

The big curlews were poking their long curved beaks deep into the sand in search of food. The whimbrels were having a break from morning feast. The turnstones ran around in comical steps. But no spoon-billed sandpipers.

We moved on to another flock. After ten minutes' search, we saw it. The beautiful little bird with its telltale spoon-shaped bill was basking in the sun. It already had its breakfast and so it was time to prune and rest and maybe wonder about its own existence. It displayed its spoon in the most graceful way.

There were more in the crowd. That day we counted a total of 19. Not a bad record considering there are only about 200 left in the world.

When it gets freezing in Siberia, these birds travel about 7,000km each year to Bangladesh, their final destination. On the way they touch down at Japan, Korea, Vietnam and Myanmar. The last stoppage proves to be fatal for them as many of them get killed by the hunters, a major reason for their dwindling number.

Their presence in Bangladesh was first discovered in early 1980s when 209 of them were spotted during a water bird survey. A few years later, they were found trotting the beach at Patenga. It was birder Ronald Halder who first filmed the bird in Bangladesh.

By the time the winter ends, the sandpipers will fatten up and fly back to Siberia to lay eggs. They usually lay four eggs, but only about half of them survive.

By now the sun was above our head and the tides were rising. The island was transforming fast. The Keoras and Gorans were slowly being submerged. So were the small dunes where the birds were roosting. Some of them completely went under water and the birds took off for some higher grounds.

We walked back to our speedboat. On the way we saw some dead Olive Ridley's Turtles and horseshoe crabs. These turtles get entangled with in the fishermen's nets and die. They are globally vulnerable and fortunately we get to see them on our coasts. But they get killed either by the fishermen or by stray dogs when they swim ashore to lay eggs. There is very little effort to save them in Bangladesh.

Our next stoppage was another island also part of Sonadia. Here we met a party of crab catchers. The poor men in tattered dresses were having their lunch -- a big bowl of rice and lots of red hot crab curry.

A curiosity rose in me. A deep-sea port is going to be built at Sonadia and it has already raised a huge concern among environmentalists because it is a place for at least six endangered species, including the spoon-billed sandpiper. Geo-engineering will be needed to build the port that may hurt fishing as well. So I wanted to know if these crab catchers are aware of the possible threat.

Montu Das was the pack leader.

“Oh, we are waiting eagerly for the port,” he said. “The port will mean job for us. I don't want this hard profession anymore.”

Of course he doesn't. Because yesterday this party of six people caught only 2kgs of crabs and sold for Tk 200 only.

But they do not know if fishing will be the same after the port is built. And nobody can predict what will happen to the amazing biodiversity of Sonadia.

We then went to another island, Ghatibhanga. It's a large fishermen's colony and the pungent smell of dried fish hangs heavily in the air.

Here we met Muslim Mia at his small tailoring shop. Muslim is one of the 25 bird hunters identified by Sayam. They would regularly lay out traps and catch the shorebirds. Spoon-billed sandpipers were their victims too.

The hunters were provided with funds for alternative livelihood with the promise that they would not hunt again and that they would stop other hunters. The scheme is working, at least until now, and hunting has stopped.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments