While the fetal clock develops, mom’s behaviour tells the time

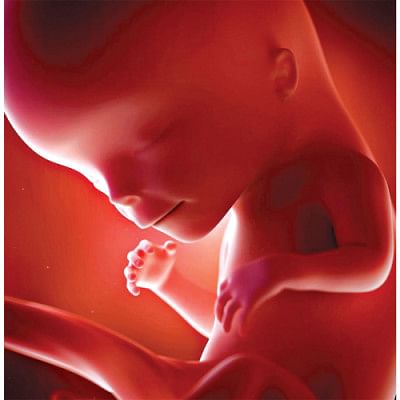

During foetal development, before the biological clock starts ticking on its own, genes respond to rhythmic behaviour in the mother. The hypothalamus's suprachiasmatic nuclei (SCN) are the body's timekeepers. Rhythmic gene activity in SCN cells governs the activity of many other genes locally and throughout the body, influencing circadian rhythmic behaviour such as feeding and sleeping. But rhythmic gene activity begins late in foetal development, raising the question of whether maternal influences entrain SCN gene activity before birth.

The authors compared gene activity in SCN tissue from pregnant rats kept in the dark under two conditions. Lesioned rats had disrupted SCNs and limited food access to impose a circadian rhythm in their activity that their SCNs could not sustain. Control rats had intact SCNs and free access to food.

They found that, within the SCNs of both sets of fetuses, there was a very small set of genes whose timing patterns differed between the two groups and a much larger set whose activity oscillated in sync with each other.

The study reveals that distinct maternal signals rhythmically control a variety of neuronal processes in the fetal rat suprachiasmatic nuclei before they begin to operate as the central circadian clock. The results indicate the importance of a well-functioning maternal biological clock in providing a rhythmic environment during fetal brain development.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments