Scaling Mount Saramati

We reached Pungro, a small town in northern Nagaland's Kiphire district, late at night after covering about three and a half hundred kilometres on a dusty, winding mountain road. With no lodges available, the car driver took us to a government rest house. However, as foreigners from Bangladesh, we were told we needed permission from the zone's additional district commissioner.

Despite my scepticism about disturbing a high-ranking official at such a late hour, we had no other options. I climbed a nearby hill with the caretaker to the ADC's bungalow. The caretaker briefed the official, a young and friendly ADC who, with a welcoming smile, inquired about our travel plans. When we expressed our desire to explore Nagaland's highest peak, Mount Saramati, he permitted us to stay at the rest house for as long as we wanted.

Our journey began on January 20 from Dhaka at dawn. After crossing the Bangladesh-India border at Akhaura, I and my two travel partners, took a domestic flight from Agartala to Guwahati to catch the late-night train to Dimapur, the gateway of Nagaland. After a night-long journey, we reached Dimapur at 6:00am. Then we took a four-wheeler to Pungro.

The next day, we decided to stay at Pungro. After such a long and bumpy drive from Dimapur, our tortured bones wanted some rest.

However, a big surprise awaited us when we went to the police station for permission to go to Thanamir, a small frontier village bordering Myanmar, the last human settlement for trekkers to Mount Saramati.

Heading there seemed challenging. We wanted to visit a turbulent border area where the rebel Naga Army had a camp. This region is notorious for insurgency.

After hearing about our objective to climb Mount Saramati, the police officer quietly left the premises with our passports. While we were waiting anxiously, he copied all of our documents and arranged all the necessary official and unofficial clearances. Who thought such an officer existed in this world!

With the permission of police chief, there was no more uncertainty. By night, we reached Thanamir.

Thanamir has gained quite a reputation as the apple village of Nagaland over the years. We had decided to rest here for another day. It was an opportunity to learn about Nagamese customs.

Land ownership in Nagaland is different from ours. Most of the land in Nagaland is owned by villages. Reserve forests mostly occupy the few areas under government control. The lands that fall under the villages could be divided into two parts -- the larger part is reserved for forest, and the lesser part is used for cultivation.

The people of Nagaland, like our people of the hills, practice jhum farming. After three to four years of cultivation on each hillside, the same land is again used for jhum after five to six years. Along with rice and other crops, seeds of nitrogen-restoring plants are also sown which helps to restore the quality of the land.

The Nagamese tribes are no longer migratory. They no longer have to cut down new forests for fertile farming land. The best part of their practices was that they did not touch the riparian forest on either side of any stream. I did not witness any dried-up streams there in January.

I noticed that rainwater harvesting was a top priority. Each jhum field contained a small pond to retain water, which the villagers used for irrigation during the summer months. The traditional slash-and-burn style jhum cultivation in Thanamir has significantly decreased, with many arable lands now being converted to apple orchards.

The following day, at dawn, we left Thanamir village to head towards the base camp of Mount Saramati. After some time, we entered a dense forest. The trail leads to Saramati through all the giant trees. At one point, the uphill began. We thought the trails here would be similar to Bandarban's. But in no time, our perception changed. No trail in Bandarban has such frequent uphill climbs. The trail had steep ascents followed by sharp descents, resembling an ECG. And there was no single source of water along the route. It took us about 7 hours to reach the base camp from the village.

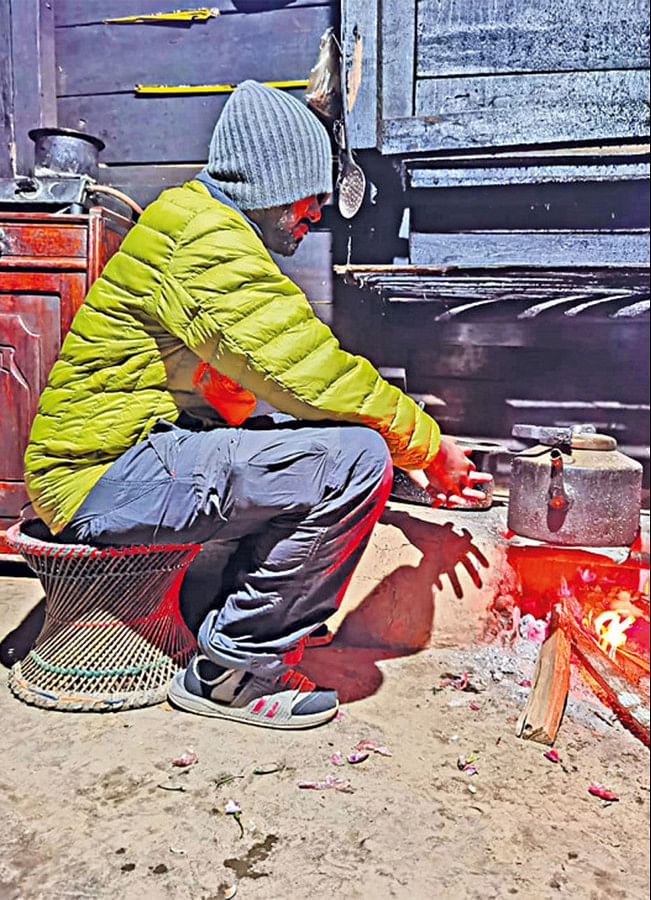

At the base camp, there were two wooden houses -- the small one used as a kitchen where the guides and porters also sleep and the larger one for the guests. We had dinner with daal, rice, and extra-spiced canned tuna.

After a strenuous day of hiking, our bodies needed rest, though we had little time for sleep. We planned to depart for the summit at 2:00 am.

Eventually, it was three o'clock in the morning when we left for the summit. We started our climb under the watchful eyes of the stars. It was a bit windy, but nothing alarming.

Mount Saramati is the highest peak in Nagaland rising above the surrounding mountains. The elevation of this peak is 3841 meters above the sea level. It is one of the prominent peaks of the Arakan Yoma range. It is situated at the junction between Naga Hills and Patkai Hills.

After hiking for a while, we entered a rhododendron forest. Patches of snow had accumulated throughout the forest. At one point, we found the ridgeline.

This mountain arc is very much like the Alpine region. After three thousand meters, no big trees can grow here because of the wind. Only some bushes and grass grow on the surface of this mountain. It also acts as a barrier, cutting off the southwestern monsoon clouds from Myanmar.

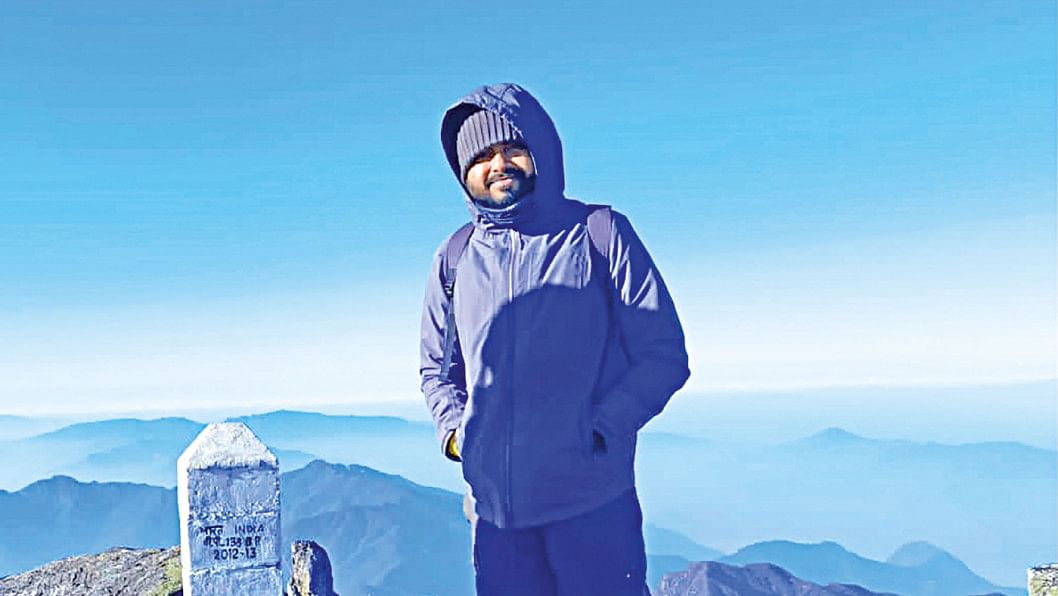

Then, all of a sudden, the storm started. The wind was so strong that it seemed to blow us away to Myanmar. Some parts of the ridgeline were quite dangerous due to strong winds. Having crossed those places very carefully, we, the Bangladeshi team of Salehin Arshady, Abdullah Alamin, and Ashraful Haque, reached the summit on January 27 at 7:00am, becoming the first Bangladeshis to do so.

In the south, I could see the tops of neighbouring mountain peaks floating in the sea of clouds. I could not believe my eyes. I was finally witnessing the eastern wall of the Indian subcontinent, the great Arakan Yoma.

The Arakan Yoma runs from Cape Negrais in the south into Manipur, India in the north. They include the Naga Hills, the Chin Hills, and the Patkai range which includes the Lushai Hills. The mountain chain is submerged in the Bay of Bengal for a long stretch and emerges again in the form of the Andaman and Nicobar Islands.

So, technically, if I could traverse all these mountains one after another, I would end up in the Andaman and Nicobar Islands!

Who knows, it could be my next adventure.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments