Scaling Mount Whitney

"My God! How can a mountain change so much in just a month?"

Standing just below the summit of Mt. Whitney in the Sierra, I couldn't help but wonder if this was the mountain I had researched for hours.

It was late, almost evening. The early December sun in the west was setting quickly as if it was in a race. I stood alone halfway up an icy slope, panting heavily. A gust of brutally cold, dry winter air slashed my face like a sharp knife as I looked up. The summit of Mt. Whitney in the great Sierra was just about a hundred feet away, the last pitch before the top. My lips and throat felt as dry as desert sands, desperately craving a sip of water. But alas, all I had in my insulated, thermal bottle were ice clusters – the negative thirty-degree Celsius temperature was too much for the bottle to keep the water in its liquid form.

"Just a little more, just a few minutes to the top," I tried to motivate myself. Alone in that ethereal environment, I couldn't help but remember what brought me there.

For some time, I wanted to add the experience of a winter solo climb to my repertoire, and my eyes fixed on Mt. Whitney for a couple of reasons. First and foremost, the magnificent Sierra Nevada -- the mountain range home to this peak. "There's nothing like the Sierra," the words from the legendary mountaineer John Muir had been playing in the back of my mind for quite a while, and I was keen to explore those incredible mountains.

The thought of attempting Mt. Whitney, the highest peak (14,497 feet) in the continental US (excluding Alaska), as my first winter solo, was quite appealing.

Another reason was the beauty of the trail leading to the basecamp and the relatively low technicality of the climb under normal conditions. Though the trail is around 34 kilometres long, the actual climb is non-technical in its normal climbing season until late October.

After that, the snowfall starts and the trail gets buried under tonnes of winter snow, raising the difficulties of the climb significantly. The winter climb requires proper gear and preparation to survive in the extreme cold. Finding a route through the white ice becomes a daunting challenge.

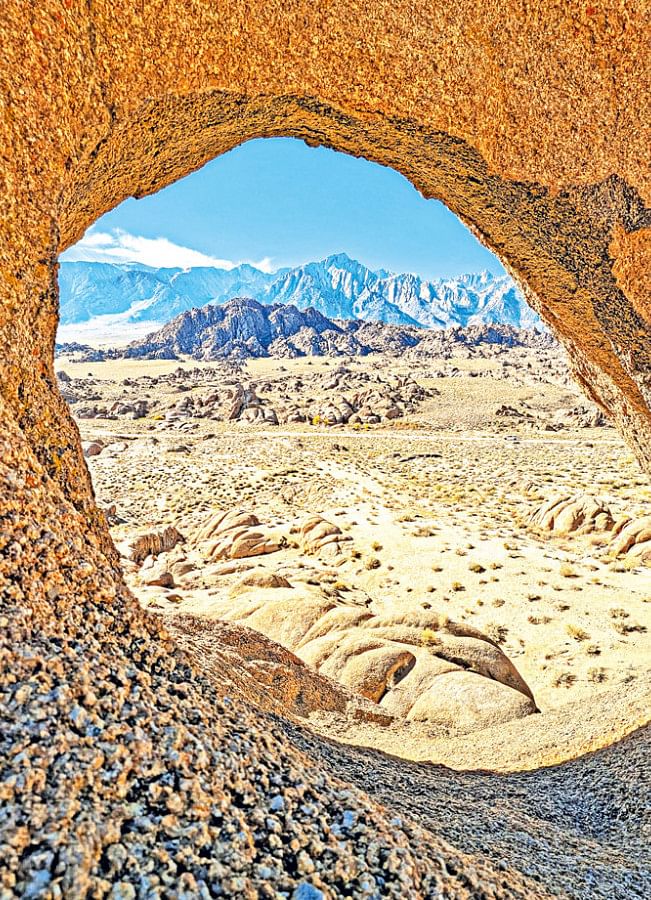

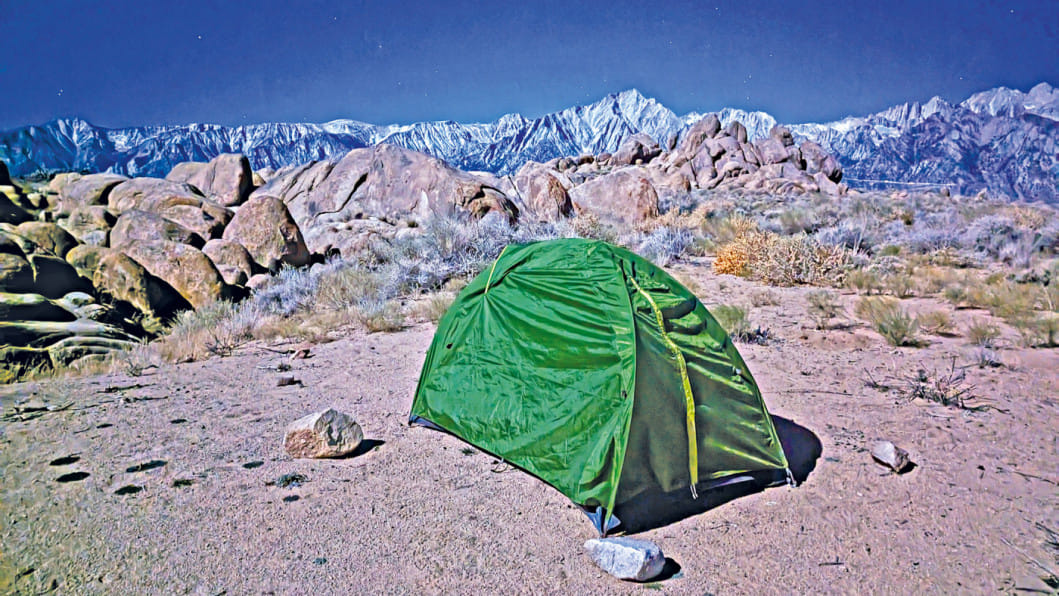

Winter arrives in the Sierra Nevada around mid to late November, so I set my plan in motion following the Thanksgiving holidays. After flying to Nevada, I drove to the Alabama Hills, a picturesque desert nestled in the Sierra foothills. I camped overnight there to acclimate and started my hike from the trailhead the next day around 11:00am. With the vast distance ahead, the plan was to cover at least a third of the distance and establish a basecamp for shelter against the biting cold wind. The trail quickly steepened, soon disappearing beneath soft layers of snow that hardened as elevation increased, obscuring any discernible path. Not many people climb in the Sierra during winter, so there was not much beta data to know what to expect beforehand. As I neared my probable basecamp, the plummeting afternoon temperature, the almost frozen lakes, and the amount of snow on everything made me realize that it was going to be a lot tougher than I thought.

After setting up my campsite at a good spot protected by a big boulder, I cooked, had my meal, and went to sleep early. The wind intensity and the harsh cold increased ferociously with time. Though I had prepared my sleeping system well for the extreme cold at night, it still felt too much at times. The sleep was erratic, and as a result, I woke up about three hours late. Instead of my planned 3:00 am start, it was now 6:30 am when I finally left my campsite for the summit push with a 10.5-kilometer distance and a 4,500-foot elevation gain ahead.

I took my first break at Consultation Lake after a couple of hours to have my peanut butter-chocolate sandwich. Soon, I realised that the thermal water bottle I had was no match for this extreme cold as the water started to freeze inside the bottle. I looked around; the large lake was completely frozen, and it was certain that no water source would be available throughout the climb to refill my bottle. So, if my water froze, I wouldn't have any other option except to crush that ice with the pointy end of my ice axe and chew on it!

Despite being a bit frustrated, I decided to move forward. After a short while, I reached the notorious "99 switchbacks" section where the trail became extremely dangerous as it steeply traversed the mountain, and there were places where a slip could be fatal. What began as a strenuous uphill snow hike had become a formidable test of endurance and skill amidst frozen landscapes and treacherous conditions. Negotiating through snow, rock, and ice demanded expert route-finding and the fortitude to withstand extreme cold and furious wind gusts – a true testament to the resilience required for a winter ascent.

Time was flying by, and in contrast, I was advancing at a sloth-like pace with a constant feeling of dehydration and the fear of altitude sickness that comes with it. It was late afternoon when I got a clear view of the summit, which was still about an hour away by my estimation. Though the weather was pretty good with a blue, clear sky and still some warm sunlight left, I knew the temperature would drop at least ten degrees more just after sunset. I hastily moved forward and soon stumbled upon the last pitch – fifty meters of an icy section just before the summit.

What would be just boulder-hopping in normal conditions was now under feet of solid, slippery snow. I looked at the slope – it did not look good with its formidable gradient. I was using microspikes, a traction device similar to crampons but not as good as the actual ones, so I could not be very secure about footing on that slippery ice. It would have to be one step – strike the axe into the ice – pull the body up using the axe – another step – and repeat probably a hundred more times. It was surely going to be a tough, tiring climb!

As every nightmare ended, that pitch was over just a few minutes before sunset. I reached the top, ate a few Oreo cookies I had with me, chewed some of those ice clusters again to keep myself hydrated, and experienced one of the best sunset views of my life. It was a surreal moment – summiting the highest peak of the incredible Sierra in those winter conditions, finding myself way above all the clouds with the grand panoramic view of this marvellous range, and witnessing the last rays of the sun over the region before it set.

But I had to climb down quickly reigning in all emotions as it would be dangerous to climb down that last pitch in the dark.

As expected, the night was even colder, and I had to keep moving constantly because my body started to freeze every time I stopped for a second. But I still couldn't resist stopping to marvel at the epic scenery of the moonlit mountains.

My God! It was undoubtedly the most wonderful moonlit night I have ever witnessed.

Despite the breathtaking beauty, I was climbing down swiftly, almost running, thanks to the slope and gravity. It took just half the time to reach my basecamp compared to the ascent, and "Ah, peace!" I exclaimed loudly, drinking the "liquid" water after almost a day.

So yes, it was a ten-hour long push to reach the summit, and another five to come down. I was exhausted and heavily drained; it felt like every system in my body was frozen, and my lips and face were dried and burning from the extremely cold, biting wind. All twenty fingers felt almost numb all day, even after wearing Gore-Tex gloves, boots, and layering with multiple socks. I was constantly worried about getting frostbite. But still, the wonderful feeling of standing on top of the majestic Sierra Nevada, the mesmerizing beauty of the sunset and moonlit mountains, and the adrenaline rush – nothing could beat that combination.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments