On wars and words

Karar oi louho kopat

Bhenge fel kor re lopat rokto-jomat

Shikol pujar pashan-bedi!

I was about seven or eight years old when I first heard these lines sung in the boisterous chorus of the little boys from my class as our music teacher played the harmonium in preparation of a Victory Day cultural program. I couldn't comprehend a single word being uttered—and yet it sounded like a warcry. And yet, I felt something rise up in me: a kindling fire, a burning spirit, a scorching desire to seize something. Generally, the fervour invoked by this lyric penned by bidrohi kobi Nazrul is attributed to the musical beat of the song and its fast-paced tempo. However, with whatever knowledge of poetic metre and phonetics I have now, I can trace some credit to the frequent usage of plosives like /k/, /p/, and /t/ as well as the rapid back and forth between the trochaic and iambic metres. Read or sung as per the maestro's intended rhythm, it sounds like an organised chaos. And I think that's exactly what wars are—organised chaos.

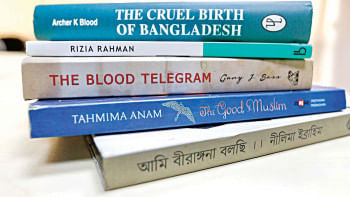

My nana-nanu are freedom fighters. Being close with nanu, the muktijuddho felt like an integral part of my identity growing up. For the purpose of this article, I sat down before her, held her hands and implored her to tell me about the details she remembered of the words that kept her and nanabhai going in such times—through the onslaught of fear-mongering military threats and raids. I could feel the delicate bones beneath her soft skin, cold to touch, as she recalled the loudspeakers blaring "Amar shonar Bangla" at her village in Manikganj. She recalled how the words of the song filled her with a sense of pride for her mother tongue, for those martyred by the love of it in 1952, and for the likes of her belated husband, who were continuing to fight for its freedom. She recalled how nanabhai had echoed the same thoughts and feelings to her while recounting his guerilla training at the Dehradun camp.

From what I hear from my nanu, who is a freedom fighter, the most iconic lyricism that reigns the Victory Day celebrations in our country and what I can piece together as a Bangladeshi citizen perceiving the muktijuddho from the distance of time, is that the glorification of soldiers and their efforts asserts a dominant presence over all other themes of war. It is a sentiment echoed in the odes of Horace: "dulce et decorum est pro patria mori," i.e. it's sweet and proper to die for one's country. "Dulce et Decorum est" says the title of Wilfred Owen's famous war poem—but this time, more ironically so, as Owen strips the glory and glamour attached to a soldier's valour to expose the gore and grime of its reality: "Men marched asleep. Many had lost their boots, /But limped on, blood-shod. All went lame; all blind; /Drunk with fatigue; deaf even to the hoots /Of gas-shells dropping softly behind." And this is not even the goriest of the images that Owen paints with his words. Reading what the poisonous gas does to the soldier that falls short of time to put his gas mask on would easily arise revulsion and horror in any reader; and Owen contrasts that very horrid image with only two simple words underscoring how behind those visions of violence lies a blameless happenstance: "Of vile, incurable sores on innocent tongues,—". With just two words, Owen makes the reader reconsider the person behind the propaganda-inspired grandeur of a soldier's image. It's just an ordinary man; it's just someone as inconsequential to the grand schemes of the organised chaos of wars as your brother or the neighbour's teenage son.

The hollow feeling I get from this epiphany is very similar to the effect created by the words of poet Shamsur Rahman in the opening lines of his poem "Asader Shirt". The disparity between the blood stains on Asad's shirt and what they're metaphorised as (the red of typically beautiful things like oleanders and sunsets) births a chilling irony. And yet, that same air of glorification presides over the images of horror. When I contrast this against the similar techniques of Mahmoud Darwish in "A Soldier Dreams of White Lilies", the effect is markedly different, perhaps because Darwish's soldier belongs to the opposition and his stoic commitment to the atrocities of war does not warrant any sympathy. Nevertheless, Darwish still manages to humanise this soldier with his longing for the softer things in life—"[his] mother's coffee," "lemon flowers" and of course, "white lilies." The polarising effects created by Darwish's contrasting imageries of war and the soldier's dreams are exactly what makes this poem, in my opinion as a thinking observer of wars, so praiseworthy in its intent. Because wars are never one-sided, thus their victims aren't always just the oppressed but often the oppressor too—particularly the hands that commit its carnage directly—as apparent from Darwish's soldier dreaming about a life of safety ("Homeland for him, he said, is to … return safely, /at nightfall").

With that, when I come back to questioning why the words of the war poems and lyrics dominating the muktijuddho's narrative, in spite of all its vigour and evocativeness, feels overarchingly one dimensional in its tones of glorification—I finally realise that it is rightfully so. And why not? These words are not just some veils adorning the valour and victory of our freedom fighters; they're not just tributes but testaments to the rare occasion of the oppressed overpowering the oppressor. These words are powerful. But why is it so important for these words to be of poesy or musical lyricism? Because speech is ephemeral; because stories get corrupted by the passage of time (ref: the telephone game, folklore, history texts). But poems and songs are much more eternal. And yet there's more: I recall my index finger breaking its monotone of swiping up each reel on my Instagram feed as my attention is captured by the resonant voice of a boy—a child—reading out his poetry to an audience of hundreds of protesters, an open-letter where he apologises to his friend at Gaza over the guilt of a privileged life. I feel the ghost of a memory rekindling something. I recall my poet friend, Raian Abedin, praising Ilya Kaminsky's "We Lived Happily During the War." I read it and feel the dwindling flames in me fanned by a gust of shame and guilt. I recall Asad uncle, a distant relative and beloved mentor, recounting to me how he had sneaked out from home at the age of 19 to fight for freedom; how he would listen to Hemanta Mukherjee's "Maago Tomar Bhabna Keno" at the military training camp and simultaneously shed tears for a glimpse of his mother while trying to harden his heart for whatever reality had in store for him. To this, I feel the flame in me give out with a sigh tinged in shades of blue.

All this is to essentially say that the words of verse are far more efficient in terms of the emotions they elicit. I am thinking of Shamsur Rahman's "Shadhinota Tumi" and the lyrics of Gobinda Halder's "ek shagor rokter binimoye Banglar shadhinota anle jara, amra tomader bhulbo na" as I'm writing this—and I'm thinking of how these verses help me reconcile with my national identity more intimately than any amount of textbook knowledge of the muktijuddho ever could. I am thinking of Rupi Kaur's moving words penned in tribute to a fellow belated Palestinian poet. I am thinking of the language of resistance in the verses of Anna Akhmatova, much more subdued but just as effective as Kazi Nazrul Islam; of the poetic prowess of Bangabandhu's 7th March speech; of the language of protest in placards saying "from the river to the sea, Palestine will be free"; and of Instagram reels exposing the Zionist terrorism. Ultimately, my deconstruction of national and international war poetry reconstructed into slices of epiphanies has helped me to arrive at this one conclusion: that words hold the power to wage wars much stronger than any weapons, depending upon how well we weld and wield them.

Tashfia Ahmed is a writer and poet who teaches English at Scholastica School.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments