Abuse behind the closed doors of madrasas

Jahid (not his real name), a nine-year-old boy from Mohammadpur of Magura district, was admitted to Panihata Hafizia madrasa by his father Abdul Aziz. He wanted to make his son a hafiz, a person who memorises the entire Holy Quran. Unfortunately, his only son is now under treatment in Mymensingh Medical College Hospital. Jahid has been groaning in pain and cannot even fully recognise his parents due to the traumatic experience he went through in the madrasa. He was allegedly raped by his teacher, Alauddin, the principal of the madrasa. According to Jahid's father, after molesting Jahid, Alauddin threatened him that if he told anyone about the rape, he and his family would die from vomiting blood. However, seeing Jahid's disastrous condition, one of Jahid's friends called his father and after much persuasion, Jahid described what had happened to him.

Alauddin was arrested by the police who later found that Jahid was only one of Alauddin's many victims. He confessed to the police that he had raped two other children in the same week he raped Jahid. Students of Panihata madrasa, most of whom are eight to 15, also revealed accounts of inhuman corporal punishment by their teachers. Lashing mercilessly with two or three sticks bundled together, shackling kids for a full day, slapping them on the face and frequent sexual molestation—these are the ways Alauddin and his colleagues used to treat their infant students who, according to Islam, are free from sin and cannot be held accountable for their wrongdoings.

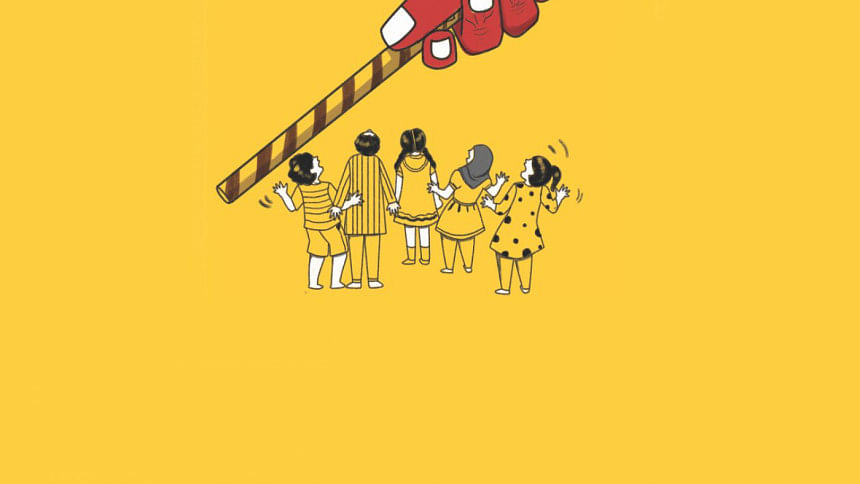

Recent reports published in the media about brutal punishment and sexual abuse in madrasas indicate that Jahid's fate in Panihata madrasa is probably not an isolated incident. Students of madrasas, many of whom are from poor families or even orphans, who have to spend their entire student life in the enclosed, residential premises of the madrasas, rarely get the chance to inform their guardians in case of any abusive treatment. Despite that, at least 42 cases of brutal punishment and sexual abuse in madrasas were reported in the media just in 2018. This indicates that these reports of molestation in madrasas is the tip of a much bigger problem. But why in madrasas, where children are supposed to live in a sacred environment, do they sometimes face the most traumatic experiences of their lives?

The answer may lie in the current administration system of the madrasas which lacks accountability and are extremely prone to political influence and corruption. There are various types of madrasas in Bangladesh which operate independently. They don't even follow the rules of the central and regional boards of Qwami madrasas. They provide non-formal Islamic education, run entirely on donation and do not follow any standard curriculum or academic process. Since there is no central administrative body to supervise these madrasas, their actual number cannot even be confirmed.

Nurani and Furqania madrasas provide elementary level Islamic education and Hafizia madrasas are residential madrasas where children are sent to complete Hifz course, a traditional method of memorising the entire holy Quran. Usually, the donor(s) who establish or support these madrasas also recruit teachers and such recruitments depend on their whims.

For instance, Alauddin of Panihata madrasa used to teach his students how to memorise the Quran. However, it was later found that Alauddin did not have any academic qualification. He never completed a Hifz course. According to Jahid's father, "He only had a skullcap, Punjabi and beard to prove his Islamic knowledge." He was recruited by a local leader of the ruling party who also happened to be the secretary of the madrasa managing committee. There is a madrasa education directorate, madrasa education board and Qwami madrasa education board (Befaqul Madarisil Arabia) in Bangladesh but none of these bodies could develop a mechanism to recruit qualified teachers for these institutions. As a result, education and upbringing of a huge number of children, mostly from the marginalised part of the society, depend on teachers and institutions whose educational standards are questionable and whose ethical standards are not clear.

Many of the Nurani and Furqania students get enrolled to higher level Qwami madrasas for further education where they enter into an even stricter environment. For the rest of their academic life up to Dawra-E-Hadith (Master's level degree), they learn mostly Islamic theology and Urdu, Arabic and Persian literature. In fact, they have to learn Urdu, Arabic and Persian languages to study the traditional Islamic books which are mostly written in these three languages. The teachers of these madrasas follow instructions only given by their respective regional boards and these boards are beyond the purview of any type of government monitoring. They have been rejecting all efforts of curriculum reformation supposedly to protect the "sanctity" of their traditional syllabus which has been producing a huge number of jobless youths. According to Political Economy of Madrasa Education in Bangladesh by Professor Dr Abul Barkat, every three of four Qwami madrasa students remain jobless after their graduation.

Many of these Qwami graduates ultimately have to rely on their teachers to get jobs in different mosques and madrasas which make them even reluctant to raise their voice against their teachers in case of abusive treatments.

The situation in Alia madrasas is in no better shape. There are more than 10,000 Alia madrasas in Bangladesh which are administered by the government's madrasa education board. Most of these madrasas, particularly the government ones, have become a hotbed of partisan politics like all other government colleges. When Nusrat, a student of Sonagazi Islamia Senior Fazil Madrasa (an Alia madrasa), was killed allegedly by the order of the principal of the madrasa for protesting against his sexual abuse, local Awami League leaders supported him and tried their best to protect the killers. In fact, reports revealed that he was hand-picked by the local ruling party leaders who hold key positions in the madrasa management committee despite his previous records of financial and sexual misconduct. In Bakerganj upazila of Barisal district, when a madrasa teacher protested against the illegal use of the madrasa's property by the ruling party leaders, he was abused by the ruling party workers who poured faeces on his head in broad daylight. Shortage of qualified teachers, lack of students in the science discipline, shortage of resources has crippled many of these madrasas whose students just attend the exams to keep their studentship.

Madrasas in Bengal have been producing righteous Islamic scholars from time immemorial. They have protected social values and even struggled against unjust rulers such as Fakir-Sanyasi rebellion in the 17th century. Due to lack of an accountable administrative system, these madrasas are being occupied by unqualified teachers and corrupt political leaders which can put into question the entire Islamic education system of the country in the future if this process goes unchecked. Islamic scholars should ponder upon the recent incidents and act quickly to ensure accountability, safety and quality education in the madrasas where more than three million students go to build their future.

Md Shahnawaz Khan Chandan can be contacted at [email protected]

Comments