THE MESSENGER

Photo courtesy: International Committee of the Red Cross

1971, for families torn apart or displaced by the war, was a time of profound uncertainty, of not knowing where or how their loved ones were, of waiting for news – any news – good or bad.

During those volatile times, a 17-year-old girl from Manikganj provided silent support to desperate families looking for information on their near and dear ones. Monowara Sarker helped trace missing family members, deliver messages and repatriate stranded Bangladeshis, as a tracing officer of the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC).

Like the thousands of displaced families she assisted during the course of her work, Monowara herself had escaped to Dhaka leaving behind her family in the village.

"When the war broke out, I had been studying to become a teacher. My father's business was failing and we were on the verge of starvation. I was the eldest of eight children – seven sisters and a brother – so I needed a job very badly," she recalls.

In September, defying the increasingly unstable political situation of the country, Monowara decided to sit for the primary teacher's training exam at the Primary Teachers Training Institute (PTI) in Manikganj. It was here, while she was taking the exams, that she was noticed by some Pakistani Army officers and offered a job.

"They realised that someone who came to give the test during these times must be desperate, and so they sent some local Al-Badrs to ask me if I wanted a job," she says. "I was terrified – obviously I wouldn't take any job they were offering, but how could I turn them down without risking my life?"

At the advice her family and neighbours, Monowara left home in a hurry for her aunt's place in Dhaka. But she still needed a job to support herself and her family, and applied for a position at the Red Cross, which was just setting up its offices in Dhaka.

"When they heard I had just escaped the Pakistanis, they asked me when I could join," says Monowara, who became the first local recuit of the ICRC. "I had no idea how to do the work of the ICRC, but I picked it up quickly along the way."

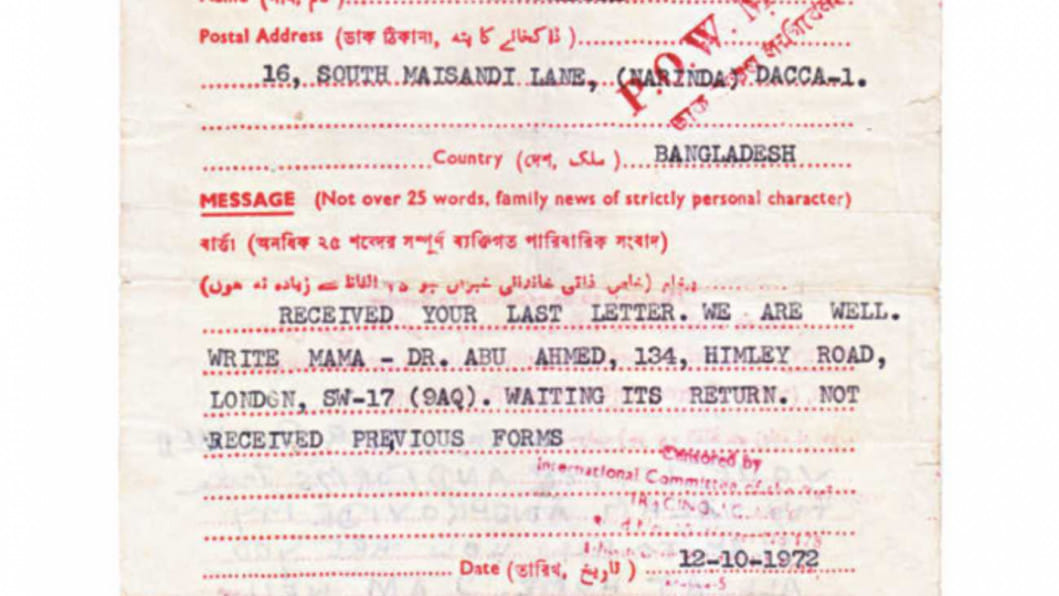

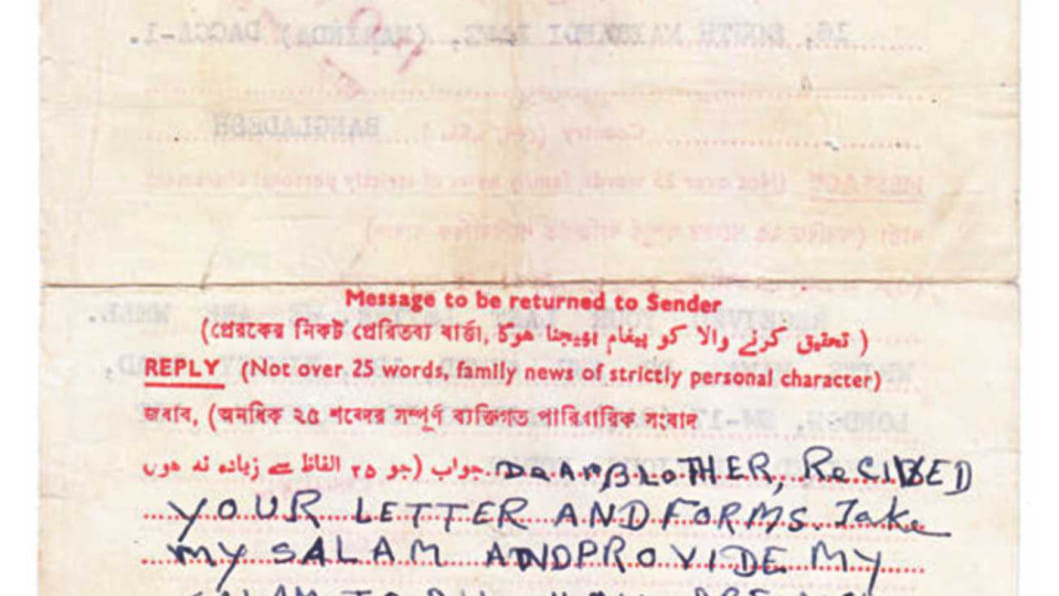

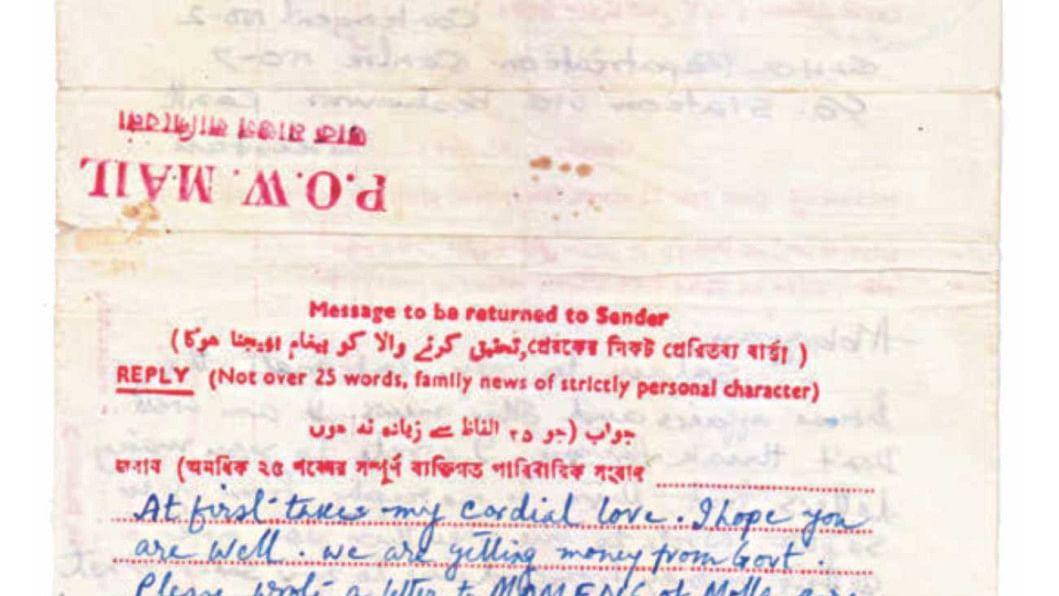

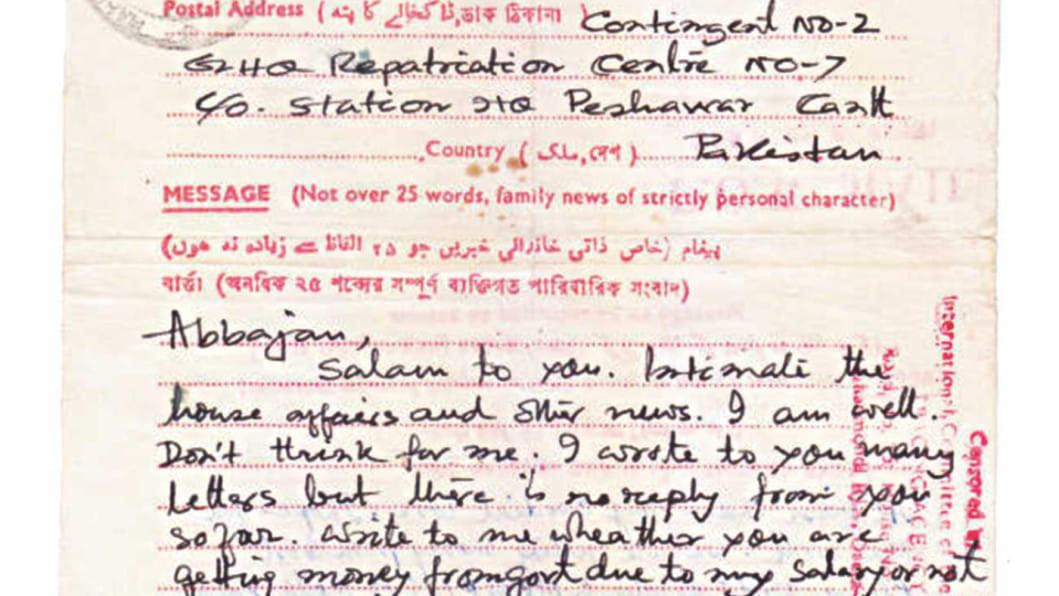

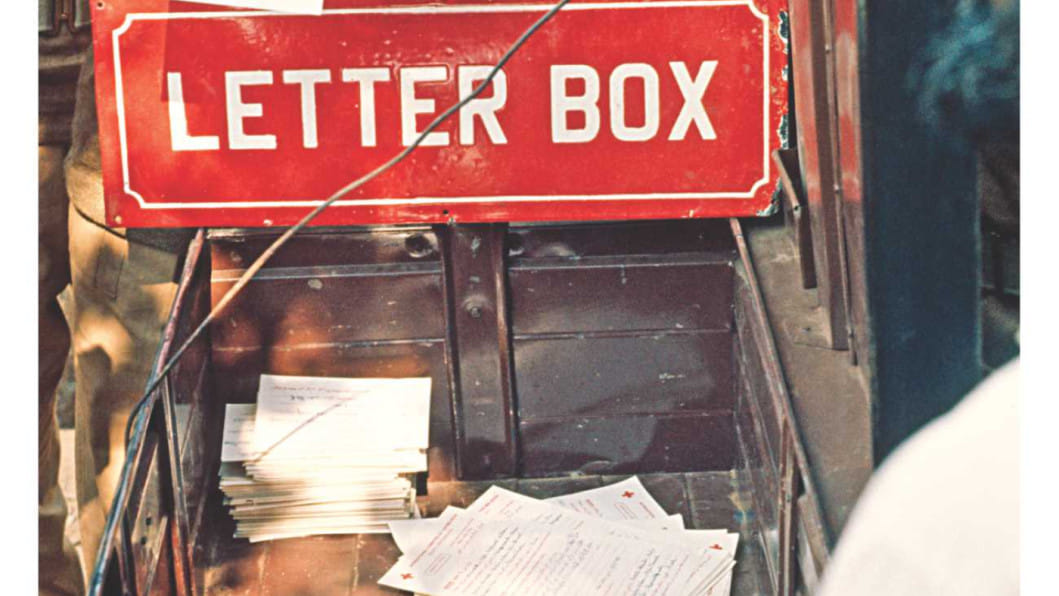

One of Monowara's tasks was to coordinate the ICRC message forms, used by people to communicate with their friends and families scattered across East and West Pakistan. Before the War, postal bags between erstwhile East Pakistan and the Western wing of the country were routed through Karachi. After December 3, 1971, this network collapsed completely and the ICRC's message forms became a reliable means of sending and receiving information.

"The first message form I used was to send a note to my parents telling them I was okay. I had no others means of communication with them," remembers Monowara. "That's when I realised what a simple yet powerful service the ICRC was providing."

The Red Cross Message Forms were handled free of charge by the respective postal services. Mail was collected at the post offices, repatriation camps and military bases in Pakistan. They were then sent to the ICRC Headquarters in Switzerland. From Geneva, they were transferred to the Tracing Agency located in Bangladesh. Mail from Bangladesh was delivered to destinations in Pakistan following a similar outward route.

Only messages not exceeding 25 words were allowed. Both Military and Civilian correspondence were censored at Tracing Agencies and words not related to family matters written in Bengali or English were defaced with indelible ink.

"We were in a unique and difficult position. As a humanitarian agency, we had to remain 'neutral' or at least seem neutral, in order for both Pakistan and soon-to-be Bangladesh to accept us," argues Monowara. "We had the mandate only of sending messages about welfare from one family member to another. We had to be careful to blacken out any word which contained a political message or could be interpreted as 'anti-state'."

"We didn't have a choice but to do so, to ensure we could continue to operate here," she adds.

In addition to forwarding messages, ICRC conducted the difficult task of tracing people who had gone missing during the war. "We had to track three kinds of 'missing' people – Bengalis displaced by the war, Bengalis picked up or abducted by the army and Bengalis and Pakistanis who were stranded in West Pakistan and Bangladesh respectively," she informs. "At first, I used to think – how is it possible for foreigners to locate the missing people? Is it really true?"

Gradually, Monowara learnt how to do the challenging task of tracing herself, conducting interviews with witnesses, visiting the last known address of the missing and investigating the circumstances under which the victim disappeared.

"One of the hardest things we had to do was look for people who had been abducted. We got so many cases that we simply could not resolve, including the case of Zahir Raihan," she shares. "Our foreign delegates dealt with the most sensitive cases. They would go from one army personnel to another, asking for information. As per the Geneva Convention, the Pakistanis were required to help us, but very often they did not."

According to Monowara, the ICRC could solve as many as 40 percent of the cases involving abducted persons. "Many people had escaped somehow and made it across the border, or were hiding in another district. We were able to trace many of them and give the good news to their families," she adds.

The process of collecting sensitive information, out in the field by herself, involved being exposed to various risks. Monowara recalls her first case in which she was required to visit Mohammadpur, where the majority of Urdu-speaking people lived. "I was so scared. There I was, a young Bangali girl, in the midst of war, trying to gather information about a woman of Pakistani origin."

Thankfully, no one asked her any questions, and she was able to connect an old and ailing 100-year-old woman, living with her 80-year-old daughter, to their kin in West Pakistan.

In total, the ICRC solved as many as 180,000 tracing requests and delivered 2.8 million messages.

The War of 1971 had left about 120,000 Bengalis stranded in Pakistan, mainly military personnel and civil servants from the former East Pakistan and their families; thousands of Pakistani civilian internees remained in Bangladesh, and prisoners of war in Indian camps. On August 28, 1973 the governments of Bangladesh, India and Pakistan concluded a tripartite agreement in New Delhi arranging for the repatriation of Bengalis in Pakistan, and Pakistanis interned in Bangladesh. The ICRC went on to facilitate the return of around 120,000 Bangladeshis from Pakistan to Bangladesh, and 198,000 from Bangladesh to Pakistan.

"Many Bangladeshis who worked there were stranded in Pakistan after the war. Their families were in Bangladesh. But how would they come? They didn't have a visa or a passport. ICRC used to issue a one-way travel document to ensure their safe return," she informs.

The bilateral relations between Pakistan and Bangladesh were established on February 22, 1974. Following the establishment of embassies in the two countries, the ICRC decided to fold their operations in Bangladesh in 1975. They transferred the pending cases and all the paperwork to the Bangladesh Red Crescent Society.

Since Monowara was the first local recruit of the ICRC, she was asked to assist in the process of transition for six months. After that, she was offered a full-time job with the Red Crescent Society, where she went on to spend her entire career. She retired as the Director of Restoring Family Links Department of the organisation. Monowara was awarded the Henry Dunant Medal, the highest distinction of the International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement, for her lifelong commitment to reuniting families.

What Monowara did, as a 17-year-old, defied the societal expectations of a young Bangali girl. She inserted herself in dangerous situations without a care about her safety for the sake of tracing missing persons and reconnecting families. Families had the right to know, says Monowara, about what happened to their loved one. Were they alive? Detained? Displaced? Refugees? "Even if a family member had passed away, the family needed to know – needed to grieve, needed the closure," she concludes. "That's the least we could do."

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments