Let the rivers run wild

To this day, there is that one Bangla poem that I cannot but help start reciting in my head if I find anyone saying the words Choto Nodi. The poem, you have probably guessed by now is, Amader choto nodi chole baake baake and goes on to describe a river in Bangladesh. There is possibly no better image to represent Bangladesh either, if it is not that of a river.

Yet, over the years Bangladesh has seen a shrinking of its rivers, and a rapid and gross overtaking of riverbeds and its adjacent areas for the sake of development.

And this rampant development has managed to put on the line not only us humans but also the many hundreds of species that rely on these habitats adjacent to the rivers.

“The Bengali civilisation has grown surrounding the river-banks. This is a relationship that goes back many hundreds of years,” says Bangladesh Poribesh Andolon (BAPA)'s Joint Secretary General Iqbal Habib.

Despite this reliance on rivers, over the course of a few decades, we have managed to completely degrade and even kill our rivers. At this point, it seems protecting the rivers and nearby areas with a strict regulatory measure may be the only answer to change the course of tide in favour of healthy rivers.

“Currently there is a provision to protect 50 meters inwards of a foreshore of any river bank. Which is something I can definitely get behind. This provision, under the Bangladesh Inland Water Transport Authority (BIWTA), means when someone wants to take on a development project in or around the river area they can apply to the concerned authorities for permission. And the authorities can then judge whether that area needs to be protected for biodiversity or not. In that way, the conservation efforts will not exclude all development projects entirely,” opines Habib.

The chars and grasslands of some of our major rivers—Padma, Brahmaputra and Gorai—may appear empty to the naked eye but these areas serve as key habitats for a range of wildlife, from birds to reptiles, many of our grasslands are ecological hotspots.

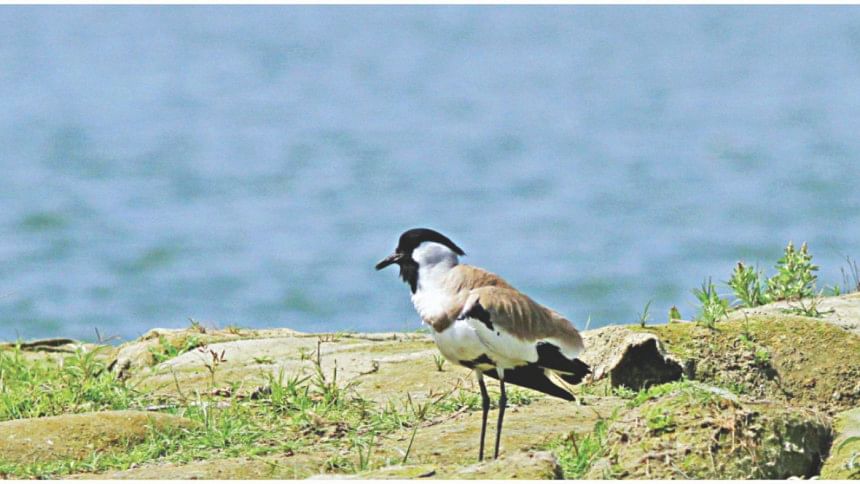

A recently published paper on a near-threatened and rarely documented bird—the River Lapwing on the chars of Padma and Gorai rivers—is yet another example of how the aggressive impact of development is putting biodiversity that relies on the rivers at risk.

“In recent decades, dredging operations have been carried out to facilitate navigation and flow of water in the Gorai river and these interventions may have disturbed the wildlife that relies on these habitats,” according to the research paper Surveys of River Lapwings Vanellus duvaucelii in Bangladesh and observations on their nesting ecology.

“It is likely this has also affected the breeding habitats of the River Lapwings and other species which nest on the sand beds of these chars,” says Sakib Ahmed, one of the authors of the research papers.

Rivers and surrounding habitats face other threats too—sand lifting, excessive pressure of fishing, increased sedimentation owing to 'river training' projects and so on.

The increased pressure on many parts of the Padma and Gorai rivers may mean that these areas will become unsuitable for River Lapwings and other riverine species in the near future. But that is not just it; when the birds leave a place, it is indicative of a larger problem. Birds are environmental indicators and their absence is a sign that the environment is in peril.

“It is not just one particular species that is at threat here. It is all those who depend on these riverways and adjacent areas who will be affected if conservation measures are not adopted,” says Ahmed.

The conservationists want these rivers, chars and adjacent areas to be brought under a legal framework so that these cannot be exploited any further.

They believe that a conservation effort targeted towards protecting the habitat will have a two-pronged impact- save biodiversity and the livelihood of locals.

RIVERS IN PERIL

It is evident even to the naked eye how much the Gorai river has changed over the years. This is in Kushtia. There are people here who remember the days before and after the Farakka Barrage completion in 1975, the days before and after Liberation War of Bangladesh and some even remember the partition. So, it is safe to say that these people are living annals of history. And they have seen the rivers change. The dam managed to change the dynamics of the river. It decreased dry season flow which has led to increased sedimentation.

In Bangladesh, several species, including the River Lapwing, the endangered Black-bellied Tern, Pied Avocets, Woollyneck Stork and Indian Skimmer and many other species will be affected because of increased human intervention, activities surrounding the rivers and its adjacent areas.

Researchers have also noted a large number of livestock—cattle—being transported through the sandbars of Chapainawabganj during a certain time of the year. This is the very place where these birds’ nest and forage. The scene imitates a movie scene, as hundreds of thousands of cows converge upon the sandbars, raising up a sand storm, engulfing the landscape in dust and the sound of hooves.

Conservationists wince, as realisation dawns that many nests and chicks have been trampled in this mad race.

For now, Bangladesh Bird Club has sent a proposal to the Bangladesh Forest Department to declare some of these sandbars in Chapainawabganj and Rajshahi as protected areas.

“We have plans to start our own surveys to monitor and eventually come up with conservation actions centering the areas in and around some of the major rivers. But that is not likely to start before next year,” says Jahidul Kabir, Conservator of Forests, Wildlife and Nature Conservation Circle of the Bangladesh Forest Department.

Protecting the rivers as areas of ecological importance is something that Jahidul Kabir agrees on as well.

He added that they are aware of the Bangladesh Bird Club’s proposal and work is going on centering the proposal.

However, what impact this legal framework can have is debatable, to the say the least.

Rivers are protected by our constitution. The Article 18(A) of the Constitution states: “The State shall endeavour to protect and improve the environment and to preserve and safeguard the natural resources, bio-diversity, wetlands, forests and wild life for the present and future citizens.” The State has enacted a number of laws including Bangladesh Water Act 2013, National River Protection Commission Act, 2013, and The Environment Conservation Act, 1995 (upgraded in 2010) which have provisions for the protection of the environment, and control and mitigation of environmental pollution.

But to this day, the rivers of Bangladesh continue to be dealt with blow after blow.

Which is why it makes sense to declare the entirety of the landscape around the rivers and the rivers itself which have been identified as biodiversity hotspots and areas of ecological importance as protected areas instead of targeting any one particular species for protection.

That way we can protect the rivers, the wildlife and the people who make their living off these waterways.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments