Technology at Tanguar Haor

It took three separate modes of transportation, a major fight between a bus driver and his helper, and a sleepless night before I managed to reach the foothills of Meghalaya to witness conservation and technology merge and in turn, make history for Bangladesh.

At the foothills of Meghalaya is the vast network of waterbodies that make up Tanguar Haor, where a team of wildlife conservationists and scientists of the International Union for Conservation of Nature (Bangladesh) and Linnaeus University in Sweden, set up camp for two weeks to try and understand flight behaviour, disease ecology and migration of wild ducks from Bangladesh to Europe and its connection with the spread of the highly pathogenic avian influenza through wild waterfowl from Asia to Europe.

Tanguar Haor is a unique ecosystem, where the wild and domestic co-exist—for better or for worse.

An episode of Man meets Machine meets Wild in Tanguar?

Watching the project unfold in front of me day in and day out was like watching the shoot of a National Geographic show with live commentary, performed by yours truly.

A typical day unfolded like this: I would wake up at 7:00am to find one group of scientists already returning on small country boats from their morning round of checking the mist-nets (nets put up inside the haor to safely get wild ducks for setting up solar GPS tags on them). If it was a good day, the wildlife conservationists would be returning with at least two to three wild ducks of certain targeted species and other species of birds to either ring them or fit them with solar-battery powered, GPS-enabled satellite tags.

Then would begin the next round of work for the morning. They would set up a small table under the Hijal trees on a mound that separated us from the water of the haor. Under the shade of the Hijal, the researchers would bring out their delicate science equipment—the solar powered GPS-enabled satellite tags, vernier calipers, small metal rings, weighing machines and a bunch of other equipment.

I am not going to go into excruciating details here but it typically took ten to fifteen minutes to fit a wild duck—which was either a Eurasian Wigeon, Common Teal, Northern Pintail or Garganey—with a satellite tag. The device is ten percent of the bird's body weight and designed in such a way that the bird would not have any difficulty flying.

“It is like when you wear glasses or a watch, you forget the weight is there, you learn how to not let it distract you. It is the same case with the satellite tags. They are designed in such a way that the bird does not feel uncomfortable with the weight of the tag,” Jonas Waldenström, a professor of Linnaeus University, who is also closely collaborating with IUCN in the programme 'Avian Influenza in Bangladesh: the role of wild waterfowl in disease transmission.'

The birds fitted with the solar tags are then released into the wild. On a side note, I cannot help but gush over what a wonderful sight it is—to watch the bird fly away into the azure blue sky, the mountains in the backdrop of the green and blue water.

The use of such telemetry has completely changed the understanding of how birds are studied.

A strange marriage of technology and nature and how it will benefit us

The first case of avian Influenza, or bird flu as we know it, was reported around 20 years back in Hong Kong. It occurred in poultry and has a hundred percent mortality rate.

Now comes the tricky part: a less harmful strain of the avian influenza actually occurs in wild ducks and, over the years, has developed many strains. The one that we know of as bird flu is the H5N1 strain of the virus, which when it occurs in poultry spells disaster.

But see, cases of bird flu occurred in Europe as well over these years. Now, somehow, the flu managed to travel all the way from Hong Kong to the European mainland.

The thing is, no wild ducks which migrate from the South Asian countries actually fly all the way to Europe. But these very ducks are likely meet birds from Europe somewhere around Russia, from where the virus spreads.

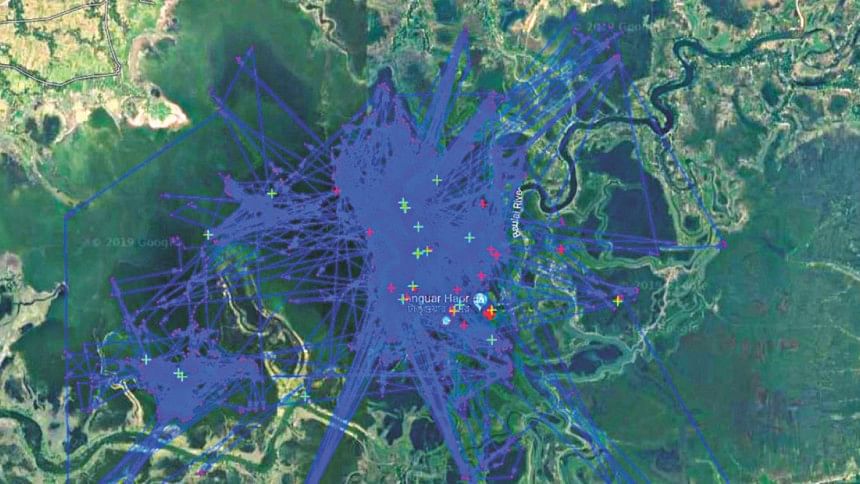

That is one of the things that we are trying to find out, say the scientists on the field but these birds and their satellite tags, are amazing repositories of data. The tags will relay back such information as wind speed, direction, location, habitat preference. And in this age of big data science, this wealth of information can be used in so many ways.

While one objective of the project is to understand migration patterns and the global spread of avian influenza through wild waterfowl, the other objective is catered to a more localised perspective.

“We are also trying to understand what waterbodies in Tanguar Haor are actually used by these waterfowls. This will also give us information on what other haors or areas in the country are used by wild ducks apart from the ones we already know of,” says Raquibul Amin, country representative of IUCN.

This will help us understand what other areas in the country need to be brought under a management plan for conservation, he opines.

Experts also believe this programme will act as an early warning sign for Bangladeshi livestock farmers and the government. “When a bird is tagged in Bangladesh, we already know that this is part of its migration route. Now, when a satellite tagged duck from Bangladesh travels to any place with a reported avian influenza outbreak, we will immediately be alerted and we can take measures,” says Amin.

This is important because avian influenza in a wild waterfowl may not have any economic impacts but when transmitted from wild to domestic, it will result in huge economic losses.

“In this Tanguar Haor landscape, this has important implications. Look around—every day, thousands of domestic ducks go out to feed in close proximity with wild ducks. The chances of disease transfer are very high. And once in domestic poultry, the possibility of it exploding to a pandemic is massive and these poor farmers will have to count huge losses,” says ABM Sarowar Alam, principal investigator of IUCN for the programme.

Final days in Tanguar Haor

As the days in Tanguar Haor, slowly started coming to a close, more questions popped up in my mind over the strange realities around us. Can conservation science actually benefit from modern technology? Wasn't modern technology the very reason wildlife was threatened?

It also throws light on the fact that science and even conservation science is actually very anthropocentric. Humans need to save wildlife, because study after study has shown, that all components of the natural ecosystem have certain values and benefits us in certain ways.

And now scientists are using the aide of technology to come up with possible conservation measures.

As we packed our bags on the last morning at Tanguar Haor and got on the boat for our journey back to Tahirpur in Sunamganj, I saw the scientists huddle together on their cellphones to watch the flight of their satellite tagged birds. I heard them squeal in childish delight “The pintail is such a restless one. Look at it just whiz all over the Haor.”

Maybe science for the sake of science will eventually provide important solutions and answers for humanity and the broader environment as well.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments