What happens to our e-waste?

What do you do with the damaged battery or chargers of your cell phone? Where do you keep your fused bulbs and abandoned switches? What about obsolete computer accessories?

After stashing them in the corner of the house for a long time, these entirely discarded yet less expensive household and office appliances are usually destined for the dustbin alongside solid waste. On the other hand, comparatively expensive obsolete products, e.g. freezers, laptops, computers, electric fans, or ACs, are taken to the shops for repair. If they are considered irrecoverable, however, people are more likely to sell them to save up for a new one.

“After buying damaged computers or laptops, we first separate the parts that can be re-used—be it a hard disk, monitor, CD-ROM, keyboard, or battery. However, we usually sell the parts like damaged wires, casings, plastics, headphones, or other accessories to the hawkers or brokers,” says Foyez Ahmed, Sales Executive at Dreamland Computer in BCS Computer City, popularly known as IDB Bhaban. “The parts that remain unsold for a long time, are simply thrown out,” he adds.

The fact is that Bangladesh has been introducing more and more electrical and electronic products over the years, but in proportion to that, we have had no significant institutional preparedness or strict policies for disposing of the ever-growing volume of waste, popularly known as e-waste. As such, e-waste ends up in landfills with solid waste. Improper disposal means that heavy metals in e-waste like lead, chromium, cadmium, mercury and so on, end up in the soil, water and air, and eventually in our bodies through the food we eat.

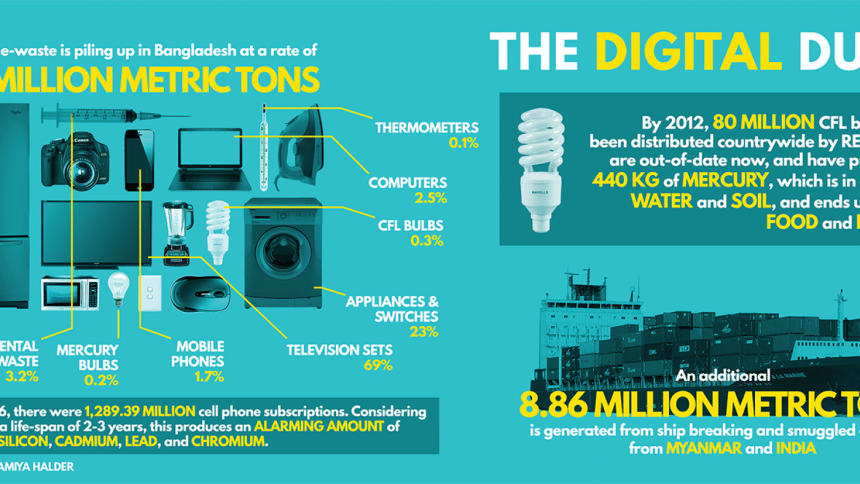

It is sad but true that there are no specific facts and figures by the government on how much e-waste is generated in the country every year. But if we look back, over eight crore Compact Fluorescent Light (CFL) bulbs were distributed countrywide by the Rural Electrification Board by 2012. These are out-of-date now. Assuming that each CFL bulb contains an average of 5.5 mg of mercury, eight crore of these have produced 0.44 metric tons of mercury, which has spread into the environment. On the other hand, according to statistics by BTRC, the total number of cell phone subscriptions reached 128.939 million by the end of July 2016. If we assume these phones have a lifespan of two–three years, these phones generate an alarming amount of e-waste in the form of mercury, silicon, cadmium, lead, chromium and more.

However, according to a 2016 study by Environment and Social Development Organisation (ESDO), every year Bangladesh generates roughly 1.24 million metric tons of e-waste from televisions, computers, mobile phones, CFL bulbs, mercury bulbs, thermometers, medical and dental waste, household electrical appliances and switches. In addition, 8.86 million metric tons of e-waste is generated through ship breaking and smuggling from India and Myanmar.

Since recycling e-waste is a lucrative business, hawkers and brokers usually sell it to different small businessmen of old Dhaka based on the category of waste. “Circuit boards, plugs or other accessories are sold to Nimtoli for further use, while the dismantled brass, copper or iron is sold to Becharam Deuri or Dholai Khal for producing scrap metal for automobile factories. Plastics and damaged wires are sold off to the plastic businessmen of Islambag, in order to make toys for children or household products,” says 35-year-old Mohammad Shipon, a plastic recycling businessman in old Dhaka's Islambag. “Sometimes, the damaged bulbs, batteries, chargers, plugs, etc. that are collected by waste-pickers are randomly sold off to businessmen who re-use the components and manufacture moulds,” he adds.

Unfortunately, most of the time e-waste is handled by child workers. According to a 2014 study by ESDO, every year over 15 percent of child workers die in the process of recycling e-waste and its after-effects. More than 83 percent of them are exposed to toxic substances, become sick and live with long-term illnesses.

When visited at Nimtoli, 12-year-old Mohammad Saju was dismantling electric fans, 15-year-old Nahid was busy removing circuit boards from cell phones, while 10-year-old Robiul was separating wires from a mound of different types of e-waste.

“I have been dismantling the plastics from obsolete electric fans for the past five years. Since this is the only source of income to support my family, I am bound to do this. I have never felt that it is harmful for my health,” says Saju. Like him, most of the shops have child workers who work in a completely unprotected environment, without knowing of the deadly health hazards.

Dr. Rashid-e-Mahbub, Chairman of National Health Rights Movement, informs that though e-waste does not create any immediate health hazards, those who are directly handle them for an extended period of time are at a high risk of developing different health complications. “They are exposed to lead and inhale mercury on a regular basis. This is extremely harmful for the lungs and can have long-term negative health effects,” says Mahbub.

However, though environmentalists and private organisations working to protect the environment are continuously pressuring the government to undertake immediate steps, there is hardly any institutional preparedness from the side of the government. Since the ICT Division aims to introduce effective use of modern technologies in important sectors, Mohammad Atiqul Islam, Deputy Director (Planning), Bangladesh Hi-Tech Park Authority informs that they are working with Re-Tem Corporation, a Japanese e-waste management company, to build an e-waste dumping plant in Bangladesh.

“They have already worked on building primary awareness on the current e-waste situation in Bangladesh, in association with Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) and New Energy and Industrial Technology Development (NEDO). We have provided them five acres of land at the Kaliakoir Hi-Tech Park for the plant,” says Islam.

On the other hand, Quazi Sarwar Imtiaz Hashmi, Additional Director, Department of Environment (DoE) informs that they have been working on creating a separate legal framework for the e-waste management from 2012. “We have put up the draft guideline online for feedback from the public. Afterwards, it will be sent to the law ministry for further processing,” says Hashmi. Though the timeframe for obtaining public feedback ended last April, Hashmi could not provide detailed information on the present state of the guideline—whether it has been sent to the Law Ministry or not.

Hashmi also says DoE is not the appropriate authority to deal with e-waste management, since the city corporations are responsible for managing all sorts of wastes. But as a regulatory body, DoE assists the city corporations and is working on the dumping plant.

Since most of the e-waste is handled and dumped in old Dhaka, Khan Mohammad Bilal, Chief Executive Officer of Dhaka South City Corporation (DSCC) was asked about their disposal. Bilal answers he knows nothing about the Japanese company, and that DSCC is currently busy dealing with the solid wastes of fruits. “We have kept it (e-waste) in consideration and have started to discuss doing something feasible,” says Bilal.

The government's 'delayed response' to e-waste management and the nonchalance of consumers when disposing of appliances can produce considerable damage to our environment in the decades to come. Therefore, there is no alternative but to make a change today, before it is no longer within our capacity to manage.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments