The global showcase of films

The last trimester of the calendar year is possibly the most exciting time for film lovers—prestige release season! The season opens with Toronto International Film Festival (TIFF), which has premiered and showcased contenders such as La La Land, The Imitation Game, and Room. Especially of interest is its People's Choice Award section which has gone on to discover Best Picture winners such as American Beauty in 1999, Slumdog Millionaire in 2008, and Moonlight in 2016.

This year too, the festival anticipated films that may catch Oscar buzz such as Bradley Cooper's directorial debut A Star is Born and Damien Chazelle's Ryan Gosling-starrer biopic First Man. But the People's Choice Award went to Peter Farelly's Green Book—a fictional retelling of the racism faced by an African-American jazz musician, played by Mahershala Ali, touring the American South with his Italian-American bouncer, played by Viggo Mortensen. The first runner up (and personally what I had thought would win) was Moonlight director Barry Jenkin's second film, If Beale Street Could Talk, based on James Baldwin's novel of the same name.

However, apart from the prestige releases, TIFF is also a platform for experiencing an array of exceptional films that display new cinematic feats—regularly overshadowed by big-budget Academy favourites. So, here's a roundup of other films screened at TIFF that may not make it to the awards but should definitely make it to your watch-list:

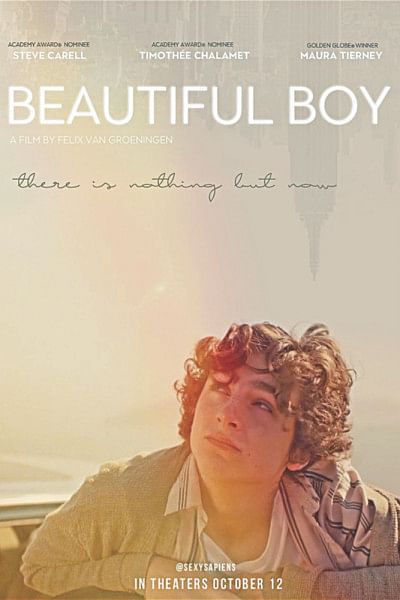

Beautiful Boy

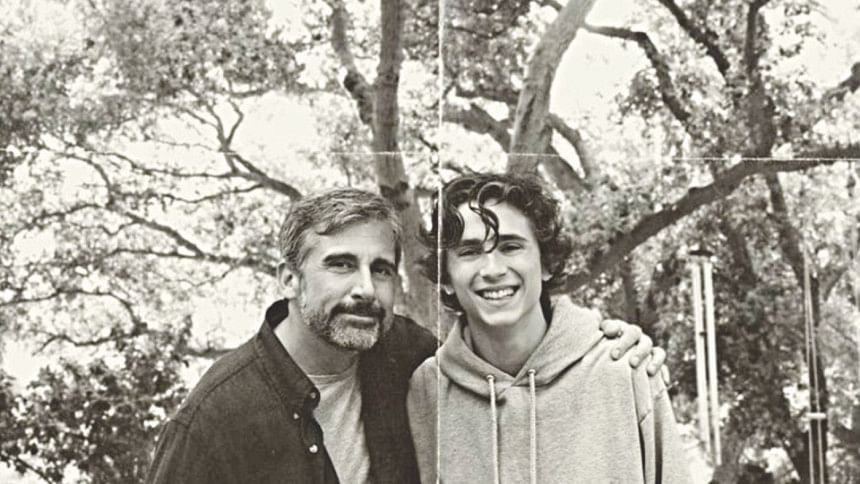

Timothée Chalamet stars as a tormented teenager whose meth-addiction spirals his middle-class family into an abyss of sorrow, rage, guilt, regret, and hope. Steve Carell plays a confused father who is devastated when he learns about his son's problem and is willing to go to any length to get him back to as he remembers him—a sweet, loving, innocent young boy. The film follows father and son's journey as they battle the circular, often disheartening, patterns of recovery and relapse.

Based on a memoir, Belgian director Felix van Groeningen's English language debut crafts the paradox of helplessness and expectations of parenthood on-screen with a moving soundtrack by the Icelandic post-rock band Sigur Ros. Mature and complex performances by Chalamet and Carell strike the perfect overtone of a father-son relationship. Both actors build on their reputation of Oscar-nominated performances and brighten the screen with the softness and struggle of family bonds. Despite addiction being a central story arc, the film's strength lies in the delicateness and restraint with which the story depicts men, both father and son, during this vulnerable and tumultuous phase of their lives.

Manto

Nandita Das' biopic of the progressive writer Saadat Hasan Manto is a critical and emotional look at Partition through the writer's stories and essays. Played by Nawazuddin Siddique, Manto is committed to speaking the truth and only the truth. The story begins in Bombay, with glimpses of early Bollywood, where Manto used to write scripts, and follows the protagonist through post-Partition communal violence, migration, obscenity trials, and consequently, alcoholism.

Even though the biopic lacks the realism and provocativeness of Manto's writing, Das seamlessly incorporates his most-famous stories and essays with a surrealism that is equally stirring and curious. Literary feats such as “Thanda Ghosht”, “Khol Do”, and the famous open letter to Nehru, are weaved wonderfully into the majorly linear storytelling.

What is obvious about the biopic is that it imagines Manto's writing and his life's story keeping the contemporary in mind—while it talks about the past, it speaks to the present ethno-religious nationalism on the rise all over South Asia. Using flat colours of grey and brown, Das employs a traditional

Das employs a traditional nostalgia of an era that longed for unity, all the while stripping people of their homes and identities. The timeless ideals of the film's content make Manto extremely relevant for today's audience.

Las Ninas Bien (The Good Girls)

This Mexican film explores the lives of ultra-rich housewives during the country's economic crisis of 1982. Directed by Alejandra Marquez Abella, the film provides a close-up look of the wealthy and fashionable, and the emptiness that comes with being on top of the hierarchy. With an aesthetic finesse of new heights, Abella folds the toxic and vile nature of rich socialites within its disguise of makeup, high-heels, and Gucci-Versace.

Rarely is a national monetary crisis explored through the eyes of the women who are affected by it. Within the narrative, we see how these women are often side-lined or ignored by their macho husbands who are equally incapable of improving the situation. And then there is the psychological turmoil a financial crisis can bring to women who never learnt to value life beyond what is simply materialistic. The film is special in its genre because while it depicts the upper class in its entirety, it consciously avoids its glorification and treats its subjects with scepticism and suspicion.

Abella executes the film with the sensitivity it needs to understand women trapped in a world of vanity controlled by men—and how that does not excuse women for their complicity. The film employs a dark irony to protagonist Sofia who we never manage to sympathise with, due to her sheer arrogance and pride. Fantastically played by actor Isle Salas, who speaks through strong glances, pursed lips, and commanding hands, the protagonist is an extension of Marie Antoinette who infamously said “Let them eat cake” during the French Revolution, when she heard peasants were starving from not being able to afford bread. Enveloped in an aesthetic masterclass of composition, framing, and colour, The Good Girls provides a deep and dark prophecy for the unapologetically wealthy.

Shadow

Chinese director Zhang Yimou of Raise the Red Lantern fame comes through again in this action-packed historical-drama. The story is an old one—two nations at war with claims to the same land. Yet, the narrative is one with a twist that is poetic as much as it is thrilling. But what makes this film a true delight is its visual magnificence—the scenes look as if the landscape is painted on soft silk. It is a cinematic masterpiece, with monochrome colour-grading, calligraphy, and use of traditional Chinese ink-wash painting to design the mood of its audience.

To top it all off, the film demonstrates neatly curated, detailed, and technologically augmented action sequences that explore and experiment with the genre of historical warfare itself. While set in the past, the weapons used in the films are hyper-real and futuristic adding an exciting layer of fantasy.

Although, I must acknowledge that the film falls into the trap of one-dimensional female characters with motivations based in patriarchal customs of ancient China. Many may say that this was done to maintain historical accuracy but considering the futuristic artillery used in the film, it feels as though it was really a crime not to write stronger female roles for a story which is otherwise fantastic. While it fails to give women agency, it does explore the psychological quarters of dark and twisted men, making it a remarkable thriller that shines for its technical and visual feats.

One Last Deal

One Last Deal by Finnish director Klaus Härö is about an ageing local art dealer Olavi, who is struggling to keep up with the tide of time—no one buys traditional art anymore and the rent in Helsinki is increasing due to urbanisation. At this moment of financial and existential crisis, Olavi is visited by his estranged grandson, Otto, looking for an apprenticeship. At first reluctant, Olavi hires his grandson upon discovering the boy's knack for salesmanship. As they crack open one last shot at salvaging the business, complications of absent parenthood, corporate jealousy, and the darkness of old age surround the story's muted narrative.

The drama which is set in the backdrop of minimal, Scandinavian landscape, hits a familiar chord of estrangement ever so common in urbanised spaces where nuclear families are increasingly becoming alienated. The relatable, sometimes cliched cost of individualism proves a compelling arc in this highly emotional tear-jerker. Every single audience in the theatre was sobbing by the end of this beautiful story. One of my favourite films this season, One Last Deal, engulfs the audience with a longing for warmth and a realisation of loss.

Sarah Nafisa Shahid studied Art-History at McGill University, Canada. Follow her on Twitter @I_Own_The_Sky for more art and film commentary.

Comments