Bhitargarh: destroyed before discovery

There was a king named Prithu Raja in northern Bangladesh in the 13th century. He had a fort city in Panchagarh called Bhitargarh, and he may or may not have died by committing suicide in a lake. This is the extent of what we know about this ancient fort city and its king. The rest hides beneath the rolling green fields and tea gardens of Amarpara union.

Ask around and people will say that the main attraction of Amarpara union in Panchagarh is a vast lake, locally called Moharajar Dighi, which stretches up until the border with India. You can come to this place to bask in the gusts of wind coming in from the lake and munch on the piping hot piyaju being offered by hawkers. Then you can choose to climb up either of the oddly shaped hillocks flanking the ghat of the lake—the mounds even have short staircases built into them for easy access. I chose the one on the right.

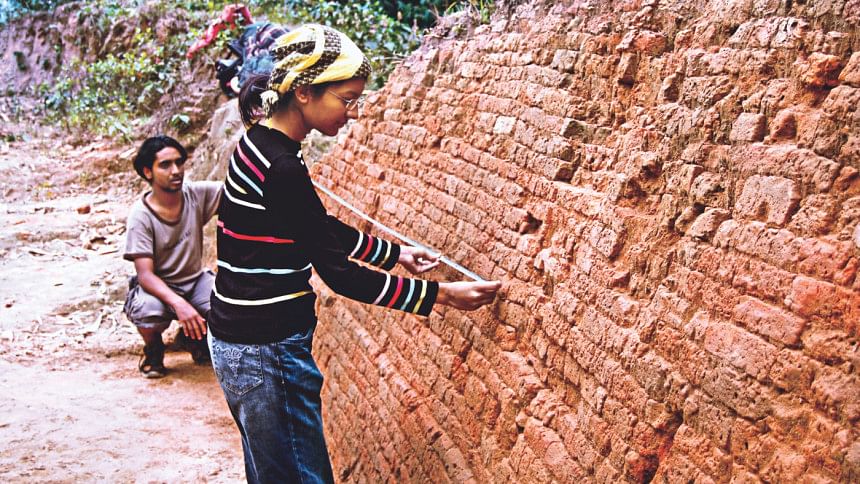

The first thing you notice is that the mound is not exactly the hillock it poses to be. It seems to stretch on for yards and yards…almost like a wall. There are bricks jutting out from the beneath the roots of the trees, and the bricks are narrow and red and not layered in with cement. They do not look like they are from this time. Because they are not. In fact, cement would not be invented for another 1,500 years from the time that archaeological experts believe this structure to have been built.

You may not know—many of the tourists visiting this place don't—but you are standing on top of a dam belonging to the ancient city. The centuries have not been kind. Layers of earth cover the dam and large trees have taken root from atop, and even the stairs that you just used to climb have been constructed by slicing into the dam. But it's all there, waiting to be unearthed and revived.

"Bhitargarh is the largest fortified settlement in South Asia, extending over an area of about 25 square kilometres enclosed within four concentric quadrangles surrounded by ramparts and moats," informed Dr Shahnaj Husne Jahan, an archaeologist and professor at University of Liberal Arts, Bangladesh who has been researching the site since 2008. The whole union is littered with subterranean temples and monuments, she found.

However, 10 years on, the government has taken no initiative to unearth and preserve this city. Meanwhile, the situation is further complicated by the fact that almost all of this lies buried under private property.

For example, last week an 11-year-old boy led me to his grandfather's plot of land to show me the ruins of a structure. They have planted tea saplings across the plot, in hopes of turning it into a tea garden.

"There, do you see it?" he asked.

"See what?" I replied.

He pointed to a patch on the ground where the rocks were more reddish and polygonal, and suddenly it seemed impossible that I had missed this. It was clearly the top of some archaeological remain, trying to burst its way through the earth's crust.

Similarly, another pyramid shaped temple upheld by rows of broad columns lies under the home of an old woman named Ashima. The locals call the site Rajar bhita.

"The pillars start right from here," Ashima, a sexagenarian matriarch who goes by one name, pointed out, "and goes on all the way under those homes." Small piles of medieval (or maybe even pre-medieval) bricks lay around Ashima's house, and her chickens have pecked away at holes in the bricks for tasty bugs.

Ashima's home consists of three houses gathered around a courtyard, with a sizeable betel nut garden in the backyard. The pyramid-shaped temple lies beneath all of this, Dr Jahan and her team have found.

And herein is the problem—if this temple has to be unearthed and displayed before the public, Ashima's entire household has to be moved. Ashima, however, states that she would consider giving up her ancestral land if the government approached her with compensation and land somewhere else.

"But nobody from the government has ever approached me with anything," she said. Three years ago, in 2016, the then director-general of the Department of Archaeology, Altaf Hossain, had told this newspaper that they were trying to acquire the land from the locals with the help of the ministry. Seems as if the owner of the land holding one of the most important archaeological monuments within Bhitargarh is yet to be contacted regarding this. Almost all the locals this correspondent spoke to said the same thing—nobody from the department of archaeology has visited them in a long time.

Meanwhile, even though the sites at Bhitargarh are protected by a direct order from the High Court, destruction continues. "The locals own the land, and use it as they see fit, without being conscious of protecting the heritage," stated Dr Jahan. She has been documenting the sites for a decade now, and has volumes of photographs archiving the destruction. She flipped through them one by one. "Here, you can see the school. The boundary wall of Bhitargarh runs past the school. And here you can see that they built a toilet right on top of the boundary wall," showed Dr Jahan. "This happened even after multiple efforts at raising awareness."

Another photo showed a security forces camp built right on top of a Bhitargarh structure. One photo captured how locals were building an eidgah by clearing out the Bhitargarh boundary wall as a part of a government work scheme. More photos showed a desecrated column, a wall built on top of Bhitargarh's ancient boundary wall, missing bricks, monuments cut, cleaned and cleared. A map of the destruction of the site made by the researchers pinpoints mazars, mosques, hotels, poultry farms, irrigation channels, tea gardens, all built on top of the archaeological structures.

"There is even a temple underneath the village graveyard. The villagers routinely dig new graves there," stated Dr Jahan—acquiring this site would undoubtedly prove the most complicated.

Ironically, her first interaction with this site more than 10 years back was when she came across a woman cutting out a part of the boundary wall. "I asked her why she was doing that. She said she was taking bricks to lay out a new floor in her home," Dr Jahan described. She has had plenty such encounters since then with people attempting to destroy the heritage site.

It is of utmost importance that this site be protected and researched into because of how little information there is out there about Raja Prithu. "We find references to several rajas named Prithu beginning from the seventh century till the 13th century," stated Dr Jahan. "For example, the first king of the Khen dynasty that existed in the geopolitical entity of Kamrup (a region extending from north of Bangladesh to Assam and beyond) was one Prithu."

"Then there was another Prithu mentioned in a 13th century text called Tabaqat-i-Nasiri, but we are yet to find any inscriptions or archaeological evidence pinpointing which one was the king of Bhitargarh," added the professor, who also heads the Centre for Archaeological Studies at ULAB.

Tabaqat-i-Nasiri is a Persian historical volume written in 1260, and it detailed the life and exploits of a 13th century Mamluk emperor called Sultan Nasir Uddin. In that ancient text, Prithu Raja is recorded to have resisted the Islamic invasion from Central Asia, and it states that he had killed "one hundred and twenty thousand Musalmans." He was eventually killed by Sultan Nasir Uddin, the text states. An Assamese historian named Kanaklal Barua put the year of Prithu Raja's death at around 1228 AD, in a 1932 article called "Stemming the tide of Muslim conquest in India" published in the Journal of Assam Research Society.

There is yet another story about who Prithu Raja may have been, and how he died. In a book chapter written by Dr Jahan herself, and published last year, the archaeologist mentioned how noted British colonial surveyor Dr Francis Buchanan-Hamilton visited Bhitargarh in early 19th century, and recorded local tales of a Prithu Raja. Buchanan-Hamilton said that the king had died by committed suicide in order to save himself from a tribe called Kichak coming from the north.

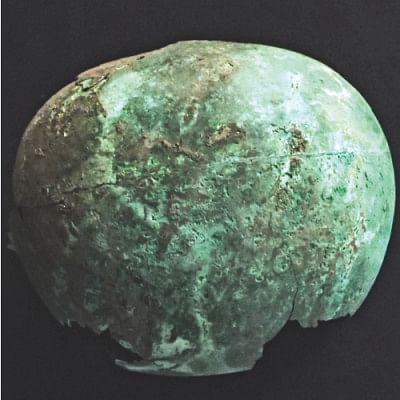

The research team led by Dr Jahan have found important artefacts like household items, and part of an idol of Vishnu—but more waits to be found. Perhaps the biggest thing yet to be discovered is who the king was, and during what time he reigned. To do this, the site needs to be protected and acquired. The question is, will the site get destroyed before the government gets to that point?

Comments