Hool Johar: Revisiting the eternal Santhal Revolution

One of the more insidious legacies of colonialism, that has by and large been accepted in the subcontinent, is the downgrading of stories passed down through oral traditions over many generations as either 'legends' or 'myths'. It is even more ironic since Bangladeshis, being a Muslim-majority populace, are the first to defend the Quran as untouched and a verbatim retelling of fact. A quick look through historical archives would point to the fact that the practice of disseminating Quranic scripture, too, was an overwhelmingly oral tradition which took on a written script many, many decades after its conception at Mecca. It's possible that we believe that the Arabs were a far more industrious group when it came to the task of memorising than the honey collectors of Sundarbans or the Khumi people in Chittagong Hill Tracts. While the Quran is pristine, belief of the Bonbibi (forest god) and the Bogley (water deity of the Khumi people) is apparently a myth that came about from some primitiveness in the other's culture. It's far more plausible, though, that we have collectively bought into the colonial practice of degrading the cultures and knowledge of indigenous and self-governing/self-sufficient communities as a way to disrupt and exploit their land and labour.

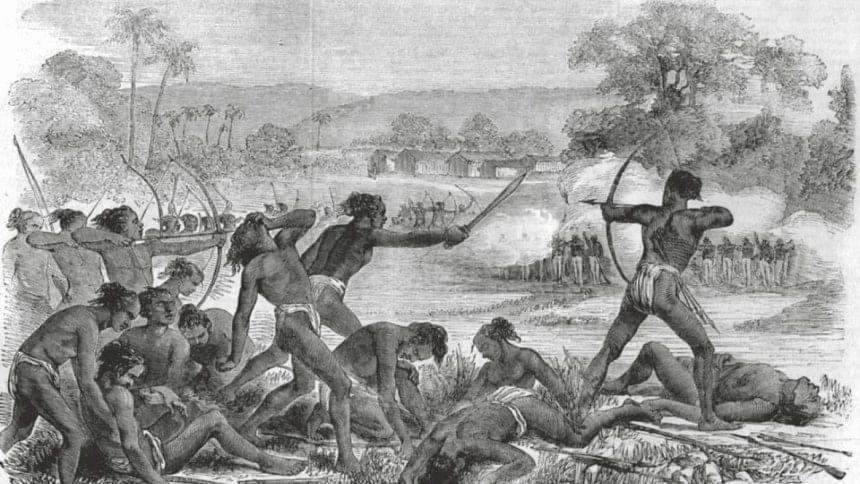

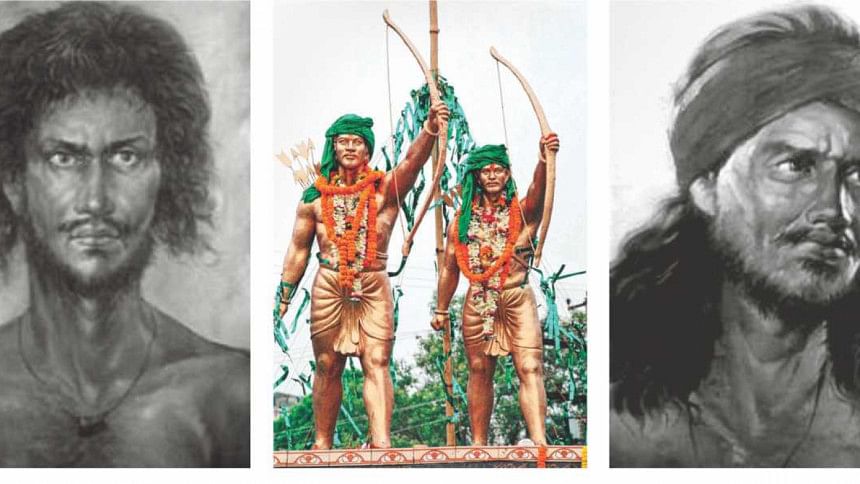

A very prominent example of this comes from the Bengali District Gazetteer on the Santhal Parganas, where it is stated that a popular 19th century Santhal 'legend' claims that two Santhals, Sidhu and Kanhu, proclaimed they had seen the vision of Thakur (Santhal god) who called upon them to evict outsiders from Santhal land. According to the Gazette, "The news of the miracle spread far and wide, and messengers were sent to all the Manjhi of the Damin-I-Koh bearing a branch of Sal tree, which like the fiery cross of the Highlands, was a signal to the people to gather together." This 'legend' became the precursor to what we know as the Santhal Insurrection or the Shaotal Hool of 1855 in the Damin-i-Koh region (present day Jharkhand) of the undivided sub-continent. The rebellion led to a calculated genocide by the British army who burned down hundreds of villages and killed and raped over 15,000 Santhals to quash their resistance.

What is curious about this rebellion, which marked its 162 years on June 30, is that it is to this day celebrated even in mainstream Bangladeshi society as one of the greatest resistances against the colonial government. As a hasty side note, it's mentioned that the rebellion was also against the colluding locals who acted as the zamindars and mahajans who unduly exploited the Santhal community. The narrative at once downplays the significant role that upper class and upper caste Hindus and Muslims played, and still play, in the exploitation of indigenous and self-governing communities, while at the same time it appropriates the rebellion into a nationalist celebration which culminated in the victory of communal politics and the Partition. Thrusting some credit of a disaster as large as the Partition on the Santhal revolutionaries is nothing short of a crime.

The Santhal Insurrection of 1855 was only the first recorded instance of a long history of rebellion that, to this day, reminds us of the role that indigenous and self-sufficient communities have played in liberation politics in the sub-continent. After the establishment of British rule in parts of Bengal and Bihar, the Santhals had already been displaced from their areas and brought to the politically demarcated region of Damin-i-Koh. With the Permanent Settlement of 1793, which gave clearly demarcated areas to zamindars, the British worsened the already bleak situation of peasants under this rent-seeking economy. The fledgling economy of talukdars, sub-talukdars and money lenders virtually destroyed any hope of agricultural sovereignty and sustainability by continuing to squeeze profit out of the peasants. Since 1792, the Santhals were forced into taking up various agricultural labour positions across all of Bihar and Bengal and this culminated in not only the formation of the Damin-i-Koh enclosure in 1832, but also the induction of thousands of Santhals into the construction of railways in 1854. Santhals were forced to become the embodiment of British appropriation as the orientalist William Wilson Hunter noted—"these Children of the Forest are ... amenable to the same reclaiming influences as other men, and that upon their capacity for civilisation the future extension of English enterprise in Bengal in a large measure depends". As the deeply entrenched bureaucracy and rent-seeking unleashed by the British got worse, the Santhals rebelled, led by the orders of Thakur, to reclaim their land from not only the zamindars and talukdars, but from the British Raj who made it all possible.

A history of indigenous rebellion

It's interesting to note that while the Santhal Rebellion of 1855 is celebrated quite openly in Bangladesh, the contribution of Santhals and other indigenous and self-governing groups is largely omitted from the history of sub-continental liberatory politics. One way in which this is done is by labelling the Santhal as primitive or 'simple and naïve' and removing deliberate agency and a coherent politics from their uprising. Orientalists looked at the genocide in Jharkhand and claimed it was a spontaneous reaction to poor governance, for which they lay the blame at the local culture of zamindari. Nationalists, on the other hand, appropriated it into their larger agenda of a sovereign nation-state by claiming that it was essentially what the Santhals wanted therefore in both cases, the indigenous struggle has been deliberately misrepresented to aid a larger majoritarian agenda. Is it possible, then, to look at the Shaotal Hool and other such uprisings without falling into this trap?

We can begin by looking at an excerpt from the Judicial Proceedings in the aftermath of the Santhal Insurrection, collected from Ranajit Guha's essay:

"The Thacoor has descended in the house of Seedoo Manjee, Kanoo Manjee, Bhyrub and Chand, at Bhugnudihee in Pergunnah Kunjeala. The Thacoor in person is conversing with them, he has descended from Heaven, he is conversing with Kanoo and Seedoo. The Sahibs and the white Soldiers will fight. Kanoo and Seedoo Manjee are not fighting. The Thacoor himself will fight. Therefore you Sahibs and Soldiers fight with the Thacoor himself. Mother Ganges will come to the Thacoor's (assistance). Fire will rain from Heaven… The reign of Truth has begun. True justice will be administered. He who does not speak the truth will not be allowed to remain on the Earth."

The reign of truth, which was called the Satyug, was a planned, deliberate and conscious rebellion by the Santhals to free themselves from the yoke of serfdom. What was dismissed as legend then, and still is today, is one of the few surviving historical documents that speaks to the subjectivity of the Santhal insurgent, that speaks to the bow of the Santhal that rained down arrows at an approaching horde of elephants and gunpowder. It wasn't a reactionary primitivism which compelled Santhals from all over the region to join the rebellion. Rather, it was the Santhals desire for self-governance which made the British so nervous and which they wanted to quash before it spread to the other peasants in the region. Indeed, to claim that the Rebellion did not get support from neighbouring non-Santhal peasants and lower caste groups would be inaccurate. Many non-Santhal groups aided the preparation leading to the Rebellion. Gwalas (milkmen) were among the many who gave them food and other provisions while the Lohars (blacksmiths) helped carve metal weapons for the insurgents. In short, there was a compelling unity across caste, ethnicity and, in some ways, class in the Santhal doctrine which led to the uprising; and it would not be inaccurate to argue that it bore the seeds of the formation of a deliberate, rent-free sovereign state which had the backing of peasants between the Ganges in the North and the Brahmini in the South. It was this that scared both Orientalists and Nationalists alike. Hence the liberal use of the terms 'legend' and 'myth'. Whenever traces of Santhal rebellion has surfaced since then, it has been met with prompt murder and brutality.

Over time, the Tebhaga movement of 1946 has been appropriated into the history of the communist left, owing much to the construction of Ila Mitra as the symbol of the movement. But we will do well to remember that Santhals had mobilised in the tens of thousands for one of the largest peasant rebellions in Nachol, Bangladesh, a century on from their rebellion in what is now Jharkhand. Like their British counterparts, the Muslim League responded with the characteristic response of a nation-state when it apprehends the demand for self-rule: rape and murder. The grand narrative of the Communist state dove-tailed with the visionary state-making prophecy of the Thakur carried forward by the likes of Jitu Santhal in Malda. And the memory of this promised state, carried in Santhal communities through oral traditions, was visible as recently as 1996. On November 5, 1996, more than 100,000 Santhals crossed the Indo-Bangladesh border and made their way to Nachol to welcome Ila Mitra back to the site of their struggle. It served as a powerful reminder to both states that their arbitrary borders meant little in the face of collective indigenous will. They turned up in their thousands to relive the times of revolution. Author Kavita Panjabi defined the event as 'Otiter Jed' (a rage from the past); that obstinate hold of a dream which has survived displacements and dislocations only to rekindle every century.

From the tea-workers' movement in Chunarughat (comprised of many Santhals) to the movement for land in Gobindaganj, the Santhal doctrine revealed to Sidhu and Kanhu and carried forward on the tongues of Santhal mothers and fathers still burns today. Re-appropriated history has blinded us to the immense organising potential that the Santhal movements have had in the past. Continued violence on indigenous and self-sufficient ethnic groups in the country should be a signal to those working on the left and in these groups to revisit these sites of knowledge as more than just 'myths' and 'legends' in order to form truly liberatory agendas.

*Johar: a term used as a greeting, or as a welcome, in areas such as Orissa, Jharkhand, etc.

Ahmad Ibrahim is a research fellow at Centre for Bangladesh Studies (CBS).

Sources:

Bengal District Gazetteer, Santhal Parganas, 1980:48-82.

Ranajit Guha, The Prose of Counter-Insurgency, Selected Subaltern Studies, 2002.

W. W. Hunter, Annals of Rural Bengal, 1897.

Judiciary Proceedings, 4 Oct. 1855: 'The Thacoor's Perwannah' for the Santal Hool.

Kavita Panjabi, Otiter Jed or Times of Revolution, Political and Economic Weekly, 2010.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments