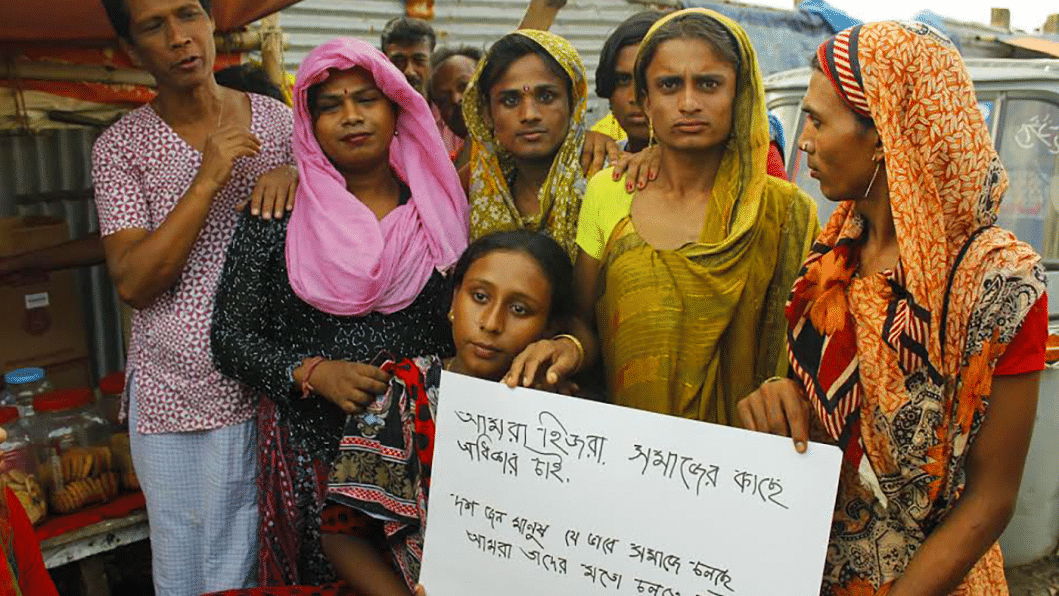

Leaving no one behind: “Hijra Lives in Bangladesh”

"When I was a volunteer for UNYSAB, a bunch of us were distributing sandals to rickshaw pullers who didn't have any. A group of hijras came along and took the sandals away, but a little while later, they returned and apologised for having done so. Assuming we were NGO workers, they said: 'Rickshaw pullers have parents, children, siblings, a family. We have nobody. Can't you do something for us too?'" remembers Nabeera Rahman, one of the Project Designers and Managers behind "Hijra Lives in Bangladesh", a photobook based on an ethnographic research into third gender communities all over the country brought out by UNDP Bangladesh. This chance encounter, barely a couple of minutes long, became the impetus for her and her colleague Jay Tyler Malette to apply for the RBAP Innovation Fund for this project two years back. It was an issue that needed more intervention, but they did not know what the hijra communities needed in the first place, so they decided to go to them and find out.

The photobook consists of a set of 40 micro-narratives collected from hijra communities in Dhaka, Chittagong, Rajshahi and Khulna. Together they form a life cycle portrait of the third gender, beginning in the early years of gender realisation and exile from society, encompassing the extreme exclusion they experience, and ending with their hopes of an empowered future.

The lead researcher, Bokhtiar Ahmed, Associate Professor of Anthropology at the University of Rajshahi, took a storytelling approach to the study. Unlike typical interviews, open-ended questions were asked and the women would talk uninterrupted. In the pre-consultation meeting, the hijras advised that one of them accompany the team while it collected narratives. "Otherwise, they would just say what we want to hear and would not be comfortable with us," Nabeera explains. This is how Tanisha Yeasmin Chaity became the first third gender consultant at UNDP Bangladesh.

Although an exploratory research, the team had some expectations of what they might find going into it. What struck them the most, however, was that they were not just dealing with income poverty. For example, Jahanara, one of the women interviewed in Dhaka, shares, "It hurts us that doctors don't examine us because we are hijras. Yet, they spend hours consulting the rich and at least some time with the poor." For hijras, even more than income poverty, it is social exclusion that deprives them of basic services.

"We talk about multi-dimensional poverty in slums, among impoverished men and women, but you very rarely hear about poverty in the third gender. Their poverty encompasses access to finance, healthcare, education, job opportunities, and more," explains Nabeera. We may hear a lot about hijras in relation to work with UNAIDS or LGBTQ rights, but not so much in relation to poverty, she adds.

We often simply do not want to associate with hijras or shoo them away, and in this way, they continue to be left out of the mainstream. While the government legally recognised hijra as the third gender in late 2013, on its own, it is not sufficient. As one hijra woman Nabeera and the team were working with put it, "Apa, eita kore amar ki hobe?" ("Apa, what use is this to me?") The woman lamented that a lot of money comes into the development sector, a lot of projects are started, and a lot of consultants are hired. They see the consultants move up in the world, but nothing changes for them. They are invited to speak at human rights events or are involved in development projects more and more, but not much has changed in the average hijra's day-to-day life.

During the launch of the photobook, Chaity, who also moderated the ceremonial session, asked the audience, "Koi jon hijra ke chinen apnar office e?" ("How many hijras do you know at your office?") She echoes Akhi, who lives and works in Dhaka: "Aren't women today doing men's job and vice versa? Then why can't hijras do the same?" The answer to her question lies in the many stories shared by several of the other women. Romana was employed at a hotel in Chittagong, but one day the owner asked her why she behaved in this manner. He wouldn't let her work unless she changed. "I couldn't explain that I don't behave like this intentionally," she says. Selina, also from Chittagong, was fired from the garments factory she worked in after they saw her woman-like behaviour.

But the women offer their own solutions in "Hijra Lives in Bangladesh", if only someone would listen. "If you accept us, then we would not have to do illegal and illicit works," states Tara from Rajshahi. Falguni from Chittagong dreams of opening a night school so that no one has to engage in derogatory work after dark. And Sonali from Dhaka thinks, "In order for us to obtain higher education, the educational institutes should be run by someone like us. Here the teacher should be from one of us. There are many educated ones among us who can do this with six months of training."

It is their voices, ideas, aspirations, and solutions that must be at the heart of the discussion. "I think the most important thing is to not just to involve hijras in the process, but make them design their own projects, do their own surveys, be agents of their own change. If a hijra cannot write a proposal, then she can certainly be taught these things, given these skills," believes Nabeera. And instead of portraying them solely as oppressed individuals, we need to focus on initiatives that are already employing and training hijras, and set an example for others, she adds.

The path ahead for the hijra community is anything but straightforward. There are conflicting views on a number of issues among the women themselves, while their gurus pose a different sort of obstacle. After they have left their families, gurus take up both the mother and father figures in their lives. Hijras are not only emotionally bound to them, but financially too. The gurus control their incomes and employ them in what they call "dark things", i.e. sex work. One of the hijras told Nabeera that their guru does not want them to be educated in fear of losing a source of income, but they do not dare do anything without the guru's permission.

Society is yet to acknowledge the multi-dimensional effects of gender-identity discrimination experienced by hijras. Whether it is getting a health check-up, renting a flat, or just using public transport, they are denied the most basic human rights for a life of respect and dignity. "Hijra Lives in Bangladesh" sheds some much-needed light on an extremely excluded group, but more importantly, shows how this very same oppressed community presents its own solutions. The one thing they ask for is acceptance.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments