SOS!

A glimpse into the lives of people stranded in the Geneva Camps has shown us the deplorable state in which they have been living for 43 years. Despite being shunned from the mainstream society, and abandoned by the government, these people have found ways to earn a bare minimum amount to stay alive. "There are only two or three main occupations, on which the entire Urdu speaking population is dependent," says Murtaza Ahmed Khan, Dhaka Correspondent of OBAT-Helpers, "Working in the karchupi (beaded-embroidery) business, hair salons and butcher shops. Others drive rickshaws, repair CNGs or bicycles or run small roadside restaurants," he informs us, "The few people who manage to get jobs outside the camp never get opportunities in the government sector. Even if we get selected for a job, the moment they find out we live in the camps they tell us we will go back to Pakistan so there is no point in employing us. The majority of our people do not have a formal education because our schools are not registered with the government, which makes it difficult for them to get into universities or get jobs in the private sector. Is it that surprising then that some go into the drug trade?"

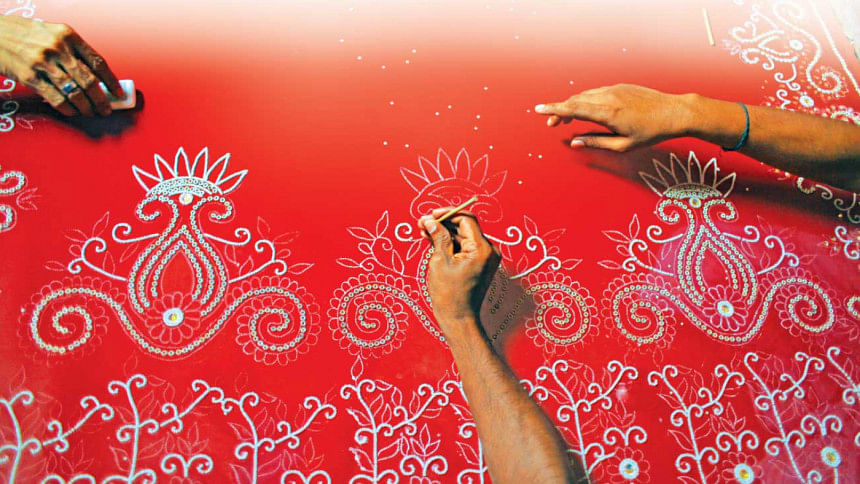

Those involved in karchupi work have a very small earning, "We supply our products to New Market, Mouchak, Gawsia etc. If a product sells for Tk 3000, the labourers only get 200-300 of that money each day. It takes us three to four days to make one sari because we do everything by hand," says Mohammad Armaan. "The prices keep going down because buyers are importing similar products from India, and very soon, we may be out of work."

"I support a family of seven on Tk 250 to Tk 300 a day," says Nurul, who has been working in a hair salon for the past 25 years. "I have to support a family of 7 on this salary and we are living hand-to-mouth."

"I managed to get a job as a CNG driver for while," says Abdul Gabbar, "Because my National ID has my Bihari Camp address on it, I was not able to get a driving license and the traffic sergeants harassed me every day. So I gave it up."

"There have been 3 agreements and one joint declaration signed between the Pakistani and Bagladeshi governments regarding our situation, but they are not being implemented," says Abdul Jabbar Khan, President of Stranded Pakistani General Repatriation Committee (SPGRC), "We are being kept like prisoners here."

In the Mohammadpur Geneva Camp out of 47000 people, only 20 to 25 have managed somehow to get their MA/MBA degrees. "Those who were born after March 25, 1971 were granted National IDs, but the backs of those IDs have 'Bihari Camp' stamped on them to brand us as outsiders. We are not even allowed to have passports," says Khan.

Currently, there is Rs 111 million, donated by Rabita Trust, saved in the National Bank of Pakistan in Islamabad, for the repatriation and rehabilitation of these refugees. "I have requested Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina, in 2008, to help us open an account here under the government's name, and transfer these funds to help us," says Khan. "I even said the government will have full control over the funds and how they are used. She had agreed at the time to do this, but nothing has been done yet," he tells us, "I am 75 years old and I worry about what will happen to my community when I am gone. After all these years of facing discrimination, we don't want to be Bihari anymore. We won't even ask you to send us away, give us a legal status, make use of us, and I promise we will become Bengali. There are 160 million people in this country, is it that difficult to make room for 3 lakh more?"

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments