Trump is now targeting families

Deportation of undocumented Bangladeshis from the USA is nothing new. In the last 10 years, the country issued deportation orders for 7,364 Bangladeshis. The period during Bill Clinton's presidency particularly saw over a thousand Bangladeshis being marked for deportation each year.

Deportation is a terrible—albeit legal—outcome for immigrants dreaming of a new life. But each administration has done it differently. Most of the Bangladeshis being sent back home during the Obama administration were men who came alone, leaving their families behind in Bangladesh. Research by Syracuse University also found that the Obama administration were mostly prosecuting people who had just arrived in the country.

In the case of the Trump administration, it is the exact opposite. Only 10 percent of the immigration cases being scrutinised by the Trump administration relate to newly-arrived people—meaning, a majority of the people being caught in the hook are longer-term residents of the US.

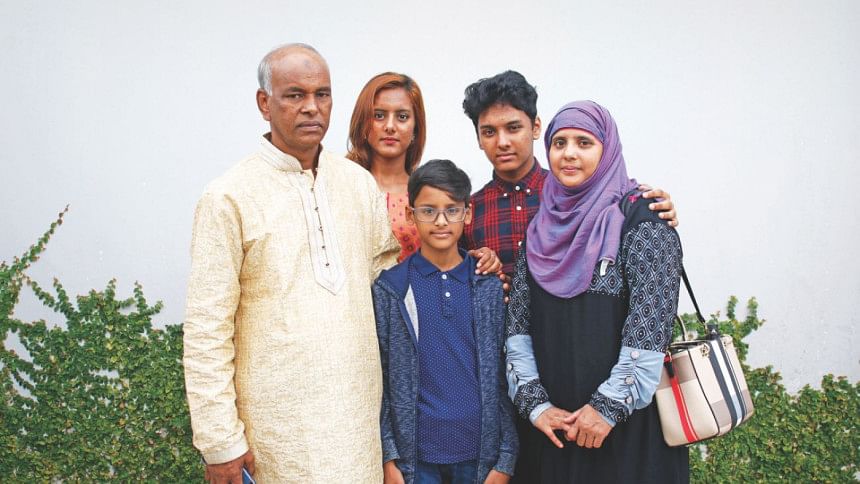

That is how Aminul Hoque and his family ended up back in Bangladesh 18 years after they had left it for good.

"Father was at work when two law enforcement men knocked on our door asking where he was," describes Evana Akter, Aminul Hoque's college-age daughter. Although they were dressed in plainclothes and never said who they were, something told Evana that the men might be agents of the Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE). She kept her cool and lied to the men, saying she had no idea where her father was.

That did not deter them from turning up at the eatery in the city of Newark of New Jersey state where Aminul worked.

"About 20 minutes after I closed the door on them my mother called me up and said my father had been picked up," says Evana.

Aminul continues the story from here. "I was taken to jail as a prisoner. They were executing a deportation order issued against me. My lawyer said she can try to get a stay on the order but there is no guarantee that I will be let out of prison," he says. So he accepted his fate of being sent back to Bangladesh. It is, after all, better to be sent back than be in jail.

Aminul's home country's general stance is that immigrants who are staying in any country without documents can be deported back to Bangladesh because it is in the law. Even though immigrants return home every year there is hardly any national discourse on their plight or their rights. Pick up any North Jersey newspaper or news website, it will have blow-by-blow coverage of the journey of Aminul Hoque and his family as they navigated the deportation procedures. Local immigration rights support groups formed human chains to demand the family be allowed to stay back.

Their home country, the country that earned 7.24 percent of its GDP this year from remittances sent from abroad by workers like Aminul and his wife, never said a word.

In Bangladesh, the lack of any activism or advocacy surrounding deportations of people like Aminul stems from the idea that being undocumented is a criminal act. This assumption shows a lack of understanding for the complexity of immigration procedures. Aminul Hoque used to be a Jatiya Party supporter and eked out a living by working as a contractor like most people involved in party politics. He fled to South Africa from Bangladesh after 1996 when Bangladesh Nationalist Party won the elections. Then he, along with two of his brothers, bought a shop in Botswana where Aminul lived for several years as a proud shopkeeper. "We expanded to four corner stores and business was doing well. Twice a week we participated in a flea market," says Aminul. His wife gave birth to Evana, and then three and a half years later, to a son. All this changed when his shop was broken into.

"It was a very unsafe neighbourhood. I wanted to move my children somewhere better," says Aminul. So he and his family joined his sister in the USA in 2004 and applied for political asylum. These procedures are lengthy, during which time families build lives in USA—for example between the time Aminul applied for asylum and his final removal, his children had grown up and the family had a third son born to them.

"My asylum application was affected by the fact that I had travelled back to Bangladesh this one time to see my ailing mother," says Aminul. People applying for asylum have to prove that it is impossible for them to live in their home country and lawyers often suggest that making a trip back home while the application is underway can weaken the case. For giving into the urge to see his mother once in 18 years, Aminul's application was jeopardised.

Also undocumented or not, the family got yearly work permits and paid their taxes, meaning they contributed to the US economy. These taxes were basically money down the drain because undocumented persons do not qualify for any government benefits like social safety programmes. The family classifies as low-income, but was not eligible for any help from the government. Only their youngest son, who is a citizen, received food stamps for himself which the family of five shared.

Demanding that immigrants legally reside in a country, or suffer the consequences alone, is a denial of the reality that hundreds of thousands of Bangladeshis live and work as undocumented residents across the world. Exact numbers are difficult to find because undocumented people rarely enter the system for fear of being deported. An example, however, might give some idea: in 2015 the city of New York gave identity cards to 50,000 undocumented Bangladeshis—50,000 was simply the cap set by the city and does not reflect the actual number of undocumented people. Also to note—this was in one city only. Aminul's state of residence, New Jersey, houses an equally sizeable Bangladeshi population.

A cold impassive wall greeted the family when they arrived in Bangladesh. "How do I start my life all over again?" laments Aminul. "I only have Tk 3 or 4 lakh in savings. I am currently residing in my brother's home in Siddhirganj. How can I get a job here after all these years?"

Aminul Hoque used to fry chicken at a joint in Newark. "I also used to supervise the other cooks," he adds. His wife Rojina Akhter quickly adds, "Yes, yes he was not just frying chicken... and I was a cashier in a 99 cents store but I was the main cashier." Hers was a part-time job.

Frying chicken and manning cash machines in Siddhirganj will hardly allow the parents to earn enough to send their children to the kinds of schools they need to realise the future they were promised in USA.

"How do I gather the money to admit my children to good schools that will give them the same quality of education they were getting in New Jersey?" asks Aminul. He fears that the children would not be able to adjust to the public schooling system having limited aptitude in Bangla.

Of the three of them, the middle brother stands to lose the most—a current tenth grader, he hardly has any time left under his belt to orient himself to public schools. The two older children are not American citizens because they were not born there—they are just as undocumented and unwanted as their parents.

"I have never committed any crimes. Then why was I deported?" asks Aminul.

Immigration data shows that of the 1,114 Bangladeshis against whom deportation proceedings were filed in immigration court in 2018, only nine committed actual crimes. Two of these nine were aggravated felonies, which can include offenses like not showing up to court—this hardly qualifies as an immoral act.

"Generally, ICE's policies are really inconsistent. Who they want to remove and when, is at their discretion. Families were not targeted as much before," says S Nadia Hussain, a Bangladeshi-American social activist who worked with the family during their time in New Jersey. Hussain runs an organisation called Bangladeshi American Women's Development Initiative and had tried to get the local government to intervene in Aminul's case.

"Deportations can be stopped if local administrations step in," says Hussain. She gives the example of Syed Jamal, the Bangladeshi chemistry professor from Kansas who came into media spotlight earlier in the year for the deportation order against him. "He was in the same flight back to Bangladesh as Aminul but was dropped off at Hawaii because of pressure from the community." Jamal has been a resident of the US for 30 years, taught at universities in Kansas and Missouri and has three children.

Of Aminul's family, only the youngest son can legally go back to the US rightaway since he is a citizen. But the thought of leaving him alone under the care of a foster family is unthinkable to his loved ones. "Me and my brother could have also stayed back under special provisions since we were taken to USA as children. We would have been exempted from prosecution," says Evana, "but we did not want the family to separate." And rightly so, because deportation means Aminul will not be able to go back to the US in the next 10 years.

Aminul's is one of the first families to be sent back to Bangladesh by the Trump administration but if the data says anything, they will hardly be the last. The question is, are we prepared to rehabilitate them?

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments