All the talk, we talk

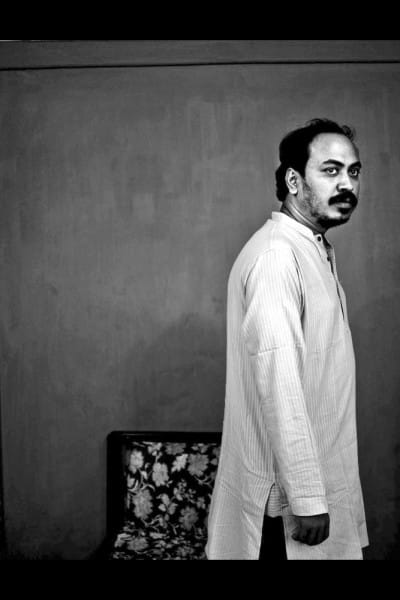

Many may know Shibu Kumer Shill as the lead singer of Meghdol, a popular soft rock band; some may know of him as a book cover artist who skillfully merges the contemporary with the traditional. Shibu Kumer Shill is also an up and coming author. He has previously written one book on poetry and has very recently launched his second book, Kotha Jata, a compilation of interviews of visionaries in the field of arts, literature, and cinema in Bangladesh.

The book, officially launched on April 19 this year, has six interviews conducted between 2008 and 2013. The original plan had been to make documentaries but as Shibu worked through the interviews, he realised he wanted them to see the light of day sooner.

The author sat down with Star Weekend to talk about the book and his inspirations.

SW: Tell us a bit about the book and what made you choose these particular interviewees?

I interviewed these particular people as they represent a particular time in history. Their work and those who they talk about have shaped cinema, arts, and literature as we know it today. For the literature category, I talked to Abdul Mannan Syed, a renowned writer, about his friendship with Akhtheruzzaman Elias, a veritable legend of Bangladeshi literature. In the same category, I interviewed contemporary writer Shahaduzzaman, on the techniques and politics of his writing. In the arts category, I interviewed writer Hasnat Abdul Hye about his novel on sculptor Novera, and Charukola teacher and artist Nisar Hossain on the relevance of Novera. For the cinema category, I interviewed Humayun Faridi, who revealed stories of his life and his philosophies. I also interviewed Nurul Alam Atique, who talks about his cinematography and his stories and why he felt compelled to showcase the middle-class and their struggles in this city.

I felt this documentation is important to those who aspire to work in these particular fields or would like to research these topics, before these people and their stories are lost to the world forever.

SW: You said this book was designed as a dialogue rather than as an interview? What differentiates these styles for you?

Shibu: Of course, this is an interview process. But in most cases, I was able to move on from just asking questions to actually engaging in dialogue. In the case of Humayun Faridi, however, I failed completely. I could only question him but could not probe his answers further. If I tried to interject, he would lose his flow of conversation. If I consider him my protagonist, then I can say for sure, I could not deal with my protagonist; rather, he played me. But I was able to have a dialogue with Nurul Alam Atique and contemporary writer Shahaduzzaman. In the case of veteran writer Hasnat Abdul Hye, who is a very senior artist, I could not really confront him as much as I might have liked to on the issue of his novel about Novera being extremely patriarchal—I could not create that space. That is why I have said that some are dialogues and some are simple interviews.

SW: You dedicated two interviews to the country's first female sculptor Novera Ahmed. What issues did you explore in those interviews?

Shibu: I have interviewed the first person to have written a book about sculptor Novera Ahmed, Hasnat Abdul Hye. That book was written from a very male chauvinist perspective. But had he not written the book, maybe the dialogue on Novera would not have started at all. But I had to ask him why he wrote from this gaze and what prompted him to write about Novera. In the interview, he reveals that he was inspired to write about Novera because she roamed many countries and lived a carefree, and sometimes controversial, life despite being from a Muslim family. Not all the questions I asked him are necessarily answered in my interview, but at least we take a look back together. I also interviewed Charukola professor Nisar Hossain who talks about Novera's significance for today's generation.

SW: Let us talk about Nurul Alam Atique. Everyone wants to know and often inquire why there is such a long time gap between his work. How come you did not ask this particular question to him?

Shibu: When it comes to audio-visual fiction, Nurul Alam Atique is an individual school in his own right. From the very beginning, Atique has shown his magnificence as a storyteller, but in his movie Dubshatar, we really get to see Atique's prowess as a director. We see the city from his lens, and his character comes through in the moviemaking process. It is a story of a middle-class man, who worries about what to have for breakfast. It is a story of a woman, who gets pregnant and wonders what to do with the child. All in all, the originality of Atique shines through in the movie. So, I ended up talking to him more about his work rather than about his hiatus from the industry. It was after all his personal decision and I did not feel compelled to probe into those reasons.

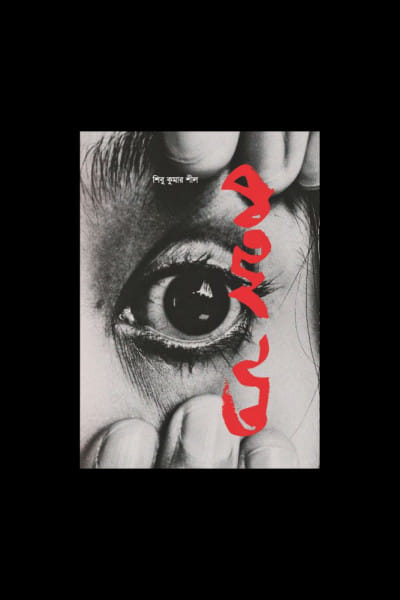

SW: You are quite well known for your illustrations on book covers. Tell us a bit about the cover of your own book, which we can see is inspired by Andalusian dog. How does it connect to the content?

Shibu: Usually when an artist draws a book cover here in Bangladesh, s/he takes inspiration from the content in the book. But I believe that the cover can be an individual content, and the story within the book, another individual content, and they can all come together to form one coherent story. In this cover, for example, is an eye that is being forced wide open and when you open the whole book, there is a saw wrapped in red string indicating violence. What does an eye indicate? It is forcing us to look around. Even if I do not want to see something, I am compelled to. Within the book, there are stories of violence, especially in the interviews of Nurul Alam Atique and Shahaduzzaman, and one way or the other, this comes through in the cover.

SW: What is the significance of cityscapes when it comes to your protagonists?

Shibu: Maybe I am obsessed with the city life but I did not intentionally incorporate those themes into the book. But because of my obsession, I think my subconscious ended up portraying characters or stories with a strong pulse of a city in the book. Each of the characters who take turns narrating their own or someone else's story reveal an integral element of their lives, navigating the city, be it Dhaka (both old and new) for Humayun Faridi or Chattogram for Shahaduzzaman. I do not want to hide this obsession with a city. It wasn't a conscious decision. But I believe that cities and its subjects get intertwined, and I have always carried within me an admiration for cities and their ever-changing faces. Maybe that is what comes through in the writing. Because these interviews aren't always just what my subjects told me, they are also a reflection of my own thought process.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments