The Bangladeshi migrant worker turned award-winning writer in Singapore

Migrants are often said to have built the imposing city of Singapore, making up around a quarter of its workforce, but are arguably not yet considered part of Singaporean society. For migrant worker Md Sharif Uddin, that he would have a book published in Singapore and win an award for it at a ceremony where he was seated on the very chair Lee Kuan Yew used to sit, was unthinkable.

Sharif was an avid reader during his school and college years. "I used to read a lot but never thought I'd write. I always wrote a diary though," says Sharif. A fan of Bangla writers such as Rabindranath Tagore, Kazi Nazrul Islam, and Bibhutibhushan Bandhyopadhyay, his first serious job out of college was running a small bookstore in Rangpur, where his family moved in the '90s.

Sharif would keep another copy of a book he was reading at home, at the store. "I would continue reading it at the store and then pick up the same book again at home. This way I read many books." After the building Sharif Book Corner was housed in was declared illegal and demolished, Sharif suffered losses and started looking for a job abroad. He settled on Singapore because it offered a legal path to securing a job and a work visa.

The 40-year-old trained as a welder and went off to Singapore as hundreds of thousands other Bangladeshis have over the years for low-wage jobs in construction. His initial diary entries were of his job, his first foray into construction work, and writing about his life as a migrant worker in a new country. Sharif also began writing about other migrant workers, with whom he worked and lived.

In 2013, a local Bangla newspaper, Banglar Kantha, read mainly by the migrant worker community, put out a call for submissions from readers. Sharif submitted a poem. Until then, his writings on migrant life had been posted on Facebook for which he tailored short write-ups. The editor of the newspaper, impressed, called asking for more of Sharif's writings. He started regularly writing a probashi diary of short stories and poems based on his own and his fellow workers' lives, experiences and feelings.

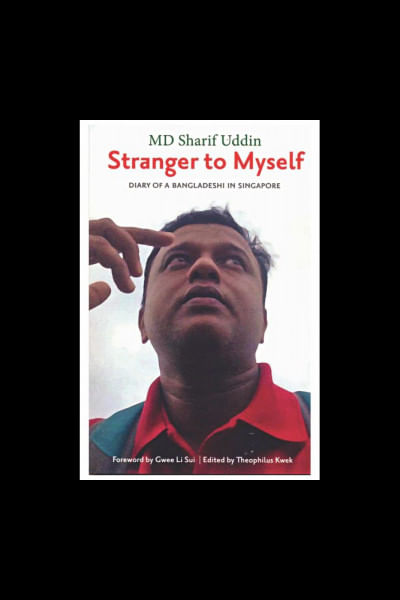

One common theme running though their shared experience was leaving behind family members in Bangladesh. Sharif himself left behind his pregnant wife in 2008; his son is now nine years old. Other points of reference were the city of Singapore and what the workers had expected and what they eventually experienced, and about the agents who brought them there and how they had treated them. These diary entries and poems, numbering over a hundred, were eventually translated and compiled into a memoir Stranger to Myself: Diary of a Bangladeshi in Singapore in 2017.

Sharif went on to compete at poetry and short story competitions specifically for migrant workers, which brought him into contact with the local literary scene. Though Sharif writes exclusively in Bangla, he held onto the dream of publishing in English. "If it remains in Bangla, no one will read these but us. I wanted to publish my accounts of migrant workers' lives in English so that the local community here understand our lives and the problems we face."

As luck would have it, around when he stopped writing his diary entries in Bangla, Sharif received a message from a local publisher, Landmark Books, asking for some of his writings. Sharif had a Bangladeshi acquaintance translate several diary entries and poems and sent them in. At that point, Sharif had amassed 300 such write-ups all while at his full-time job.

On encouragement from the publisher to send in more entries, Sharif readied about 120 entries. He didn't yet know that these were intended for a book, though. When he did, he was excited but also frustrated by the process of bringing the book together. "I was heavily smoking at the time, wondering if my book would ever happen. If it was released, I promised to give it up," he remembers, laughing. He quit after over 20 years of smoking.

As the book came together, Sharif was asked where he would like his book launch to be held. His first and only choice was the National Library building, where Sharif and his friends would often have adda in a space which offers a panoramic view of the city. Though there were no openings that month, a lucky cancellation made Sharif's dreams come true. Almost a hundred books that were displayed at the launch, sold out. "People lined up to take my autograph and photos with me."

"I never thought my own book would be published, that too in Singapore, and in English." He has been feted by and is now a regular at Singapore literary events such as the annual writers and poetry festivals and done readings everywhere from the National University of Singapore to the Kinokuniya bookstore. Stranger to Myself can now be found in public libraries across the city-state.

Sharif rarely gets the time off to attend these though, with a demanding job. The morning we talk over the phone, he had just come off of a 12-hour night shift. In other ways, too, his life as a migrant worker remains unchanged. He rooms with roughly 30 other workers in a company dormitory where he is bused to and from work shifts. Sharif would take out his notebook or type away on his phone on the bus commute home from work, which takes up to an hour and a half.

"I don't necessarily consider myself a writer or a poet because I don't follow rules of verse and my writing is very personal." He explains that as a worker himself, it is easy for him to understand other worker's experiences, and so writing these are not difficult for Sharif.

In November last year, Stranger to Myself was awarded best non-fiction at the Singapore Book Awards held in the old Parliament house chamber. Sharif had dedicated the book to Lee Kuan Yew, the founding prime minister of the country he had spent most of his working life in. To his great delight, the organisers had something special in store for him. "When they told me I would be seated at the very seat in which Lee Kuan Yew would sit while in Parliament, I decided I would most definitely miss work to attend." No Bangladeshi had ever been even nominated, much less won.

Sharif's fellow workers and company management weren't even aware that he wrote, so much so that a visit from the Ministry of Manpower following his book launch scared management that he had been doing something subversive or badmouthing the company in his book.

As Sharif puts it, there is little to no corruption in the tiny state of Singapore. While migrant workers in low-wage employment are not outright abused, they face difficulties regardless—including being bound to a particular employer, unpaid salaries, and debts to agents who brought them there.

As a safety supervisor, Sharif saw firsthand some of these problems, not limited to workers but also of their companies—issues he brings up in his book. "For instance, the ministry [of manpower] would announce visits beforehand, allowing management to make the site 'safe' beforehand," says Sharif. The work most often fell to him to secure the site before such visits.

Sharif also writes about other concerns of workers such as how little workers' time is valued. The workers have to take the bus at 5am in the morning when their shift starts two hours later. "If my time is wasted because of the company, they should pay me for it," he points out.

A published book and a major award later, he says he feels pride that he fulfilled his goal of letting people know how workers like himself live, eat, work, feel, and suffer in the country. Still not earning enough to upgrade his work permit and have the option of bringing his family to Singapore, Sharif dreams of how much more he could achieve if he didn't have to work full time.

Back in Rangpur, Sharif's Book Corner, now run by his younger brother, has a copy of its namesake's book.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments