All Talk And No Walk

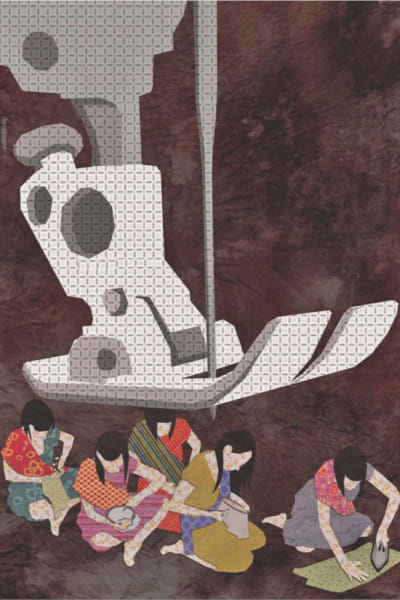

One morning, I read an article, published in one of the most widely read newspapers of Dhaka, suggesting that all the negative news on garments sector of Bangladesh, overplayed in the media, damages not only the owners but the workers too, that one New York based report is all but misleading, and that reports and media coverage don't change the ground reality. In the afternoon I decided to enter into a Garments factory in Mirpur area. A small factory with four hundred workers. My objective was to inquire about the status of maternity benefits and what exists in practice.

Before the meeting I, along with a research partner, visited some of the workers who lived in the factory's vicinity. We simply asked if women working in the factories enjoyed any maternity benefit as postulated in the labour law. The answer was no. In fact, the answers were more complicated than a simple no. Someone said: "It is difficult to get a leave for sickness, let alone maternity benefits." Instead of answering my questions, some complained about the unfriendly work hours that last till 8:00pm. It is not that the workers we met did not know about the maternity benefit provisions but they claimed that the benefits were simply not provided. We met female workers who are now working in other sectors but had been employed in the garments sector in the past. After much cajoling, they told us that they have not seen anyone availing maternity benefits themselves, but could name a few factories that did offer these benefits while also saying that they could name others that did not.

We then visited the factory, and in the five minutes it took for the compliance officer to greet us, I took in the area around the entrance. They had a doctor's room full of cartons and packets, a reception room with a misspelled sign and stacked with boxes and assorted items. The passage through which workers were exiting was also clogged with boxes. The security guard's ever-wary eye did not allow us to snap pictures and I was also slightly unsure if the visit would be a fruitful one as I did not know anyone in the factory.

A young man in his late twenties took us to his office, where his office-mate was busy ticking off the attendance (hajira) bonus cards. It was almost 6:00pm and the factory seemed to be operating full swing. We noted some bananas stored for the workers' tiffin break. The young man with two large computer monitors on his table claiming to be the compliance officer turned out to be a Titumir College accounting studies graduate. He had joined the factory very recently. I began by asking if the workers get maternity benefits as stipulated by the law. To my surprise, he said that the workers do not demand any such provision. Usually, when they are pregnant, they resign and leave the factory "on their own".

His statement that workers resign on their own sounded odd. He said he had not seen anyone taking leave, and that there was no record of such leave on the register.

But then what is the policy of your factory? Do you have a maternity benefit policy? He answered in the affirmative, but when I asked what it was, he seemed unaware. When asked if he could show us the policy, he brightened up and showed us a shiny new, hardly used file in which the maternity policy was spelled out. He was somewhat quick to point out the relevant policy page of the file, but when I asked if he could tell me what the policy was, he seemed at a loss. Then again, if no one had asked for maternity leave, perhaps his unpreparedness was justified!

I took a picture of the brand new maternity leave policy and left the building somewhat distraught. My research collaborator, who was mostly silent during the meeting, quipped: "Everything here exists on paper. All the right signposts are there and whatever disorganisation there is will be papered over on the day of the buyer's visit. But for the rest of the year, things will remain disorganised and shabby. In the midst of all this I even forget to ask if there is a day care center for children of working mothers. Perhaps they have one 'for show', as the workers often say."

The next day a graver scenario emerged when we talked to some more people outside the factory. Of course, there were some who were unwilling to talk to us, especially in public spaces, with many saying that they feared losing their jobs. One of those who were happy to share their experiences was Zamila, who had worked in the garments sector in various capacities for the past 17 years. Although she started out as an operator, after some years it became too arduous for her. She could not continue in the position because of constant back pain and eventually opted for a less prestigious role as a cleaner

While gutting fish in her one-room house in Mirpur, which she shares with her husband and son, Zamila talked to us about her experiences. The family was from Barguna but was living in Dhaka for 17 years and did not know when they would return or if they would return at all. When asked about maternity benefits, she was very clear that maternity benefit is not given to 'buas'. For the operators and others in the factory where she works, the benefit is given for two months and after the child's birth, the workers join the factory and work even when they have to breast feed their babies.

Pregnant women face immense difficulty in factory work during pregnancy. They are susceptible to various health issues and this makes them vulnerable in their workplace. As one activist in Dhaka who has substantial experience of working with working women put it, once they are pregnant, they tend to be afflicted by the fear of losing their job.

We met a worker in Narayanganj who was advised to leave the job and return after childbirth by the factory's compliance officer. Instead of receiving benefits, the worker was advised to resign for the sake of the newborn as she was facing difficulty during her pregnancy period. She was recruited again after childbirth as a new worker with the same basic salary.

Of course, we also met people who would tell us that compliant factories were different, where there exist better practices. For example, there is a separate dress code for pregnant workers in some factories. Often, pregnant women are also exempt from heavy work, and weight-lifting, etc. But generally, workers told us that a lot of these factories were very strict about allowing sick leave, and that the management were keen on deducting salary for any casual/unreported leave.

A 16-week maternity benefit is now stipulated in the labour law of Bangladesh. For government departments, this has been extended to six months. The workers whose narratives I picked up are people whom I met randomly. Perhaps a door was open and we decided to talk. Perhaps someone looked a bit inviting, so we stopped to discuss. The factory too was picked at random. This accidental methodology also paints a picture and a reality which perhaps is not very unfamiliar to those who live in Bangladesh. I hope the government's regulatory bodies, buyers and other concerned bodies do the same and see what is there in practice and not just on paper.

Mahmudul H Sumon Ph D is an Associate Professor of Anthropology, Jahangirnagar University.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments