Sexual harassment of RMG workers

Women's participation in the ready-made garments sector, and the importance of this sector to national exports and economic growth has contributed to changed perceptions of women's economic and public role and has provided women themselves with more options.

The increased participation of women in paid work both outside and inside the home has now brought to the fore issues of their safety and security in the workplace and on the commute to work. Violence and sexual harassment in the workplace are not new issues but are now recognised as critical enough that International Labour Organisation (ILO) is preparing an international convention against sexual harassment at the workplace.

Women's labour rights are protected by law. Through the revision of the Labour Act, 2006 in 2013 and formulation of Labour Rule in 2015 the rights of workers were addressed and initiatives taken to ensure a decent work environment. This included workers' right to trade unions, introduction of an insurance scheme, setting up of a central fund to improve the workers' living standards, and requiring 5 percent of annual profit to be deposited in employee welfare funds. The recent Labour Rules also have introduced detailed specifications for provisions such as child care and compensations. The National Industrial Health and Safety Council has drafted an Occupational Safety and Health Policy which remains at the final stages of approval. The implementation of this policy would benefit women more than men as they are more affected by its absence.

The Labour Code, 2006 and its revision in 2013 recognised the issue of sexual harassment in the work place. The High Court judgement on sexual harassment also provides guidelines to employers and educational institutions on how to address sexual harassment issues.

However there are still various barriers and constraints to women's participation in the labour force, especially in paid work outside the home. The kinds of work available for women do not meet their expectations and are sometimes demeaning and poorly paid; there are strong cultural and social constraints to outside paid work; and working conditions, safety and security in the workplace, housing and in public spaces on the way to and from work are often concerns for women entering the labour market and their families.

Violence and harassment against women is a global human rights problem.

Many women become victims of violence and harassment in their daily lives in both public and private spheres. Patriarchal social and cultural norms often exacerbate the violence and abuse. At the same time, there has been growing recognition that countries cannot reach their full potential as long as women's participation in the social and economic realms remains limited. Though it is difficult to accurately assess due to underreporting, violence is prevalent across all social and economic groups in Bangladesh's rural and urban areas. In addition to the high direct costs of violence against women in the form of health care, displacement, social service, legal service and criminal justice, there are also economic and social multiplier effects in the form of reduced productivity and inter-generational impacts of violence on children.

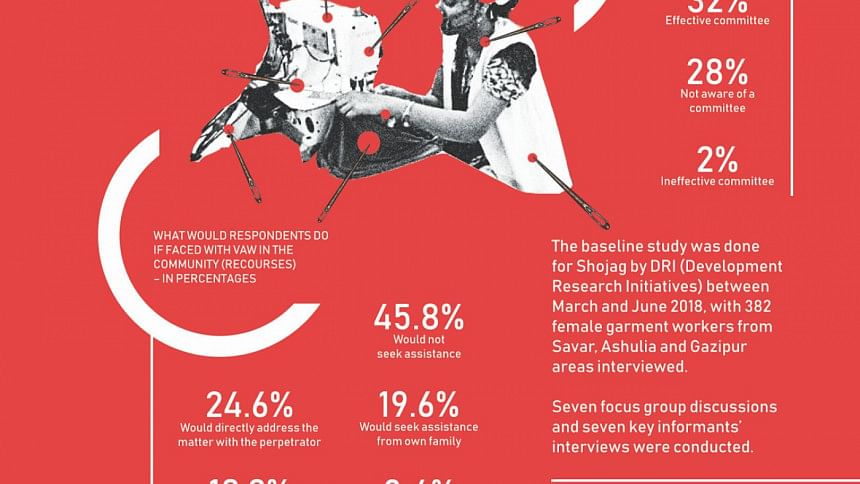

A baseline study was carried out for Shojag* by DRI (Development Research Initiatives) between March and June 2018, with 382 female garment workers from Savar, Ashulia and Gazipur areas interviewed. Half of them were from factories with which the Coalition has entered into a memorandum of agreement to work together. Seven focus group discussions and seven key informants' interviews were conducted.

85.1 percent of the respondents mentioned that their workplace was "women-friendly" and 75 percent of the staff mentioned that staff were fairly treated, but only 49 percent mentioned that they had not experienced verbal abuse; only 43.1 percent mentioned about no sexual harassment and only 22.7 percent mentioned that they had not experienced mental harassment.

22 percent of survey respondents (85) experienced violence or sexual harassment in the workplace or on their way to and from work. 80 percent of the 85 faced verbal abuse (offensive language); 41 percent faced verbal sexual harassment; 22 percent were inappropriately touched by male colleagues on the pretext of work assistance/guidance: 12 percent were harassed by phone/text; 6 percent faced sexual harassment during commute; 5 percent experienced offensive/sexual solicitations on the way to/from workplace and 4 percent experienced corporal punishment (beating/slapping etc.). Some forms of violence are common in both workplaces and public spaces. The role of new technologies is shown in the prevalence of harassment by phone calls/texts (proposal for affairs/marriage/verbal abuse etc.; intimate picture/video [of victim] posted on internet (revenge porn etc.).

The baseline sought to understand what measures women or men would or could take in the case of incidences of violence. 85 percent of the respondents said they would complain to garment factory officials (manager, welfare officer, HR officer etc.) in a case of VAW; 15 percent would use the factory 'complaint box'; 20 percent would seek assistance from the family;13 percent would directly address the matter with the perpetrator; 11 percent would complain to the Sexual Harassment Complaint Committees; but 12 percent would not seek assistance at all. And only 1 percent each would seek legal assistance or go to the police.

There seems to be a strong confidence in the system with 80 percent indicating that they would get adequate responses. 32 percent of the respondents know about Sexual Harassment Complaint Committees in workplaces and find them effective; 2 percent of the respondents know of such committees but find them ineffective; and 28 percent are not aware of such committees and the remaining 38 percent said that there are no such committees.

However, if incidents happen in public spaces there are less avenues for recourse open to women. 46 percent of the respondents said that women would not report cases of violence if the violence occurred in public spaces. 25 percent would directly address the matter with the perpetrator; 20 percent would seek assistance from their own family; 10 percent would complain to garment factory officials. 9 percent would file charges against offenders with the police station or other authorities and 2 percent would threaten legal action against the offender. However, very few would seek assistance from Government legal aid services or from trade unions.

Seventy-seven percent of the respondents were aware that there are criminal laws to punish the perpetrators of VAW. And 94 percent of the respondents agreed that VAW is a punishable offence. However there was a lack of clarity about the penalties. The most common sources of knowledge about laws are word of mouth (90 percent).

The study highlighted the need for a coordinated and holistic response to violence faced by women in the RMG sector with Government, employers, trade unions and NGOs having roles to play in eliminating this violence. These are briefly discussed below.

The Government is the main actor who can ensure implementation of 2009 and 2011 High Court Directives on Sexual Harassment in RMG industry through the Directorate for Inspection of Factories and Establishments (DIFE). It can encourage employers to activate complaints mechanisms and monitor that these mechanisms deal with cases in a fair, confidential and timely manner.

Regarding violence happening in public spaces and on the commute to work the Government can provide opportunities for workers to bring complaints about violence and sexual harassment in public spaces, on the way to and from work and in public transport through local government bodies. It can educate workers on municipal services and roles of locally elected representatives and law enforcement authorities in preventing and providing redress in cases of violence and sexual harassment. The Government and local administration and local government bodies can take measures to increase safety and security of workers on roads and public transport on their way to and from work by ensuring adequate street lighting, usable foot-paths and regulated public transport through local admin and local government bodies.

The Government can make public transport owners and workers more aware of violence against women and sexual harassment and their responsibilities for its prevention and redress. It can also have nationwide media campaigns to increase awareness of violence against women and sexual harassment as offences and of available prevention and redress measures such as Legal Aid Committees and hotlines.

Employers have a role to play to ensure that all RMG factories establish and activate Sexual Harassment Complaint Committees in compliance with the 2009 High Court Guidelines. They can facilitate the development of capacity of Participation, Grievance and Workers' Health and Safety Committees so that members are aware of their roles and responsibilities and issues brought to these committees are dealt with in a timely and transparent manner, including complaints of harassment and abuse. Management should encourage workers to use formal complaints mechanisms and allow formal complaints mechanisms to deal with cases in a transparent and timely manner. It is a sign of a strong management if complaints can be made and dealt with properly and not suppressed or dealt with informally. As preventive measures awareness among factory management and workers of the importance of having a violence free workplace in compliance with the Bangladesh Labour Law and other legal requirements, should be increased. The understanding among factory management and workers of nature of violence against women in particular sexual harassment, its consequences and available penalties should be ensured.

Employers also have a responsibility to promote safety and security of workers in the industrial areas which means taking necessary measures in collaboration with local administration and local government authorities to ensure safety and security of workers on the way to and from work, and not just in the factory premises. This could also include providing legal and psycho-social counseling and support to workers subjected to violence and harassment outside the factory. There is also a need to increase jurisdiction of the Sexual Harassment Complaint Committees to hold employees liable for off-duty conduct i.e. for acts of violence or sexual harassment against fellow workers committed outside the factory.

Trade Unions as associations for the protection of workers' rights should incorporate the agenda of violence against women in the workplace or on the commute to work as part of their core agenda in tripartite negotiations and trade union activities. Awareness among TU leaders and workers of the importance of a violence-free workplace as a part of legal compliance with the relevant laws and judgments, should be increased. Understanding among TU leaders and workers of violence against women in particular sexual harassment, its consequences and available penalties should be increased. For this to happen there is also a need to increase women's representation in TUs and improve direct representation of women's concerns. As workers associations they can encourage male and female workers to support women facing acts or threats of violence/ sexual harassment. They also have a role to play in encouraging workers to use workplace and local government/administration complaints mechanisms and monitor whether and how these mechanisms deal with cases in transparent and timely manner.

Finally, NGOs and bodies such as Shojag do have a role to play in coordination with the Government, BGMEA/employers and trade unions to address violence against women within the RMG sector. They have been working with the Ministry of Labour and Manpower, RMG employers and TUs to increase awareness of the prevalence of violence against women, in particular sexual harassment, its consequences for the individual and the workplace and also of mechanisms for prevention and redress. They may work with government agencies, employers and trade unions to develop capacity to address violence against women and sexual harassment. There is also a role in service provision, providing legal, health and psycho-social services or necessary referrals, to persons subjected to violence and sexual harassment. And finally they too can continue to increase awareness at community and national levels of forms and consequences of violence against women and sexual harassment.

Maheen Sultan, Member Naripokkho and Team Leader, Shojag Coalition. Contact email: [email protected]

*Shojag (Awaken) is a coalition consisting of five organisations, the Bangladesh Legal Aid and Services Trust (BLAST), the Human Rights and Legal Aid Services (HRLS) Programme of BRAC, Christian Aid, Naripokkho (in the lead), and SNV Netherlands Development Organisation. The Coalition, with support from Global Fund for Women, is implementing a project named An Initiative to End Gender-Based Violence (GBV) in the ready-made garments industry in collaboration with eight factories with which it has MOUs.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments