Who Made Frankenstein's Monster? Spoiler Alert: It's You

"I am malicious because I am miserable. Am I not shunned and hated by all mankind? Tell me why I should pity man more than he pities me? I will revenge my injuries; if I cannot inspire love, I will cause fear."

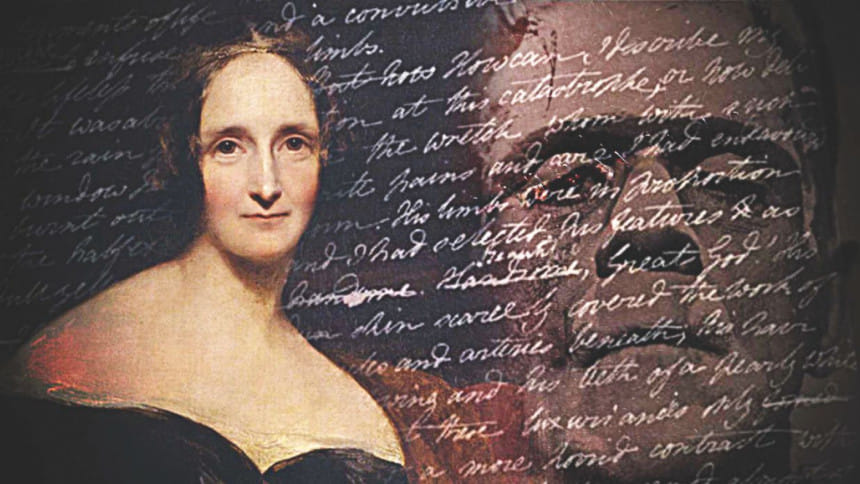

Mary Shelley's words—the monster's tirade—boomed in Professor KaisarHaq's voice as I entered the University of Liberal Arts (ULAB) auditorium on October 31, 2018. Head wrapped in a bloody bandage for ULAB's 'FRANKENREADS' Halloween celebrations, Professor Haq's reading of Frankenstein highlighted the rage felt by the 'monster' towards society. Abhorred and ostracised after being dragged into a warped existence by Victor Frankenstein, the creature was now ready to unleash his revenge on humankind.

It's not hard to guess why Professor Haq chose this passage for the 200th anniversary of the novel. The scene brings up some of the most crucial issues underpinning Shelley's text, such as the moral weight of scientific research and the responsibilities associated with creation. These questions have influenced a host of cross-disciplinary applications of the novel of late, encouraging, for instance, Stanford University to explore the ethics of stem cells, organ donation, and organ harvesting using the text in their classes. The scene and the novel overall are also pertinent in terms of how much we impose on nature in the process of urban and scientific advances. Just as Victor's creation and his refusal to answer for it trigger the deaths of his family and friends at the hands of the monster, victims of global warming today are similarly made to suffer for the actions of a privileged, irresponsible few. The monster's fury in the scene seems to encapsulate that of the planet itself, reminding us that the floods, cyclones, earthquakes, and train of natural disasters killing thousands every year are of our own doing; that the planet, injured almost beyond repair, has started to fight back.

That's one of the ways in which Frankenstein feels relevant today, I thought, as I watched ULAB celebrate 200 years of Frankenstein last week.

Another is the far more infamous cultural legacy of the novel, relating to the biggest myth surrounding Frankenstein. Most people who haven't read or watched Frankenstein know it to be the name of the monster. Few know that the creature wasn't even graced with a name in the novel. Its creator, scientist Victor Frankenstein, often refers to it as an "ogre", a "thing" and the "daemon" in the text. At one point, the creature tells Frankenstein that he ought to be called "thy Adam"; but the nickname doesn't seem to have stuck. Instead it became known as the 'creature': a fairly neutral label, and also a 'monster': a far more loaded one.

"To name is to pay attention; to name is to love," wrote Maria Popova in an article on the power of names for Brain Pickings. Victor Frankenstein felt no such love for his creation, and so conferred upon it no such dignity. Lacking a name, a proper place in human society, the creature thus induced horror in whoever he met through no fault of his own initially. In this absence of a name he acquired the identity of a "daemon", and so the causes behind his fury, the injustice dealt to him by Victor, vanished. A demon, after all, is evil because he simply is. This tale of evil was then told by Victor Frankenstein to Captain Robert Walton aboard a ship, who in turn repeated it to his sister in letters which form the epistolary form of Mary Shelley's novel. As a result, an unnamed being became immortalised as a villain. Word of mouth created a monster.

Meanwhile Victor, the one who had truly wreaked the havoc and then refused to own up to his actions, disappeared from public perception, until later readers created the platitude that "Knowledge is knowing that Frankenstein is not the monster. Wisdom is knowing that he is."

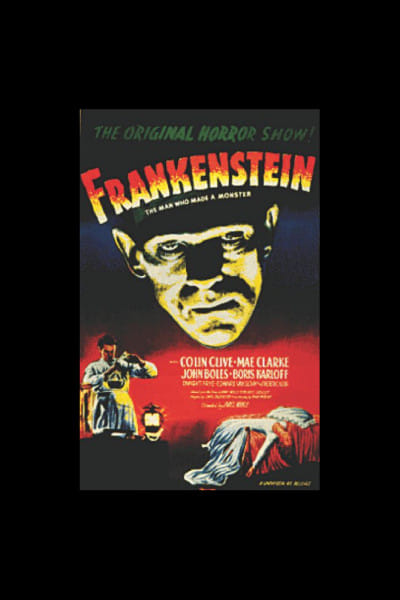

While the people within the novel helped paint the creature as this innately terrifying force, those outside it have helped perpetuate the myth. The misconception seems to have been born early—in 1838, just seven years after the novel was first revised for publication as a Bentley Standard novel, British Prime Minister William Gladstone referred to engineered hybrid mules as "Frankensteins of the animal creation". Years later, the poster for the 1931 film adaptation had the word "Frankenstein" printed alongside the face of the creature. From then to now, perhaps because of these mis-namings, Frankenstein's monster somehow became Frankenstein-the-monster, the towering mass of blue or green flesh with droopy eyes and outstretched arms featuring in horror spin-offs, children's cartoons and Halloween costumes.

Nine insane months after Victor first started making the creature, he lost control over it as it shot off into the world. Society—and his own irresponsibility—made it into something that Victor hadn't anticipated would exist. It grew from a being into a creature into the famed, feared monster. Mary Shelley's creation seems to have experienced a similar fate, growing from a nightmare seen by Mary in the stormy Swiss Alps to a ghost story for the ears of Lord Byron and Percy Bysshe Shelley into a novel that jump-started the genre of science fiction. Like the physical creation by Victor in the novel, Mary's literary character, too, crystallised as a monster at the hands of countless readers and non-readers. As it passes through time, through generations of audiences across the world, it is them—us—who keep the myth of the monster alive.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments