Words from a commoner

Tagore songs take me back to my childhood. They remind me of the nights when my mother would stay awake well past midnight to watch over me while I studied for my board exams. They remind me of the cold winter nights when my father would wrap me up in his shawl while watching TV. Rabindranath Tagore reminds me of a home that I have long forsaken for the sake of ambition and development.

As a child, the first Rabindra sangeet I learnt from my mother was the song 'Chaander hashi baad bhengeche'. To date, I have always wondered why my mother would choose such complex words and such a difficult tune as the first song to teach a four-year-old. I was learning not just the vocals, but also how to play the tune on the harmonium. Perhaps it was some kind of an episode that my mother (who was in her 20s) was going through at the time. Away from her homeland, a young mother of two—memories of a long-gone, carefree life do smother you from time to time. Growing up, we would listen to Rezwana Chowdhury Bannya rendering Tagore's tunes on weekends, right before going to sleep, and then wake up early in the morning to the melody of Indrani Sen's 'Tumi je shurer agin lagiye dile mor praane'.

There is a story that we heard as children about how and why Tagore wrote the song 'Aaj jochna raate shobai geche bone'.

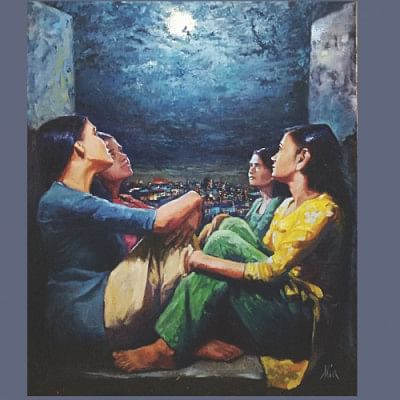

It had been a few days or weeks since Tagore's son had passed away. The ambience inside the ancestral home was slowly getting back to normal. The elders were still grieving, while the younger ones were getting used to their playmate no longer being with them. One night, the moon shone in all its glory—a purnima night. The younger members of the family begged the elders to let them go out to the forest to bask in the moonlight. Rabindranath himself was being coerced to accompany them. Tagore told them all to go ahead, promising to join later. While waiting in silence in his empty home, he could not but come to terms with the fact that his son had actually left him and everything else around him, and was truly never coming back. However, the moon still shone and nothing stopped the beautiful jochna from entering the thick forests around his home. He realised life always moved at its own pace and would never stop for anyone. Not only did this thought fill his heart with sorrow, but it also helped him come to terms with letting go. It was then that the beautiful words of "Aaj jochna raate shobai geche bone" was written in a little diary that he always kept with him.

I must have been very young when I heard the song. I don't remember when it became a part of my everyday existence. I would be found humming the tune during math problems, reciting the lines while standing in assembly, or simply playing the melody on the keys whenever I would find an opportunity to do so. I would even try to think of harmony lines for the chorus. Such has been my love for this particular Tagore number. I grew up listening to many versions of this song. While Indrani Sen's version started off with delicate sounds of the sitar in the beginning, Bannya's version had interludes played with string from the keys. The latter version became a huge hit at home, and many other Bengali homes for that matter all around the world.

However, in the late 2000s, Sahana Bajpaie and Arnob Chowdhury broke all rules and came up with an album called Notun Kore Pabo Bole. The whole idea behind this album was to recreate some of the age-old Tagore songs that we had grown up listening to, especially for young listeners. As expected, the album was a huge hit amongst young music lovers, and to date, the songs from this album are still a part of many a playlist here. The song "Aaj jochna rate" is to be given a special mention from this album even today, because of the heart-wrenching esraj that pierces the silence right before Sahana starts with her melody and words. The song not only broke all conventions when it came to instruments and pronunciations, but Sahana's cheerful style of throwing her voice re-defined this song for many. It became a beacon of hope and a sign to move forward and let go of the past.

I am happy to have grown up at a time when Bengali music, and Rabindra sangeet in particular, was listened to and practiced by ordinary Bengali families no matter where they lived. Those were the times when the compositions and the poet himself would be analysed and critiqued during addas over tea and meals amongst the elders. However, it is still a silver lining that Tagore is always a part of our lives, that the love for his poems and compositions seems to be increasing for many of us, who are forever looking for positivity and a little bit of hope for the people, the community, and for the country.

Elita Karim is a singer, writer, and Editor of the Arts and Entertainment section, The Daily Star.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments