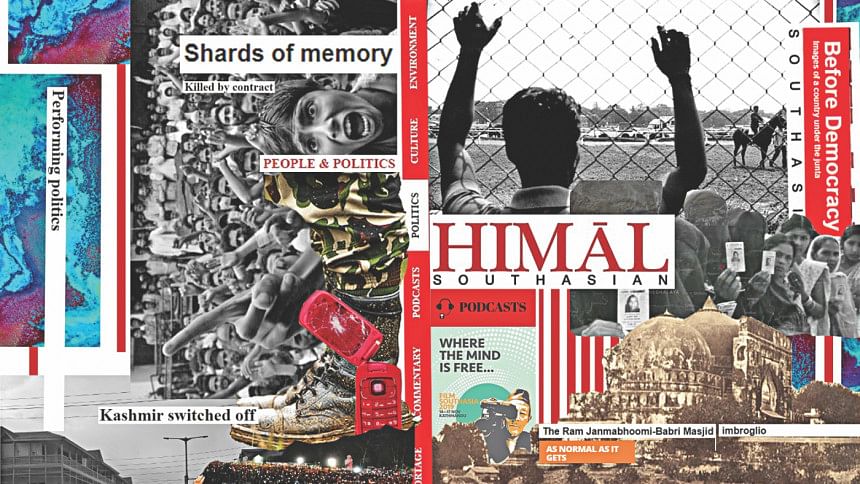

“The space for in-depth critical journalism is shrinking"

Why do you think independent publications like Himal Southasian are important in today’s media landscape?

I think independent media organisations are even more important today than ever before because most of mainstream media has almost completely ceded the space for journalism with a public purpose. Some years ago, we (Himal) published a volume called Growing Media, Shrinking Spaces and the title was deliberate. Despite the proliferation of media in our region, the space for in-depth critical journalism is shrinking, especially in mainstream media. While battles over censorship have been fought and won by many of these organisations, this new battle is being lost without a shot being fired because it is a battle of journalism against the commercialisation of media houses. Big media is subsidised by or has become vehicles for advertising revenue, and this in turn requires feel-good journalism. While critical articles are thrown in here and there as a sprinkling of credibility, really incisive journalism, the bigger questions of growing inequity and injustice are largely left unasked because such journalism does not go hand in hand with encouragement of rampant consumption which in turn drives the advertising revenue and the profit motive.

Tell us about the way Himal functions and is funded. How do you manage to survive at a time when even big media outlets are struggling financially and are having to slash their supplements and magazines?

Himal has always depended almost entirely on donor funding to subsidise its operations. Its model of cross-border, in-depth, public interest journalism was pioneering and received generous support from international donors for decades. However, that has changed in recent years and while we continue to receive support—currently from Open Society Foundations—it is becoming more of a struggle to secure donor funding. I must add here that despite the fact that “beggars can’t be choosers”, we beggars are quite choosy as well as careful about who we get funding from. We feel this is particularly important for a media organisation and this limits the pool of donors we are comfortable with.

There are many compelling claims on donor resources—and the urgency of equally or more compelling claims keeps increasing as governments across the region are retreating from their obligations to their citizens. Journalism is not always seen as an urgent, immediate need. Moreover, most donors in the media sphere are looking for the Next New Thing and increasingly seeking the magic mantra for sustainability. They are, therefore, keen to fund more experimental ventures. There are few takers for survivors and that’s what we are—we have stayed the course doggedly for over three decades.

All of this makes it imperative that organisations like ours find ways to reduce donor dependency. Non-profit should not mean non-revenue. We have experimented with several forms over the decades—the monthly magazine subscription format, the bookazine subscription cum book sales model, and now the online-only version for which we intend to launch the membership model. Given the fact that a substantive part of Himal’s readership is international, I think we have a really good chance of reducing our donor dependency in the short term and meeting most if not all our costs in the long term. But earning revenue requires a long runway of both time and investment and we have never had that. However, we intend to go as far as we can, for as long as we can, even with our limited resources. In the dire situation our region finds itself in today, there can be no excuses not to keep fighting for survival, even against the odds.

To extend upon this subject, Himal Southasian was forced to cease its operations in November 2016. The way in which bureaucratic measures were used to curb your freedom of expression is a warning for those wanting to set up independent media outlets or find alternative revenue models. Could you talk about what happened back then and how you went about the re-launch?

Governments everywhere are becoming more sophisticated. While the tools of censorship and overt attacks are still being used, new techniques are being minted which are simpler and yet more sophisticated. For example, investigations of some kind are initiated into an organisation. If this is to look into finances, no explanation or even smoking gun is required. Not only will the organisation find scant support—after all, who can vouch for another’s financial probity?—but it is usually the process which kills, not the outcome. The investigative process can be dragged out and there are no consequences for the government even if the organisation is found blameless at the end.

Moreover, many organisations pay scant attention to their admin and finance leaving them vulnerable, as loose ends can be used against them even where there is no malfeasance or intention of any wrongdoing. It is imperative that independent organisations, especially those critical of their governments, make sure their back-end is as impeccable as their work.

However, this is not always as easy as it seems. Rule of law is weak in most regions and the discretionary power of governments enormous. In the case of Himal, even though we had put in a lot of effort to ensure that we had strong transparent systems in place, we were shut down by bureaucratic strangulation. In our case, there was no investigation, no charge, and not even a single question about our financial and administrative processes. The government authorities simply withheld permissions on a host of issues until we were forced to close. Files were “held” for over a year. Result: Himal closed down. Consequences to government: nil. Yet we are one of the lucky ones. Being a regional organisation, we looked to see where we could relocate. We found a warm welcome in Sri Lanka—and a number of civil society leaders willing to become board members and offer practical advice on setting up a non-profit here. And though we felt it was unfair that our probity had not helped us survive in Kathmandu, that probity was necessary for us to relocate and set up here in Colombo.

I am quite convinced that Southasian solidarity is the only way forward as most of our region moves towards greater authoritarianism and increasing restrictions.

Has digitisation really democratised the media/can it even the playing field for independent media? Where do you think the challenges remain?

Digitisation is a tool and like any tool, its efficacy depends on how it is used. It has made it possible for organisations like us to continue publishing at a time when it has become harder to move hard copies across borders. It has allowed space for stories that could never be told earlier.

However, we also see the tools of digitisation being used to spread xenophobia and hatred. We see the challenge of “free” internet preventing organisations from earning a revenue, we see the flood of infotainment submerge serious journalism, we see algorithms short circuit our efforts to expand our knowledge, and ever-increasing simplifications drown out journalism that seeks to map an increasingly complex world.

How we do “regulate” fake news and social media platforms like Facebook without censorship and curtailing the right to free speech?

The comedian and actor Sacha Baron Cohen caused a stir recently when he said Facebook would have allowed Hitler to buy ads. I think there is a deep kernel of truth there that we are all missing. We have fought long and hard to make our print journalism more meaningful, we have paid the price for standing up to the onslaught of infotainment and against great challenges we have evolved standards, the red lines for what our newspapers will not advertise. Now in the name of new media, all those gains are being reversed. “Anything goes” seems to be the new mantra. We need to go back to the drawing board and remind ourselves of the standards that we evolved with great difficulty and move forward from there, not backward.

In terms of fake news—we need to pay considerably more attention. While we cannot pursue and debunk all fake news, I think we need to name and shame fake news at least when it appears in mainstream media. That would be a beginning. We are far more comfortable rewarding good journalism but somehow shy away from calling out bad journalism. Why can’t we, as journalists, be more openly critical of bad journalism the way we are critical of all other things?

Do you think the longform will survive the attention span of millennials and Gen Z?

I actually think the time for longform is not past but yet to come and this is why: all of us have hundreds or thousands of articles we bookmark but never get around to reading; we read dozens of articles on the same subject and they often leave us none the wiser. Eventually we will want to cut through that volume and read incisive pieces—we will choose quality because we can’t keep up with the quantity. We will look for articles that explain and increase our understanding instead of repeating what we have already read. That, precisely, will be long-form.

Especially for many of us in small independent media, the question we need to ask is: Do we want to add to the flood of similar sounding articles, or can we even compete with larger organisations which have the capacity of producing large volumes? Or are we going to make a decisive move away from that and focus on creating something where we can actually bring value that other larger profit-oriented organisations cannot? Even if it is hard going in current times, that is where we need to be when the shift takes place.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments