Do the masses really vote for fascism?

The elections are over, and India has spoken. Or so I hear. Modi will go on to rule for five more years, the country will systematically erase one history in favour of another. The BJP will methodically target minorities, hate crimes will go unpunished. The lives of cows will be worth more than those of Muslims and Dalits.

It all seems fantastical, but it’s been happening for years, a few hundred miles away. The signs, too, were there. If we’d looked, we might have seen the puppet masters at work.

In the months leading up to Modi’s victory, the Indian government stripped four million Muslims of citizenship in Assam, deported Rohingya refugees back to Myanmar, and fashioned state-wide disinformation campaigns to shore up support. It renamed cities with Muslim-sounding names, appointed priests with a long history of bigotry to leadership positions, and set up a committee to rewrite the history of India.

While the BJP went about its business, a crime was being committed against Dalits every 15 minutes. Muslims were being publicly lynched. Social media rumours were fuelling riots.

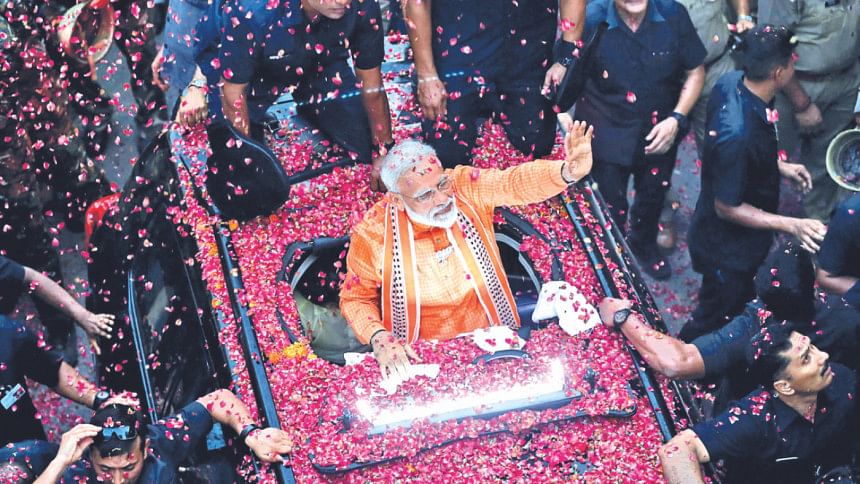

As the elections drew near, NaMo became the de-facto slogan of the BJP, a fond nickname for Narendra Modi. How ironic that namo exists as a word unto its own, how apt that in Sanskrit, it means ‘to bow’.

Should India have known?

The numbers indicate that minorities have been historically underserved in India. The worker-population ratio among Muslims in India is the lowest among all religious groups—ranging between 33 to 42 percent, and the illiteracy rate highest—22.3 percent compared to the national average of 17 percent. Lower castes don’t fare any better—they own the least land in India, have the highest unemployment rates, and the average Dalit woman lives 14 years less than the average non-Dalit woman.

And then there is Modi’s history. The riots in Gujarat that killed thousands when Modi was in charge. The endorsement of politicians convicted of inciting sectarian violence. His use of the RSS—the far-right group that wants an India of, and for, Hindus.

The news tells me India made a choice. The biggest democracy in the world chose a future for the many and damned the few. It’s easy to take that at face value. When elections have been won and lost, politicians share the spoils, the masses burden the blame. All that remains in the aftermath is a litany of blame and promises that can’t be kept. India will never be a country for one people, a diversity that survived the onslaught of two hundred years of oppression won’t capitulate to a goon. What will happen, what is happening, is the slow erosion of rights—first of those at the margins of society, then everyone else.

It’s easy to condemn those who voted for Modi. We can do that because we think ourselves impervious to hate. We don’t think the same could happen where we are.

But not too long ago, people marched in Dhaka and called for death to atheists. Right now, there are school textbooks that are teaching a contorted version of history to the next generation of voters. As I write this, there is fear that the Rohingya will radicalise, that refugees are taking up resources we simply don’t have. There are Shi’ite mosques that have been bombed and Hindu temples that have been desecrated. There are adivasis whose lands have been stolen, and activists who will never see the light of day. There are countless women who have been assaulted, there are minority children who have been raped.

Did we ever vote for that?

And then there is the world beyond. The U.S., where children find themselves apprehended at the border and put in cages; in Britain, where the ruling Conservative party has been rocked by allegations of Islamophobia. There is Brazil and Bolsenaro’s homophobia, China and Xi Jinping’s concentration camps, Myanmar and Suu Kyi’s genocide.

This is not an “India problem”—pretending it is, absolves us of responsibility.

When we condemn, we forget that fascism doesn’t appear out of ether, it slips in at the dead of night and organises our clutter. When we wake up, our choices have already been made for us.

Do the masses ever vote for that?

Imrul Islam works for The Bridge Initiative, a research project on Islamophobia in Washington, D.C. He is pursuing an MA in Conflict Resolution at Georgetown University.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments