An ethical documentation of the Birangona women

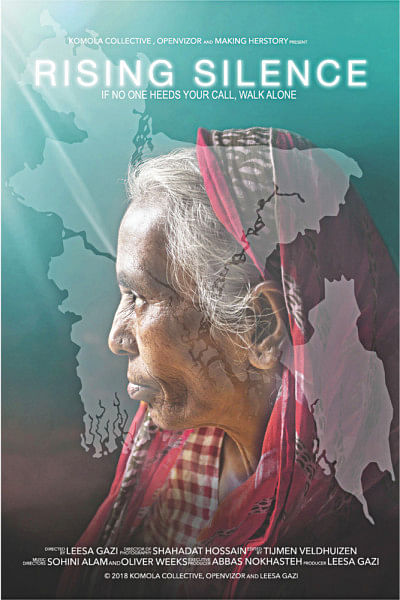

In the face of history’s death and patriarchy’s indomitable presence, Leesa Gazi’s Rising Silence comes as an undying beam—one that can stir the nation’s collective psyche and present the realities of “a forgotten genocide” before the current generation (and the ones to come).

According to estimations, around 200,000-400,000 women were tortured and raped by the Pakistani military and their collaborators during the Liberation War of Bangladesh. The numbers could be even higher. In a country where patriarchal norms are still revered, many think that talking about the war heroines (Birangonas), or even being one, is shameful. Many think that their roles were not as significant as the male freedom fighters. In the film Rising Silence, we are presented tough realities the Birangona women are having to live even today.

The film features, among others, three sisters who were tied up and ruthlessly beaten by villagers as others watched and laughed, right after the country’s liberation. As if the long days of suffering in the camps weren’t enough. Their fault? They were Birangona. They were deemed “impure”, “unclean”. Decrees marched to their doors to drive them away from their hearth and home. The event echoes the fact that in a country cupped in the palm of patriarchy, for the Birangona—the “brave women”—liberation brought very little.

Rightfully so, Rising Silence has recently bagged the Asian Media Award for Best Investigation (2019). The film unfurls before us the various complexities that have painted Birangonas’ lives through the women’s narrations and glimpses of their everyday lives. They speak of their ordeals in the camps, not in fragments, but in all its entirety.

Gazi also offers more than the testimony of women from just one village. She documents the narratives of indigenous women from the hill tracts and plain lands. And that documentation manages to overcome a certain singularity along the narratives and include those in the margins.

In every sense, as much as this documentation is brave and triumphant, it is also an ethically careful one as it deftly dodges the risk of blurring into the stereotypes that rule the public memory of the Birangona. Here, the women are more than their stereotypical portrayal as national wounds. Even though the trauma aches and hovers over them regularly, the women are steadfast on treading forward and “tell[ing] the world their stories”.

That Rising Silence handles the depiction particularly well can better be understood through the lens of Nayanika Mookherjee’s The Spectral Wound: Sexual Violence, Public Memories, and The Bangladesh War of 1971—a definitive work on the nuanced and ethical representation of Birangonas.

In her book, Mookherjee repeatedly emphasises how problematic it is to use Birangonas as props for earning one’s way into the high spheres of activism, to mark them in popular media as “wounds”, to create an identity of them as wretched, scared, veiled due to shame, their faces covered with long strands of hair. One striking example from the book would be the poster of a play by Komola Collective, a London-based theatre and arts group that works to promote women’s untold stories. For their play, Komola Collective took a popular image of a veiled Birangona woman who covers her face with her hands to express humiliation, and altered it. In the new version, “She holds up her fists in protest above her mouth while revolutionary women emerge out of the folds of her sari.” This is the same team that created Rising Silence, choosing long before the film’s release to challenge the stereotypes of Birangonas’ representation.

Mookherjee also highlights the usage of Birangona women’s past by those around them. She uses the term “combing”—which, among other implications, implies the digging up of their past and using it to taunt, insult, or quarrel with them. Combing manifests itself over a decent portion of the women’s lives portrayed in Rising Silence. One glaring example would be the three women getting beaten up by the villagers, described earlier. But other instances in the film include: a woman sharing, “If I go one way, they would go the other. Panjabi f***er, Razakar f***er, they would swear at us.” Another woman expresses how her son (a war child) has to endure bullying from his contemporaries, because he is “a residue” of the Pakistani soldiers.

The late Rajubala recalls how by-passers would threaten her and tease her often, mockingly bringing up her past. To them, she would reply, she is their mother. Without her, they wouldn’t be here. But it isn’t just spiteful villagers who hurl scornful remarks. Their children and other family members often do it too. Rajubala’s daughters were not proud of their mother’s sacrifice. Her in-laws refused to eat anything cooked by her. Only her husband stood by her, which is perhaps a rare glimpse of basic human decency showed by some of the Birangona women’s husbands.

After marrying a widower, another narrators’ life seemed to fall into place smoothly. But when her husband learned of her past (from an old villager), he beat her up badly (“He struck me with a brick and broke all my teeth”) and divorced her. Other narratives bare how many daughters hide their mothers’ identities as Birangona and how, despite that, their own marriages get broken up due to being related to a Birangona.

In Mookherjee’s terminology, “combing” also conveys both searching (for the Birangona’s wounds) and hiding them after certain activists are done interviewing the women for their work. Rising Silence avoids this by treating the women not as tragedies that need digging up to be shown on popular media, but by shedding light on their post-Liberation lives and their unflinching will. Leesa Gazi doesn’t just hastily touch upon these stories and drift away once they are taped. She shares intimate moments with the narrators. She walks with them clutching their hands. She chats, jokes, laughs, cooks, and spends days with them. In one scene, when Gazi asks the late Rajubala if she can sit beside her, the latter replies, “Why not? Aren’t you my daughter?”

By capturing the intricacies of the narrators’ lives in a way that grants them agency, and by documenting the women in a non-stereotypical, non-singular light, Rising Silence accomplishes a careful task, an ethical one. The film is a testament to the fact that misogyny and patriarchy intertwined with superstitions can cease to recognise a woman as a human being, especially when she is a victim of circumstances. These roots are unfortunately still alive in our country after 48 years of independence.

Shah Tazrian Ashrafi can be reached at [email protected].

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments