Fossil fuels spark wars and create migrants. Are renewables better?

There is a concept called the Resource Curse. Countries with high quantities of natural resources such as oil and certain minerals have poorer outcomes in democracy, stability and development. The wealth generated by these resources encourages economies of violent extraction, where profits go to the big men on top and their cronies, with little expended towards infrastructure or benefits for the masses. Democracy is stifled to prevent resource wealth falling into other peoples’ hands, and resource-cursed countries are plagued by conflict for the control of said wealth.

It is a neat little theory that diagnoses countries with sicknesses due to internal causes, geography creating inescapable destinies. A certain class of geopolitician and conflict scholars is enamoured with such narratives, where the very shape and nature of the soil and what it contains locks a nation into an expected script. It makes earning a living through punditry much easier.

A focus on naturalistic, internal causes ignores the role of foreign intervention.

Mineral-rich central Africa is destabilised because of the resource curse, and various domestic groups vying for their share of the pie. If there is talk of foreign presence, it is generally in the form of Islamic militant groups like ISIS or Al-Qaeda. The banditry of the Belgian Congo is absent from this story. Colonialism’s role in creating unstable, ill-equipped states is ignored, and when acknowledged, treated as a thing of the past. Neocolonialism—through, for example, France owning half of the foreign currency reserves of its former colonies and being legally entitled to give its companies first pick of investment opportunities and access to strategic materials such as oil and uranium—is rarely part of the picture. Foreign states and companies’ greed for African resources are not part of the destabilising equation; the inevitability of the resource curse excuses and obscures the role of foreign predators. We are left to conclude that Africans are the problem. Africans are simply overburdened with wealth and as such they cannot construct a functioning state; the wars and violence they produce refugees are their own fault.

No wonder Europeans are surprised and annoyed that refugees and migrants from Africa are seeking a life in their countries. Sure, once upon a time they may have done bad things (and most European citizens are ignorant of their own states’ colonialism), but that was well in the past—as postcolonial infrastructure and bindings are rarely discussed in the global media. They aren’t even involved in any wars down there, that the public is aware of.

The resource curse narrative encompasses North Africa and the Middle East as well. The seemingly intractable civil wars in Libya and Syria and, until recently, the threat of ISIS in Iraq can be seen as a dog-eat-dog competition for oil wealth. The resultant refugee crises are as such explainable by a combination of brown peoples’ greed, lack of discipline and tribalism. The military interventions by the West that deposed stable states are steadily forgotten.

Oil is a curse; the West just can’t help wanting it.

The greed for the petrodollar has caused untold devastation. The destabilisation of Iraq and Libya within the past two decades has chain-reacted into a much less secure world, creating circumstances that millions have been forced to flee from. As the United States has recently brought us to the brink of a third such major war with its sabre-rattling with Iran at the behest of the oil interests of Saudi Arabia, we have to wonder at the murderous capacity of the fossil fuel industry, which is not merely content with annihilating our children’s chances of living without skin cancer but is hell-bent on destroying our society in the present as well. The wars in North Africa and the Middle East, big and small alike, have created the current narrative of the refugee crisis, wherein those countries that have done the most to profit from the energy wars have been slow in their aid and quick in their demonisation. To add to this, we must also consider the callous displacement of indigenous communities in the United States and Canada in the pursuit of local fossil fuels.

This slow, ongoing cultural genocide is little discussed. You will hardly find any scholars applying resource curse logic to North America’s violence against its indigenous populations, or the rentier states they are devolving into as the interests of the oil and mineral industry capture the government through lobbying. These same energy resource companies join in the plunder of the wealth of Africa, Asia and Latin America, producing migrants who are demonised as unwilling to work to build up their countries, too lazy for the task, just as they are too lazy to develop their economies and states instead of seeking the instant gratification of violent extraction. Even Western allies such as the Arab Gulf states are tarred with the same brush; their resource wealth makes them corrupt and indolent. They are not real economies, just coasting by on what nature has provided them.

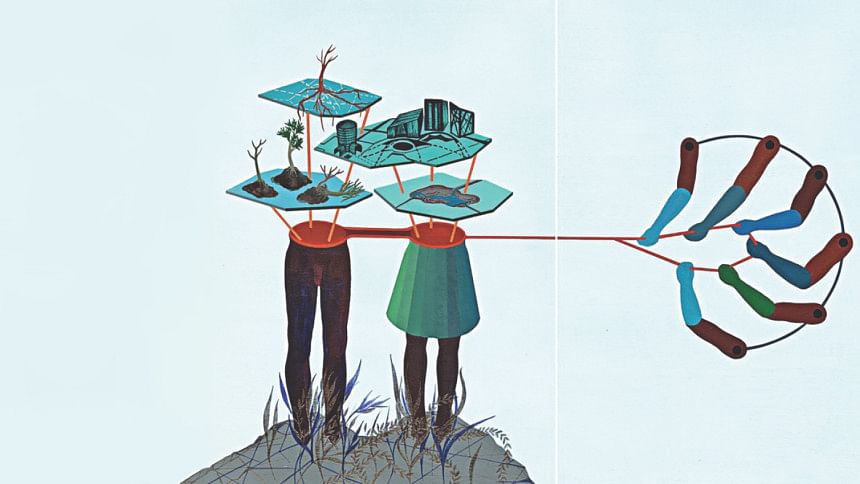

What can be done to destroy this neo-colonial cycle of external destabilisation of states and exploitation of resources, and the production and demonisation of migration? The answer appears to be to move steadily away from our dependency on resources whose profits encourage such violence. Fossil fuel dependency, moreover, is a prime contributor to the climate crisis through direct emissions and the wider transport infrastructure built around guzzling gas and petrol; energy capitalism will be responsible for climate migration on a scale hitherto unimaginable.

The solution is to switch our societies to clean energy. We, as a species, need wind turbines, wave energy converters, solar panels and those big holes in the ground that make steam using heat beneath the Earth’s crust, you know the ones. Yet even this is not a panacea in itself and must be approached with caution.

At Kaptai in 1962 the Pakistani government finished construction of a dam on the Karnaphuli River. A hydroelectric power plant was constructed, the only one of its kind in Bangladesh. At 230MW a year, Kaptai represents a small but crucial chunk of energy output in a country whose supply of electricity can hardly keep up with its growing appetite.

Bangladesh’s economy is a ticking time bomb for the environment, potentially just as devastating as China and India were when they came into their own. Despite Bangladesh’s gas wealth, it makes sense to look into cleaner energy solutions to reduce our country’s future carbon footprint.

Kaptai Dam was an environmental and socio-political disaster. The dam’s reservoir, Kaptai Lake, filled up an area that covered 40 percent of the local arable land and displaced 100,000 people. Tens of thousands of environmentally displaced persons crossed the border to India. Entire communities—primarily Chakma and Hajong—were uprooted with no possibility of return, their cultures and ways of living permanently altered, their futures uncertain. This outrage against a politically excluded group has spiralled out into the current state of unrest between Bengali settlers and paharis in the Hill Tracts. A conflict ultimately attributable to the colonial era’s map-drawing, but perpetuated by hydropower.

It was an insane price to pay for 230MW a year.

Is this clean energy? Are water and height the resources the hill tracts have been ‘cursed’ with? The cartoon villainy of the global fossil fuel industry masks such outrages, just as terrible, committed in the name of renewable energy. If we move away from oil and gas, we can’t be blinded by the halos worn by their replacements. At the very least, we should probably never build another dam again.

Zoheb Mashiur is an artist and an MA candidate in International Migration at the University of Kent. Read more of this sort of thing in Disconnect: Collected Short Fiction.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments