Ghartera Edition 0: Junkyard

“Unlearning is a long process”. It’s doubtful to me that if we were to assemble an ensemble of artists, curators, gallerists, collectors and everyone else who is engaged in the often self-valorising art circuits in Dhaka, that there would be many present who would have uttered the above statement on the eve of their exhibit’s closing. To be sure, this is not meant as a slight or a claim to a moral high-ground (using the term ‘art circuits’ automatically invalidates such pronouncements, anyway). It’s only usual to expect that an exhibition, or any other display of art for that matter, necessitates a parting message that speaks of a ‘learning’ rather than an ‘unlearning’. After all, many months of meticulous planning, frantic coordination and somewhat frazzled nerves demands a kind of fulfilment that has come from the entire process. What has this experience taught us? What have we felt looking at the objects/subjects under the sanitised white glare of the all-encompassing gallery?

Art spaces and institutions that ascribe to the culturally consecrated practice of maintaining glaringly white, untouched displaying surfaces, have often found themselves at odds with housing art that is altogether jarring and fractured in its existence. At the end of the day, the emptiness of the white space demands meaning from the art and the artist, and compels them to state a coherent, cognizable and appropriately cryptic raison d’etres which can fill the overpowering sense of emptiness. And so I return to my first statement—it is unusual for an exhibition to end on a non-ending, on an acknowledgement of the many skins it has shed from its body and of the many more that are yet to be discarded. But that is exactly how the organisers of Ghartera chose to end what they are calling Edition 0: Junkyard.

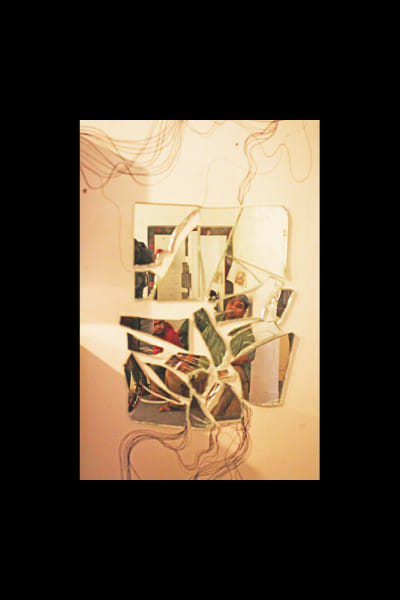

Much needs to be said regarding the unique circumstances under which this project began its journey and the curious way in which it came together in Gallery Dwip, at the bend of a Lalmatia alleyway. Perhaps much more than is possible in this writing. What can be said here, though, is that it is as ad-hoc and un-institutionalised as its name suggests. Being labelled Ghartera is to be marked out as deviant, as stubbornly rebellious, often in the face of overwhelming logic, and, as inherently disposable. The aptly titled edition, Junkyard, brought together a commune of artists and art works indulging in displays of the macabre, the unspeakable and the indecently queer, from which civility averts its gaze. The ensemble of artists themselves represented a smattering of rising, young practitioners, enthusiasts and new entrants into the world of fine arts and its many rituals. Emboldened by the concept of disposability, they chose to meditate on the slow decay of memories and the environment, the chimerical possibilities of the human form, the dissociation we experience as dwellers of this city. But above all, they brought with them works that were deeply political, inherently flawed and searing in their unashamed gaze at those who would come to visit.

In the process of bringing this exhibit together, the organisers themselves adopted their self-fulfilling tag of Ghartera. In a time of institutional hegemony over art and art funding, the exhibition went ahead completely self-funded, with a miniscule amount being raised via crowd funding. For this Herculean effort alone, the curator Kazi Tahsin Agaz Apurbo, deserves enormous credit. By his own admission, the materials used for propping up the artworks were themselves fashioned out of disposed items and low-budget back-end padding. The artists themselves put up funds to exhibit their work. The space itself was a brave pro bono provision on behalf of the ownership at Gallery Dwip. I say brave because in facilitating a space to curate the diverse body of unsettled and unsettling compositions, Dwip also tacitly placed a bold statement in front of the celebrated galleries, their gallerists and their curators—not only can a gallery survive beyond the self-circulatory pressures of funding crunches, it can thrive in surroundings where art-gallery decorum is replaced in favour of a tactile and malleable configuration of space.

For if you were to walk into the gallery, you had no choice but to touch. The displays of art demanded for you to hold the parchment, or fish out photos from inside a pouch, or to walk into the toilet unsure whether it was for use, or part of a display, or both. This was perhaps the biggest achievement for Ghartera and its organisers. They transformed a space into a living, breathing appendage of imagery, objects and words. And that the space allowed it, and welcomed it, meant that it shed the art-circuit elitism that is embedded into exhibitions, which automatically puts them beyond the access of certain bodies and not others. But since old toilet roll holders, plastic curtains and empty bottles of local alcohol (holding together at times sophisticated, at times mediocre, artwork) were given space to mark the imperfect and yet entirely unashamed landscape of the gallery, it meant also that it engendered access for the enquiring murubbi and the inquisitive child who sells toys on the adjacent street corner. Bodies, that would otherwise have wilted in the immaculately clean surroundings of the quintessential art gallery, could exist and engage here. Simply in terms of being a space for divergent and deviant bodies, Tasher Desh curated by Atish Saha and displayed in an old garments’ manufacturing factory is the only other exhibit that springs to mind. Although, unlike Tasher Desh, the artists were neither socially validated nor established.

In principal, Ghartera attempts to speak, more than it tries to show. The drawbacks of their discursive eloquence was evident throughout the duration of the exhibition. They spoke of too much, too soon and sometimes made the mistake of falling into patterns of resistance and anti-ness that some of the works had long left behind. Juxta-Beauty by Inan Anjum Sibun, City Subconscious by Ananda Antahleen and Ata Mojlish’s Traitor Memories were standout parts of the exhibit. They displayed a vision and a finesse that remains missing even in the works of establishment artists. That being said, a number of the displays were either too insistent on making their mark or bore the hallmarks of superficial solemnity, almost as if they remained unconvinced by their own thoughts.

But there lies the beginning of their end. “Unlearning is a long process”. Ghartera never claimed perfection, nor did it yet claim conviction over its own various resistances. It did, instead, demand the space to be disposable, to be imperfect and to be riddled with mistakes that many would much rather not let blemish the hallowed halls of an art gallery. It did that. It made a space where children of cities-long-declared-dead could step out of the existential hopelessness that floats up from the cracks in our concrete floors, and mould this feeling into seething anger. Anger that is political, that is sincere and that is, invariably, flawed.

Ghartera should thus be viewed as a journey, an initiation into a new kind of establishment. One that still retains its ability to smell of last minute varnish and cindered carpets and yet still demands attention. In ‘unlearning’ itself and forcing those in the space to ‘unlearn’ with it, the exhibit became more than just the sum of its junkyard parts. The entire collaboration engaged artists, art critics, art lovers, children, gallerists, curators, single mothers and aspiring artists in a way that had never before been thought possible in our ‘art-circuits’. On a personal level, Ghartera forced me to unlearn the ‘art gallery’, and made me feel optimistic about a long overdue movement that can reshape how art is understood, how art is displayed, and how art can one day look the state in the eye and make it wince. Long may the unlearning continue.

Ahmad Ibrahim is an independent researcher and writer.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments